The Abstract Prints of Hagiwara Hideo

In 1954, the Japanese oil painter Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007) turned to woodblock printmaking after falling ill with tuberculosis. Right from the start his prints were abstract in style, which made his reputation abroad as well as in Japan. Throughout his printmaking career he was a constant innovator in his choice of motifs, style and technique, and his works have been collected by many major museums, including The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and The Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art and The Museum of Modern Art in the US. The Minneapolis Institute of Art, through recent, generous donations by the artist’s son Hagiwara Jo and collectors Gordon Brodfuehrer, and Sue Kimm and Seymour Grufferman, is home to what is arguably the largest collection of Hagiwara’s prints outside Japan and is currently presenting the first retrospective of his work, which showcases the artist’s enormous versatility.

Born in Kofu city, Yamanashi prefecture, in 1913, at the age of seven Hagiwara Hideo moved with his family to Korea, which had been annexed by Japan ten years earlier. His father had been appointed chief of police of Chongju city in North P’yongan province (in today’s North Korea), later moving to Kanggye city in Chagang province (also in North Korea) and eventually to Dandong in today’s Liaoning province, China (then part of Manchukuo, a puppet state of the empire of Japan in northeast China and Inner Mongolia from 1932 until 1945). Hagiwara, having returned alone to Japan in 1929, graduated from high school the following year and began to study oil painting with Mimino Usaburō (1891–1974). Originally from Osaka, Mimino had moved to Tokyo and graduated from the Oil Painting Department of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (known today as the Art Department of Tokyo University of the Arts) in 1916. From 1914, his paintings had been admitted to various annual exhibitions, such as the government-sponsored Bunten. His student, the talented young Hagiwara, succeeded in having his own paintings accepted in the annual exhibitions of the Hakujitsukai and Kofukai art associations at the early age of nineteen, as well as in an exhibition held by the Japanese Watercolour Painting Association (Nihon Suisai Gakai) the same year, to which he submitted a watercolour.

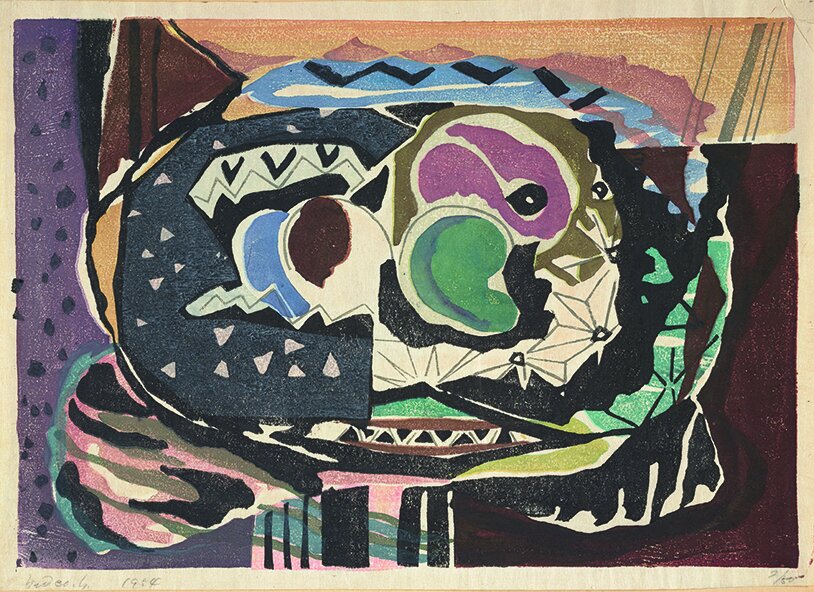

Fig. 1 Still Life with Peaches

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1954

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 26.9 × 37.5 cm

Gift of Mary Anette and David Thompson (89.120.11)

Fig. 2 Composition P

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1958

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 26 × 40 cm

Gift of Mary Anette and David Thompson (89.120.16)

In 1933, Hagiwara entered the Oil Painting Department of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, where his teacher Mimino had studied. Graduating in 1938, he joined the Takamizawa Woodcut Company (Takamizawa Mokuhansha), which specialized in producing reproductions of ukiyo-e prints by popular artists of the Edo period (1603–1868) like Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). Hagiwara worked not as an artist, however, but as a quality controller, whose task it was to compare the reproductions with the originals and if necessary, order corrections. Drafted in 1943 into the Eastern District Army, which was responsible for defending eastern Japan, Hagiwara lost his house, his atelier and most of his early works in the Tokyo air raids of 1945. He was finally able to build a new studio in 1950, and the following year, had his first solo exhibition of oil paintings at Shiseidō Gallery, in the Ginza district of Tokyo. However, he began to experience severe health issues shortly thereafter, and discovered he had contracted tuberculosis.

