An Interview with Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang

In what is the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s largest capital gift ever, Oscar L. Tang and his wife Agnes Hsu-Tang have pledged $125 million for the renovation of the museum’s Modern Wing, which encompasses 80,000 square feet (7,400 square metres) of galleries and public space. The redesigned wing—to be named in honour of the couple—is not only an update of the physical space but is a ‘re-envisioning’ of the Met’s display of modern and contemporary art to incorporate a more interdisciplinary, encyclopaedic, and global approach. Mr Tang is a trustee emeritus and generous decades-long benefactor of the Met, as well as chair of the museum’s Asian Art Visiting Committee. Agnes Hsu-Tang is a respected academic and international cultural heritage policy adviser and a member of the Met’s Modern and Contemporary Art Visiting Committee.

‘With this historic gift, the Tangs are emphatically expanding their portfolio at the museum to include modern and contemporary art, and I know that their encouragement will further push the museum to expand its treatment of the 20th and 21st centuries beyond the Euro-American canon.’ Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang Associate Curator of Chinese Painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In addition to her academic pursuits and work with the Met, Hsu-Tang is also chair of the board of trustees at the New-York Historical Society and, since 2015, chair of its Exhibitions Committee. Under her leadership, exhibitions ranging from ‘Exclusion/Inclusion: Chinese American’ (2014–15), a history of Chinese in the United States, to ‘Harry Potter: The History of Magic’, for which she translated and elucidated the legendary 7th century Dunhuang star chart, were made possible and meaningful to a wide range of visitors.

‘At the New-York Historical Society, she has been an advocate for establishing dialogue between contemporary art and our historical collections as a means of activating both and of prompting reflection upon the past and what it means for the present.’ Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto, senior curator of American art at the New-York Historical Society

Orientations: After years of supporting acquisitions, exhibitions, and other endowments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, what were the reasons behind donating to the Modern Wing in particular?

Oscar Tang: While in the past I have primarily supported the acquisitions, conservation, research, curation, and exhibitions of historical Asian art, some years ago I realized that given the vibrancy of Asia and the ongoing and diverse artistic expressions flourishing in the region, the Met’s Asian art department needed to move forward into the modern and present period. Agnes and I had acquired a few works of contemporary Chinese art here and there, but about five years ago Agnes became very active and serious about putting together a meaningful collection of Indigenous modern and contemporary art.

Agnes Hsu-Tang: In addition to historical Chinese art and the art of the Greater Gandhara, a recent focus of our collection has been modern and contemporary Indigenous art in the United States. Because I am a scholar of archaeology and ancient art history, people are often surprised that we do not collect historical or ethnographic Indigenous materials. That is an intentional decision on our part. As Chinese Americans who have contested—Oscar in his leadership roles at the Met Museum, New York Philharmonic, and Andover, and I in my scholarship and roles at the New-York Historical Society and the Met Opera—the entrenched Orientalist curatorial approach to our own culture, we hope to help stop the perpetuation of the fetishizing of Indigenous peoples and cultures in the colonialist mode of the ‘noble savage’.

I grew up in an international, diplomatic community on the East Coast and was exposed to a diversity of languages and cultures, but American schools taught me very little about the peoples who first inhabited and flourished in America before Columbus’s arrival in 1492. I was introduced to Native American cultures in college through the writings of activist-writer-poet N. Scott Momaday, the first Native American to be recognized with a Pulitzer award. Curious about my adopted country, I drove across America for the first time and visited reservations during the summer after college. What I saw and learned shook me to the core. I learned that descendants of the first Americans have been systemically enslaved, murdered, and banished from their ancestral land since the 1840s under the guise of ‘Manifest Destiny’, and many on reservations live in poverty-stricken conditions without water and or electricity. I knew what I witnessed on the reservations was systemic cultural genocide.

