Fascinating Characters: The Art of Writing and Text Cultures in East Asia

In the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Asian Art Museum) in Berlin, there is a small exhibition space at the intersection of the galleries for the arts from China, Korea, and Japan. It measures only about 200 square metres but is crucial for the new display of the East Asian art collections. Deliberately located, this Transregional Thematic Exhibition Gallery offers possibilities for shows that refer to all cultures of East Asia. These may be arranged in different combinations: pointing at the region as a whole, focusing on selected aspects, or highlighting only a certain area, genre, or theme. Furthermore, the exhibitions can address historical as well as contemporary topics; textual references to neighbouring displays will be possible.

The significance and relevance of the art of writing compellingly lends this subject to the opening presentation in this gallery (Fig. 1). Calligraphy is omnipresent in East Asia, where writing systems are crucial. They influence the arts and everyday cultures as well as the living environment and the thinking of the people. Chinese characters not only are a means of communication but also create identity, and they have become a medium of artistic expression in the long course of their history. Calligraphy, with its unique symbiosis of formal aesthetics and semantic meaning, forms an independent art genre across the region.

Still today, the art of writing is one of the most highly appreciated art forms. Written characters are an integral part not only of calligraphic works of art; texts form a key component of paintings and of pictorial representations in other media too. Inscriptions on ancient bronzes stimulated scholars’ interest in collecting these objects. Characters are part of the ornamentation of porcelains, textiles, and other decorative-art objects. Finally yet importantly, written characters appear wherever artworks are sealed or marked. East Asian calligraphy seems to be globally fascinating, attracting the attention of people who are not able to read the characters, in other parts of the world.

Fig. 1 Installation view of the exhibition ‘The Art of Writing and Text Cultures in East Asia: Fascinating Characters’, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, featuring: Jeong Hakgyo, two hanging scrolls; Xu Bing, Book from the Sky; Typographia Sinica; Chen Guangwu, Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion; Wang Dongling, Spring Night in Luoyang, I Hear the Flute; Yi Bingshou, couplet in clerical script; Zeng Mi, Old Man, Old Tree, Old Cabin

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph:

David von Becker

Fig. 2 Installation view of the exhibition ‘The Art of Writing and Text Cultures in East Asia: Fascinating Characters’, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, featuring: Chen Guangwu, Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion; Gu Gan, Drinking Alone Under the Moon; and banners with photographs of cityscapes

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph: David von Becker

The presence of characters in public spaces throughout East Asia has been increasing over the past centuries. Characters are ubiquitously present everyday, especially in urban environments. The exhibition at the Asian Art Museum presents this aspect of the theme with five banners with photos of cityscapes from Tokyo, Seoul, Taipei, Hong Kong, and Beijing, integrated into the show’s design (Fig. 2). With the digitization of media, access to this character system and its use is changing rapidly. In light of this, the works by numerous modern and contemporary artists address multiple facets of the writing systems.

To differentiate the thematic exhibition from the surrounding ones, the gallery’s didactic texts are distinctively designed, inspired by the colour and form of the red seals on works of calligraphy and painting. The limited selection of fifteen objects provides a glimpse into the multiple aspects of the subject matter, and it focuses on the recent past and the present. Works by contemporary artists from China and Japan were collected during the first decades of the East Asian Art Collection (Ostasiatische Kunstsammlung), which was founded in 1906 and was one of the forerunners of the Asian Art Museum. Today, contemporary art is among the focal points of the museum’s acquisition activities. Even if the scope and diversity of modern and contemporary art production can never be reflected in a museum, a selection of works can give visitors a sense of the complexity of the vivid art scenes and art currents in Asia. Moreover, essential features of traditional cultures continue into the present. While their influence may be more or less obvious, they definitely form a conceptual substrate of newer works. The reflection of traditional cultures in works of contemporary art can facilitate viewers’ access to visual phenomena and cultural codes that may be unfamiliar to people who are outside the respective cultures.