While some English texts claim that Hagiwara had attended a woodblock printmaking course by Hiratsuka Un’ichi (1895–1997), one of the leading figures in the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement (for example, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900–1975, Honolulu, 1995), this seems highly questionable since it is mentioned neither by Hagiwara himself in various interviews nor in Japanese research materials. In fact, it was not until December 1953, when Hagiwara entered a tuberculosis recuperation programme, that he learned woodblock printmaking and began to create his own prints. Among his early prints are several still lifes, such as Still Life with Peaches (Fig. 1), which relate strongly to Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) still lifes from the 1910s, the early period of the cubism avant-garde movement. In 1955, he created the series ‘20th Century’ (‘Nijū seiki’), echoing the work of Salvador Dali (1904–89). Yoseido Gallery in Tokyo’s Ginza district mounted Hagiwara’s first solo exhibition of woodblock prints in March 1956, and the following month, he was accepted to the annual exhibition of the prestigious Japan Print Association (Nihon Hanga Kyōkai). His large series ‘Composition’ (‘Konpojishon’), which followed in 1958 and for which he created one print for each letter of the alphabet, showcases his sense of innovation (Fig. 2). Fascinated by the texture of wood, Hagiwara created criss-cross patterns on the paper with inked pieces of driftwood to give the impression of relief. His prints were accepted to the first International Triennial of Coloured Graphic Prints in Grenchen, Switzerland, the same year, garnering him international recognition for the first time.

Fig. 3 Milky Way

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1959

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 42.9 × 33.3 cm

Gift of Sue Y. S. Kimm and Seymour Grufferman (2019.78.74)

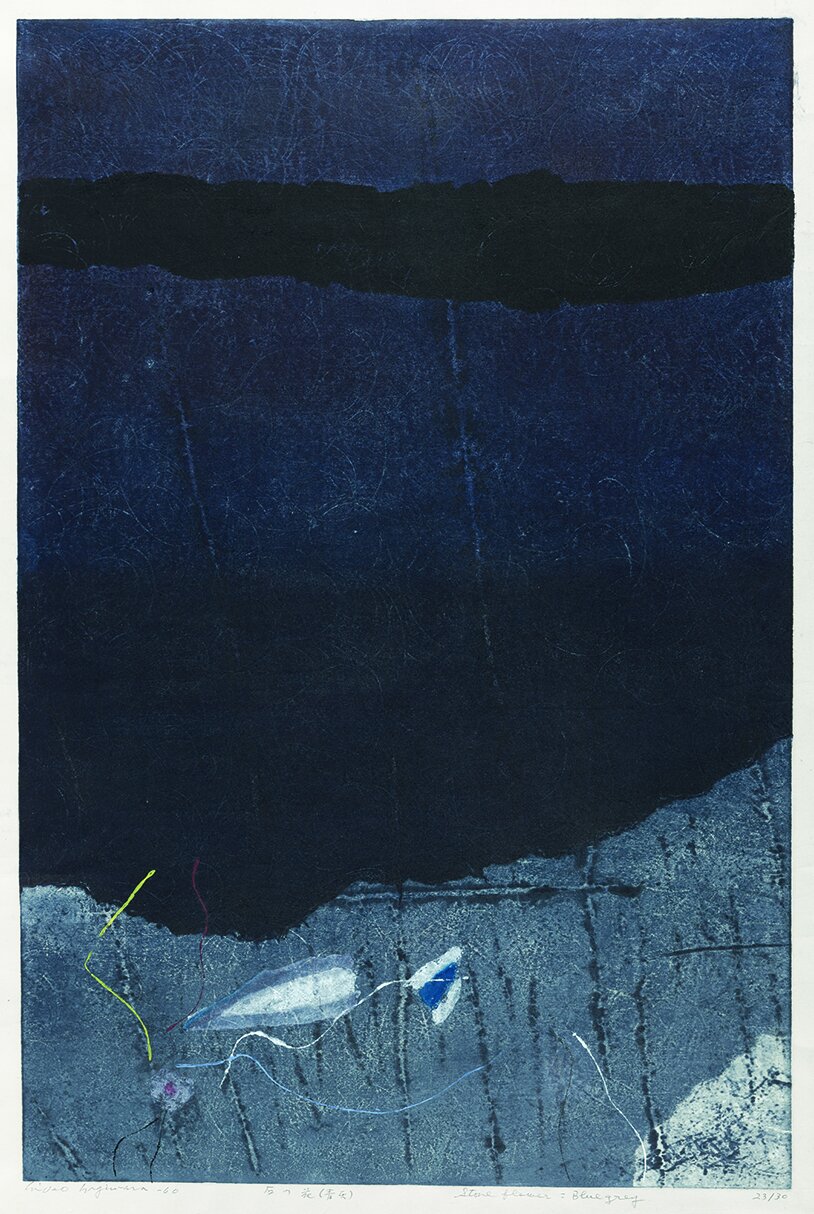

Fig. 4 Blue, Grey, from the series ‘Stone Flower’