I went on to advanced studies in foreign policy and archaeology, and became engaged in work on cultural heritage protection and academia. For the last twenty years I have travelled and worked in remote parts of the world, and when someone expressed that they wished they were living in America, sometimes I would tell them about the plight of the first Americans. It is for this reason that I collect modern and contemporary Indigenous art—to expose the enduring devastation of colonialism and to show that Native Americans are not invisible—that they live amongst us. I hope to see Indigenous talents recognized in the contemporary vernacular and to see cultural institutions represent Indigenous voices in the narrative of the shaping of America.

Advocating for the inclusion of Indigenous and other historically marginalized heritages—our own included—in the modern and contemporary milieu, is a critical part of our donor intention. We hope to see the Met’s Department of Modern and Contemporary and the Modern Wing be a platform for the advancement of the scholarship, discourse, interpretation, and presentation of peoples and cultures beyond the Western canon. We must remember that it was not so long ago that Asian art was still considered ‘primitive’ in Western museums.

Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang

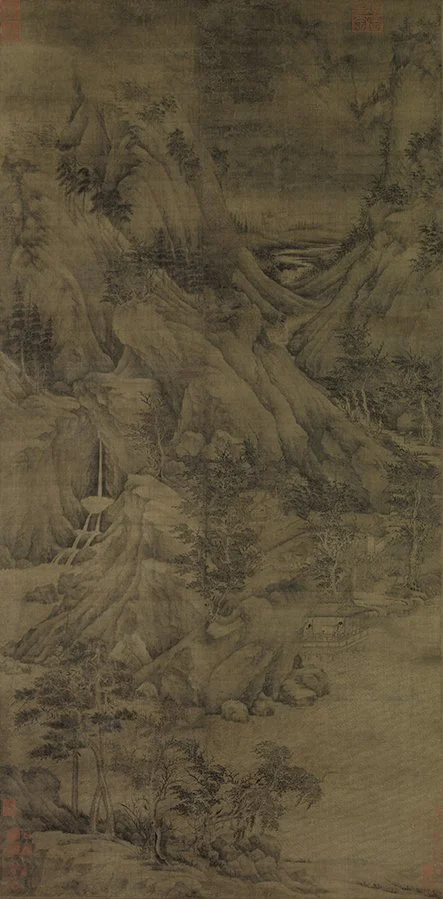

Riverbank

Attributed to Dong Yuan (act. 930s–60s); Southern Tang dynasty (937–75)

Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk; 220.3 × 109.2 cm

Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of Oscar L. Tang Family, in memory of Douglas Dillon, 2016

Metropolitan Museum of Art (2016.750)

OT: It was Douglas Dillon (1909–2003), former US Treasury secretary and the Met’s visionary president and later board chair, who built the Asian art department into what it is today. Dillon convinced the board of the critical need of integrating historical Asian art into an encyclopaedic museum; he recruited my late brother-in-law, Wen Fong (1903–2018), a Princeton University professor who pioneered the field of East Asian art history in North America, to lead the charge. With early vital support from Brooke Astor and other luminaries, Dillon and Fong together were the lodestar that guided the Met to become the global leader in Asian art that it is today. It is for this reason that we dedicated the landscape painting Riverbank in memory of Douglas Dillon, and that the Asian Art Study Room is named after Wen Fong. Our gift of the Modern Wing is a continuation of what they started at the Met—breaking boundaries.

Having travelled widely in Asia in the last decade and seeing Agnes engaged in what she calls ‘activist collecting’ of modern and contemporary Indigenous art has ultimately led to my realization that the full implementation for the Met is to incorporate all the artistic traditions of the world; in other words, for all humanity to be expressed in the global interpretation of modern and contemporary art.

O: The current renovation has been in the planning for over a decade. How involved will you be in advising the new presentation of modern and contemporary art and cultures within the new galleries?

OT: As a long-time trustee, I have watched the Met’s efforts to rebuild the Modern Wing for more than a decade and have seen this evolution towards using the modern and contemporary to extend and juxtapose all the different cultures of the world, whose art is historically dispersed and represented in different departments throughout the museum. I hope to be a voice in the planning of the new presentation of modern and contemporary art with this global orientation in mind.