The prelude to the exhibition establishes a link to the history of the Berlin Palace, where the Asian Art Museum is housed, and to the beginnings of Sinological research in Berlin. The Typographia Sinica, a collection cabinet with ten drawers containing a total of 3,287 Chinese printing types, is a loan from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library) and forms part of a semi-permanent exhibition of the Humboldt Forum, featuring 35 historical objects distributed throughout the building (Fig. 3). (Regarding the history of the cabinet, see Gumbrecht and Fischer, 2019, pp. 66–77.) The cabinet’s origin is connected to the Berlin provost and polyglot linguist, Andreas Müller (1630–94), who had access to the Chinese collection of the library of the Brandenburg elector, Friedrich Wilhelm (1620–88), founded in 1661. Müller’s knowledge of Chinese made him famous throughout Europe. He conducted research to invent a key that would serve to make Chinese characters easily accessible and translatable into any other language. While his efforts were not successful, they perhaps resulted in the Typographia Sinica, which is probably the first attempt to produce a basic set of Chinese characters in Europe. The cabinet is not only of historical interest but also an early cultural appropriation, testifying a Western fascination for Chinese characters.

Fig. 3 Typographia Sinica, cabinet from the electoral library in the Berlin Palace containing 3,287 Chinese printing types

By Andreas Müller (1630–95); c. 1680

Oak and pear wood; 103.4 x 109.6 x 60.5 cm

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, East Asia Department (Inv. No. Libri sin. 19)

Image © Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph: Jester Blank GbR

Apart from this object, the exhibition was planned to feature solely objects from the museum collection. However, the Korean collection of the Asian Art Museum is not large and only partially suitable for illustrating the key position of Korean art in East Asia; it unfortunately does not contain a single calligraphic work. (A brief history of the museum’s Korean collection is included in Korea Rediscovered! Treasures from German Museums, 2011.) The museum is therefore extremely grateful for the active support by the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, which made it possible to borrow three works of art from that museum and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art for the duration of the exhibition.