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1960

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 99.1 × 66.8 cm

Gift of Sue Y. S. Kimm and Seymour Grufferman (2019.78.81)

In 1959, inspired by the effect produced by the colour bleeding through to the back of the paper in ukiyo-e prints, Hagiwara came up with the idea to print not just on one side of the paper, but on the reverse as well (ura-zuri). By forcing the pigment through the paper from the back as if dyeing it, he influenced the appearance of the printed design on the front—a technique that no other artist had experimented with before (Fig. 3). Among the first works that demonstrate this effect is his series ‘Memory of Snow’ (‘Yuki no kioku’), the second of the three different designs in which was illustrated in the arts section of Time magazine on 7 September 1959. He vehemently pursued this new technique in 1960, for example in the series ‘Soil’ (‘Dojō’), with twenty different designs; ‘Devil Flower’ (‘Aku no hana’), with five designs; and in the ‘Stone Flower’ (‘Ishi no hana’) series of seventeen designs, where he emphasized just one or two colours (Fig. 4). Regarding the latter series, he explained: ‘Thinking about eternal life, I gave the series the title “Stone Flower”. A living flower has a short lifespan, but the formation of a stone took thousands and thousands of years’ (Musashino shiritsu kichijoji bijutsukan, Hagiwara Hideo shozōhin zuroku, Musashino, 2007, p. 24; author’s translation). Since this novel technique of double-sided printing was very laborious and time-consuming, however, Hagiwara soon ceased to use it for all prints in a series. For example, not all the 26 prints in the ‘Man in Armour’ (‘Yoroeru hito’) series of 1962–63, which he created using abstract forms resembling the metal or leather of the breastplates of samurai armour, were printed on both sides. He would completely abandon the technique in 1965, using it to print only five of the sixteen prints in the series ‘Ancient Song’ (‘Kodai no uta’).

Next, Hagiwara invented special pads that scored the surface of the paper when rubbed across it to press the paper onto the inked woodblock, thus creating additional effects. His standard approach was not to begin with sketches, but instead to visualize a new idea and then employ a variety of tools to carve it directly into a plywood block, thereby producing a much more spontaneous work. Only occasionally did he turn to figurative subjects, for example in 1965 with the series ‘Greek Mythology’ (‘Girisha shinwa’). He had encountered the stories of the Greek gods, with their tales of vice and virtue, good and evil, in the 1950s. For Hagiwara, the ancient legends and the gods’ personas were a mirror of our world and exposed the truth about human nature. Each print in this series of 42 figurative subjects is rendered solely in black and white and devoted to a famous character, like Glaukos, who, originally a fisherman, became a sea god in the form of a merman with the gift of prophecy after consuming a magical herb (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Glaukos, from the series ‘Greek Mythology’

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1965

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 45.7 × 60.3 cm

Gift of Sue Y. S. Kimm and Seymour Grufferman (2019.78.78)

Fig. 6 Circus No. 6

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1968

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper with mica, 49.5 × 77.5 cm

Gift of Sue Y. S. Kimm and Seymour Grufferman (2019.78.79)

Following his return from a brief teaching assignment at the University of Oregon in 1967, Hagiwara elaborated on the use of wild, swirling lines in the series ‘Fairyland’ (‘Otogi no kuni’) and integrated humanoid forms into his compositions, like in the ‘Circus’ (‘Saakasu’) and ‘Clown’ (‘Dōkeshi’) series of 1968–69 (Figs 6 and 7). While continuing to create purely abstract prints, he returned to incorporating figures in the mid-1970s series ‘Lady’ and ‘Aesop’s Fables’ (‘Isoppu ebanashi’). From 1977 to 1984, he was a lecturer at Tokyo Gakugei University, and from 1979 until 1990, served as chief director of the Japan Print Association. Throughout his career, Hagiwara created many single prints as well as more than seventy series based on a wide range of themes. These include astronomy and geometry, like the eighteen prints of the 1979–80 series ‘Starlit Night’ (‘Hoshizukiyo’), ‘Star on the Sand’ (‘Sajō no hoshi’) with twenty prints from 1982 to 1984, and ‘Locus’ (‘Kiseki’) with seven prints from 1984 to 1985. While he composed prints in series, they were limited and short-lived as he disliked repetition. In his words: ‘If I always made the same thing in the same style with the same technique in the same place, I would quit being an artist’ (Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, Hagiwara Hideo: Bi no sekai (video), 1987; author’s translation).