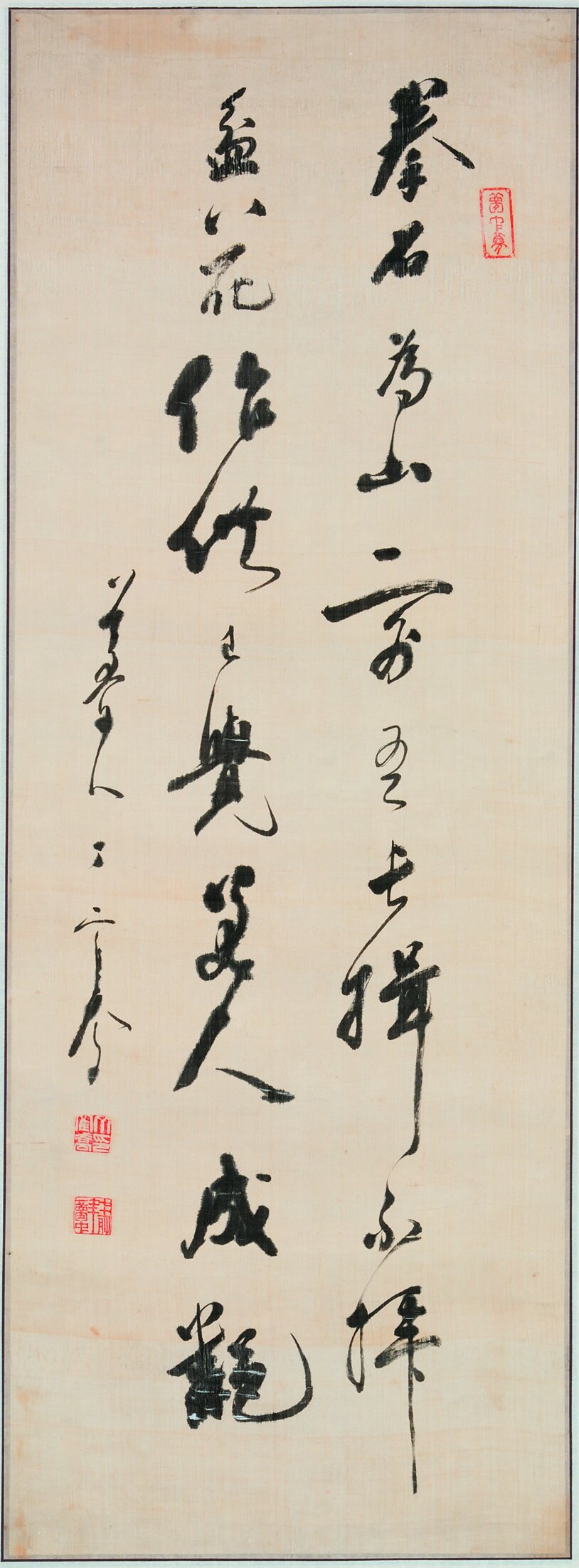

Two hanging scrolls by Jeong Hakgyo (1832–1914), labelled as a pair by the lending institution, illustrate the close bonds in the fields of philosophical and artistic concepts between Chinese and Korean scholars at the end of the 19th century (Figs 4a–b). Scholars shared interests in old inscriptions and oddly shaped stones, among others. The contrasting and varied lines of Jeong’s work indeed make one think of bizarrely formed scholar stones. One of the poems refers to the Song-dynasty (960–1279) scholar Mi Fu (1051–1107) and his passion for stones; the other poem celebrates inspiration fostered by drinking wine while immersing oneself in nature.

The use of the Korean alphabet (hangeul) is the most striking feature of the two other loans, Songs of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers (1988) by Kim Chunghyun (1921–2006), and Climb High and Look Far Ahead (1978) by Seo Heehwan (1934–95). These more recent works prove the striving of Korean artists in the second half of the 20th century for independent positions that navigate and emphasize national and cultural identity. Kim Chunghyun’s work is a calligraphic reinterpretation of an excerpt from a 15th century woodblock print describing the moment of Buddha Shakyamuni’s birth (Fig. 5). The original print is credited as one of the earliest historical documents written in hangeul. Most significantly, it dates from the time of the King Sejong (1397–1450) who completed the invention of hangeul in 1443. Sejong compiled the Songs of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers (Worin Cheongangjigok) in honour of his late queen, Soheon (1395–1446).

Figs 4a–b Two hanging scrolls with poems

By Jeong Hakgyo (1832–1914); Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), c. 1900

Ink on silk; 97 x 38.7 cm, each

National Museum of Korea, Seoul (Inv. No. bon 8228)

Image © National Museum of Korea

The optimistic, defiant tone of Seo Heehwan’s poem can also be interpreted patriotically. The two four-syllable lines of the title are inscribed at the centre of the composition, thus creating the illusion of a couplet. The artist refers to a classical format and at the same time creates the impression of a modern and experimental design.

A wonderful enrichment of the museum’s collection is the work The Moment of Memory (Sweat, Heart, Bread) by the artist Choi Jeong Hwa (b. 1961), which was acquired recently (Fig. 6). Everyday life and trash culture inspire the artist’s installations. Here, Choi applied words in neon letters to discarded consumer objects that address fundamental aspects or needs of life, to visualize the moment when past and present come together. The words chosen are simple: they read ‘sweat’, ‘heart’, and ‘bread’. This three-dimensional calligraphy was also preceded by an act of writing on paper. Taking on sculptural forms, the letters are, in the artist’s words, ‘like blossoms or sprouts springing from old objects’. The work is ideally suited for the show, bringing together concepts of everyday design as well as popular and urban culture.

In the exhibition, Japanese calligraphy is represented by two impressive works. A four-panel piece by Morita Shiryū (1912–98) transcends the border between calligraphy and decorative art. Four large ochre-orange characters reading ‘gardens of music’, written with aluminium bronze, appear on a black Japanese lacquer background (Fig. 7). The dynamic brushwork of the cursive script lends a plastic effect to the four characters. The work was originally shown at the spherical concert hall of the German Pavilion at the 1970 world’s fair in Osaka, Expo ’70, where works of contemporary music by Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) and other composers were performed. The subtly varied formats of the four individual panels suggest a rhythm and emphasize the musical component of the script. Hung on the side of a new tea house designed by the architect Jun Ura, the panels enter into a dialogue with the black lacquer surfaces integrated there.

Fig. 5 Song of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers

By Kim Chunghyun (1921–2006); 1988

Ink on paper; 131.7 x 68.7 cm

National Museum of Korea, Seoul (Inv. No. jng 9196)

Image © National Museum of Korea

Fig. 6 The Moment of Memory (Sweat, Heart, Bread)

By Choi Jeong Hwa (b. 1961); 2020

Neon letters on discarded household objects; Sweat 53 x 47 x 28 cm, Heart diameter 35 cm, Bread diameter 52 cm

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; acquired from the artist ( Inv. No. 2021-12)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph: David von Becker

On the opposite side, a monumental character that reads gō (‘impressive’ or ‘great’) dominates the wall. The character of almost two metres height was executed by the outstanding representative of Japanese avant-garde calligraphy, Inoue Yūichi (1916–85) (Fig. 8). In his works, the artist explored the potential for performance that is inherent in the genre of calligraphy and translated it into a contemporary language.

The collection of calligraphy at the Asian Art Museum is strongest in the area of China. The earliest of the exhibited works dates to 1811 and was written by Yi Bingshou (1754–1815), an important representative of the Qing-period (1644–1911) stelae school of calligraphy (Fig. 9). Yi’s huge couplet with large characters in clerical script enters into dialogue with the work by the Korean calligrapher Jeong Hakgyo, presented opposite. Both artists shared an interest in antiquarianism and studied ancient stelae inscriptions, and they represent numerous transcultural references within East Asia. Yi Bingshou emphasized the generally auspicious character of couplets in his work by using a beautiful printed painting ground, featuring bats and clouds in gold lines.

The work Old Man, Old Tree, Old Cabin by Zeng Mi (b. 1935) is not a work of calligraphy in the strict sense but rather a painting integrating a long inscription (Fig. 10). In the exhibition, it serves as an example of the essential significance that quotations, literary references, and references to canonical artists generally occupy in East Asian painting and calligraphy. Zeng Mi is one of the most interesting representatives of New Literati Painting, a movement that at the end of the 20th century aspired to revive the spirit of classical education and self-cultivation. In his painting, he included a lengthy quotation from the essay collection Clandestine Jottings from My Little Window (Xiaochuang youji) by Chen Jiru (1558–1639). Zeng Mi appropriates the writings of the eminent scholar, art connoisseur, and theorist to reveal deeply personal life experiences. The painting, which refers to a traditional theme—the scholar in his reclusive retreat in the midst of a mountain landscape—can be seen as a key work of the artist, a self-portrait that arose out of self-exploration in comparison to a classical role model. In exemplary manner, the work furthermore represents the unity of the Four Perfections (si jue), the arts of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving.

Fig. 7 Gardens of Music

By Morita Shiryū (1912–98); Shōwa 45 (1970)

Four lacquered panels; (a) 77.5 x 102.5 cm, (b) 75 x 102.5 cm, (c) 69 x 96.5 cm, (d) 65 x 89.5 cm

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; donation Federal Minister of Economy and Finance, Bonn (1972-9 a, b, c, d)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph: David von Becker

Fig. 8 Character Gō

By Inoue Yūichi (1916–85); Shōwa 35 (1960)

Ink on paper; 181 x 249.5 cm

Loan from private collection (Inv. No. DLG 199-2001)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Photograph: Jörg von Bruchhausen

The work of Wang Dongling (b. 1945) also makes reference to an icon of classical poetry (Fig. 11). On a hanging scroll is a text he wrote in 1986 for a student from Germany, in which the artist cited the poem Spring Night in Luoyang, I Hear the Flute by the Tang-dynasty (618–907) poet Li Bai (Li Taibo, 701–762). Wang Dongling is one of the best-known Chinese calligraphers of the present day and contributed substantially to the modernization of the genre. Famous for his version of ‘wild cursive script’ (kuang cao), he also emphasized the genre’s qualities of performance. Regarding this point, the exhibition allows viewers to draw a parallel to the work of Inoue Yūichi.

Another popular poem by Li Bai, Drinking Alone Under the Moon, was applied by Gu Gan (1942–2020) in an extraordinary work, recently acquired thanks to generous support from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst (German Society for East Asian Art). In this work, six pine slats are reminiscent of bamboo strips that were writing surfaces before the use of silk and paper (see Fig. 1). The material is evidence of the artist’s creative and pragmatic approach during his residency in Germany, where he lived from 1987 to 1993. Gu Gan was also one of the driving forces of the calligraphy-modernization movement. In his work, the artist deconstructed and reassembled the elements of the characters, combined different writing styles, and experimented with colours. The pictorial and painterly elements of characters are playfully accentuated and can be experienced even by viewers unfamiliar with Chinese characters.