Between 1986 and 2013, Japan’s national broadcasting organization NHK produced three different documentaries about Hagiwara that were aired in their popular series Nichiyō bijutsukan (Sunday Museum). In 1987, Machida City Museum of Graphics Arts also produced a film about him, in which Hagiwara demonstrated how he generally printed his works by creating A Nebula No. 3 (Seiun) (see Yamanashi Prefectural Museum of Art, Hagiwara Hideo hanga sakuhin mokuroku, Yamanashi, 2013, no. 737) and elaborated on his understanding and vision as an artist. In fact Hagiwara never identified as a print artist (hangaka) but rather as a painter (ekaki), creating prints with the same feeling as if painting in oil. He strove to bring out the depth of space in prints and to make prints that would be comparable and not inferior to paintings. Learning from the past was important to him, and he collected art so that he could study traditional artworks and techniques in order to develop new methods and techniques himself.

Fig. 7 Clown No. 8

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1969

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper with mica, 76.2 × 49.5 cm

Gift of Sue Y. S. Kimm and Seymour Grufferman (2019.78.80)

Fig. 8 The Sky is Aflame, from the series ‘Thirty-six Fuji’

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1981–86

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper with mica, 40.2 × 53.3 cm

Gift of Gordon Brodfuehrer (2018.105.11)

After decades of designing abstract prints, in 1981 Hagiwara Hideo turned to landscapes, with a focus on Mount Fuji, Japan’s holy mountain (Figs 8 and 9). Inspired by Katsushika Hokusai’s (1760–1849) iconic series of prints from the early 1830s, Hagiwara wanted to create a modern view of the mountain. The series, which he called simply ‘Thirty-six Fuji’ (‘Sanjūroku Fuji’), was a challenge since access to the mountain had become much easier in modern times, and he endeavoured to provide new viewpoints. In his own words: ‘Mt Fuji defies all challenges. That is why people approach it with cameras and drawing pens. Whether it looks noble or vulgar depends on your mind’s eye. Today’s appearance is not the same as tomorrow’s. Even if you think you have captured its essence, it always escapes from between your fingers. Now, I will glean the images of Mt. Fuji which have escaped me’ (College Women’s Association of Japan, 56th CWAJ Print Show: Japanese Contemporary Prints, Tokyo, 2011, p. 113). Hagiwara completed the series in 1986 and his novel views and lively use of colour proved a great success.

Again in the vein of Hokusai, who had expanded his initial Fuji series of 36 pictures to 46, Hagiwara designed a sequel of twelve prints titled ‘Gleanings of Mt Fuji’ (‘Kobore Fuji’), from 1990 to 1991 (Fig. 10). In parallel, he devised an extravagant series of gigantic views called ‘Great Fuji’ (‘Ōfuji’), which are almost double his original series in size and thus command an impressive presence. He issued seven of these new and enlarged views of Mount Fuji, up until 1998.

Fig. 9 Fantasy after Rain, from the series ‘Thirty-six Fuji’

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1981–86

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 40 × 53.2 cm

Gift of Gordon Brodfuehrer (2017.142.2)

Fig. 10 An Evening Moon, from the series ‘Gleanings of Mt Fuji’

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1990–91

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 57.2 × 41.3 cm

Gift of Gordon Brodfuehrer (2018.105.16)

Over the course of his career, Hagiwara won awards in Japan, Switzerland, Slovenia and Slovakia, and was honoured by the Japanese government. In 1988, on the 20th anniversary of the bestowal of the Nobel Prize for Literature upon Kawabata Yasunari (1899–1972), Hagiwara produced five commemorative works on themes from Kawabata’s novels. Not all series on a specific theme were completed in the short time frame of a few months; some, he revisited after more than a decade. One such example is Face No. 5 (Kao) from 1991, which is part of a multi-year series begun in 1978 and completed in 1993 (Fig. 11).

At the age of 94 Hagiwara Hideo passed away, in 2007. His legacy, however, lives on.

Fig. 11 Face No. 5

By Hagiwara Hideo (1913–2007), 1991

Woodblock print, ink and colour on paper, 67.8 × 56.5 cm

Gift of Gordon Brodfuehrer (2019.138.27)

Andreas Marks is Mary Griggs Burke Curator and head of the Japanese and Korean Art Department at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The exhibition ‘Abstract Prints by Hagiwara Hideo’ is taking place at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in two rotations: the first is on view until 25 October 2020 and the second, from 31 October 2020 to 18 April 2021.

All the prints illustrated in this article are in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

This article first featured in our September/ October 2020 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.