The more recent generation of artists continues to challenge the boundaries of materials and forms. The conceptual artist Chen Guangwu (b. 1967) creates interpretations of what he sees as a largely destroyed culture that has deformed its essential art-historical and historical themes to the point of disappearance. Rather than writing his version of the legendary masterpiece Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion with brush and ink on paper, Chen wrote it on 2,772 small wooden cubes and arranged them in the form of a large puzzle. (According to tradition, the original version of this key work of Chinese literati art was written by the iconic scholar Wang Xizhi [307–365] during a meeting with like-minded scholars on the third day of the third month in the year 353.) During the first presentation of the work, in the Alexander Ochs gallery in Berlin, visitors were invited to play with the cubes and to change their positions, resulting in an irreversible destruction of the original text, which became unreadable in places but simultaneously endowed with different meaning. In this way, the artist’s work creates a new image that takes up the claim to the universality of art and thus, despite its roots in Chinese culture, can be emotionally understood by Western viewers as well.

Fig. 9 Couplet in clerical script

By Yi Bingshou (1754–1815); Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 1811

Ink on paper with gold decoration; 347.4 x 71.3, each

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; formerly Mochan Shanzhuang collection, acquired 1988 with support of the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin (Inv. No. 1988-56 a, b)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Photograph: Jürgen Liepe

Fig. 10 Old Man, Old Tree, Old Cabin

By Zeng Mi (b. 1935); 1999

Ink on paper; 69 x 69.5 cm

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; donation of Dieter and Si Rosenkranz (Inv. No. 2006-5)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Photograph: Jürgen Liepe

Fig. 11 Spring Night in Luoyang, I Hear the Flute

By Wang Dongling (b. 1945); 1986

Ink on paper; 136 x 66 cm

Loan from Andreas Schmid, Berlin

Image © Andreas Schmid

One of the most renowned contemporary artists from China, Xu Bing (b. 1955), is generally interested in sign systems and topics of communication. Book from the Sky is one of the first works that established his international reputation. The set of four volumes in a box presented in the exhibition is just a part of an originally much larger installation (see Xu, n.d.). Between 1987 and 1991, Xu Bing carved more than 4,000 invented characters into wooden printing blocks. They all consist of the basic components of Chinese characters but were reassembled into fantasy forms. Thus, the texts printed from these blocks remain just as illegible for observers who know the Chinese language as they are for observers who do not. Every viewer becomes illiterate when confronting this supposedly authentic but artificially created and unreal cosmos of language and is encouraged to question conventional perceptions of language and culture.

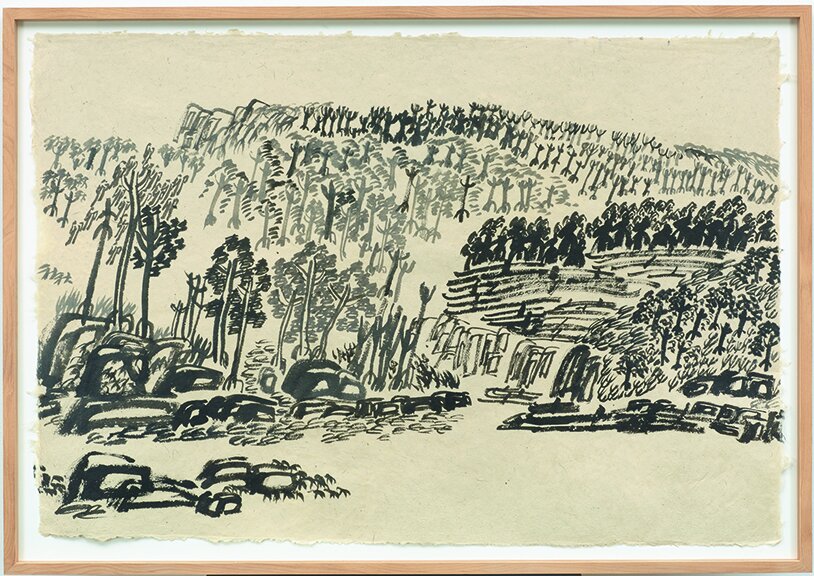

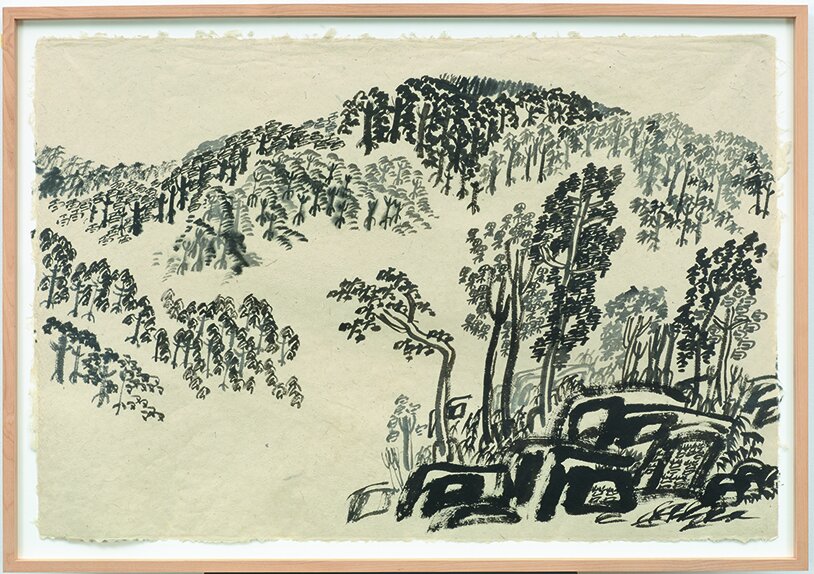

The representation of landscape with the help of Chinese characters also fits into Xu Bing’s wide-ranging interest in sign systems. Melding painting and calligraphy in an unexpected way, the artist created the five large-scale Landscripts for the exhibition ‘Xu Bing in Berlin: Language Spaces’, which was shown at this museum in 2004 (in cooperation with the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst and the American Academy in Berlin). The works depict a landscape made up almost entirely of Chinese characters (Figs 12a–e). The forest is shaped by characters for several types of trees or for forest; the mountains are composed of the characters for mountain, stone, and soil; doors and windows of a hut are formed by the characters for door and window, respectively; meadows in the landscape are similarly identified by characters for grass. The landscape is visually recognizable and can at the same time be read like a poem. Viewers are invited to imagine filling the areas of characters with individual memories. The image thus opens up a poetic dimension in which concepts and perceptions blend (Fig. 13).

Figs 12a–e Landscripts: Ten Thousand Trees

By Xu Bing (b. 1955); 2004

Five leaves of ink on paper; 115 x 185 cm, each

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; acquired 2004 from the artist with support of the Kulturstiftung der Länder, permanent loan of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst (Inv. No. DLG O-1271-2018)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Photograph: Jörg von Bruchhausen

One Hundred Women is the work of Jia (b. 1979), the only female artist represented in the exhibition (Fig. 14). At first glance, the work shows a well-arranged cosmos that conceals loss and ruptures behind it. In this work, Jia addresses the reform of written characters in the People’s Republic of China in 1955, which created simplifications accompanied by losses of meaning. Arranged on the canvas in a grid pattern are characters that symbolize this damage. All of them have the element for woman $k and a meaning related to ‘woman’. In this work, Jia applied a type style that was developed for the first printing presses but also used for propaganda posters. Through her creative process, the artist has distanced herself as far as possible from the guidelines of calligraphy, as the characters are made with stencils and acrylic paint.

The topic of this thematic exhibition is complex. However, the selected works of art can provide insight into the significance and affinities of calligraphy throughout East Asian cultures and demonstrate the relevance of the art form until the present day.

Fig. 13 Installation view of the exhibition ‘The Art of Writing and Text Cultures in East Asia: Fascinating Characters’, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, featuring, left to right: Xu Bing, Landscripts; Jia, One Hundred Women; vitrines with 20th century Chinese painting

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss / Photograph: David von Becker

Fig. 14 One Hundred Women

By Jia (b. 1979); 2016

Acrylic on canvas; 100 x 100 cm

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin; acquired from the artist (Inv. No. 2016-69)

Image © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst / Jia

Uta Rahman Steinert is the Curator for modern Chinese art and for Korean art at the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Selected bibliography

Korea Rediscovered! Treasures from German Museums, Seoul, 2011.

Cordula Gumbrecht and Christian Fischer, ‘Demnächst im Humboldt-Forum: Die “Typographia Sinica”’, Bibliotheksmagazin: Mitteilungen aus den Staatsbibliotheken in Berlin und München 40 (2019): 66–77.

Xu Bing, ‘Book from the Sky’, Xu Bing, http://www.xubing.com/en/work/details/206?classID=1&type=class

This article first featured in our March/ April 2022 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.