O: In your thirty years of service as a trustee of the Met, have you observed any notable transformations in the museum’s curatorial approach to reflect the world’s increasingly globalized cultural exchange?

OT: During my time as a trustee, I have seen the Met gradually evolve from a somewhat silo-ed departmental structure to the point where the metaphorical and physical walls that divide the different departments have begun to fall, taking on a curatorial approach that is increasingly reflective of the intersection of the world’s diverse cultural and artistic traditions. I believe that the new director, Max Hollein, is particularly focused on presenting both a more globalized and interdisciplinary vision.

O: You have served as a long-time chair of the Met’s Asian Art Visiting Committee. How do you wish to see Asian arts and culture integrated with the rest of the Met’s collection in the future?

OT: I wish to see the Asian art department extend its collections and presentations into the modern and present times, while also integrating its historical works and perspectives into the Met’s modern and contemporary department to represent Asia’s contributions to the current dialogue.

O: In the past you have donated many important gifts of historical Chinese art to the Met—will there be more opportunities for interaction between traditional and contemporary art in the new renovated galleries?

OT: I would hope that the Asian art department, which is so strong in its collections and presentation of traditional Asian art, will work closely with the modern and contemporary department and Modern Wing to tell the histories and evolutions of Asian cultures into the present and in the context of the world and mankind as a whole.

O: The past few years have been turbulent times globally; how do you see the promotion of art being able to transcend borders and reconcile cultural polarization?

OT: In the way that art is an expression of the human experience, I see the promotion of art as a medium of human exchange that can help reconcile cultural polarization.

O: The Covid-19 pandemic has greatly transformed how art is being experienced globally, with many exhibitions moving online. How do you think the younger generation, increasingly accustomed to virtual reality, may benefit from visiting the Met’s Modern Wing and museums in general?

OT: I think that the widespread availability of virtual experiences with art can be educational in terms of understanding the art and explaining the art, but, that it will ultimately lead to a greater desire to see and experience the actual work of art because it is through that direct experience where the full impact of the artistic expression can be appreciated.

O: Dr Hsu-Tang, you have dedicated many efforts to public arts education in both your work as a scholar and trustee and now chair of the New-York Historical Society. What new opportunities do you envision the Met’s renovation of the Modern Wing to provide for students and the general public?

AHT: I am humbled and deeply honoured to become the first Asian American to be elected board chair to an American history museum. The New-York Historical Society is New York’s first museum and the third oldest cultural institution in American history, founded in 1804.

Palace Banque

By unidentified artist Chinese (act. late 10th–11th century); Five Dynasties (907–60) or Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) period

Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk; 161.6 × 110.8 cm

Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of Oscar L. Tang Family, 2010

Metropolitan Museum of Art (2010.473)

White Tara and Green Tara

Western Tibet (Guge); 1450–1500

Distemper on cloth; 51.4 x 50.8 cm

Zimmerman Family Collection, Purchase, Oscar L. Tang Gift, in honour of Agnes Hsu, 2012

Metropolitan Museum of Art (2012.460)

Having chaired the New-York Historical Society’s Exhibitions Committee for seven years, I have witnessed how our robust offerings of public arts education—programming, curricula, internships, and curatorial and research fellowships—have contributed to progressive changes in the arts and culture sector that reflect the diversity of present-day America. In 2019, I worked with our senior administrators and curators to create the New-York Historical Society–City University of New York Master of Arts in Museum Studies programme. This formidable partnership of two of New York City’s leading public institutions provides a high-quality and affordable graduate curriculum with a focus on public history and collective heritage that aims to diversify the museum workforce and address the needs of an increasingly diverse and engaged museum-going public.

Based on my experience in developing and supporting this programme, I know there is a tremendous demand for public arts education, from K–12 curricula to postdoctoral training. I hope to see the Met becoming a leader in diversity hiring in every aspect of its operations, especially among the curatorial ranks and in senior administration. With the building of the Modern Wing, I believe firmly that the Met is the only global museum that has the potential to present visual histories of all peoples of the world, from the ancient past to the present.

‘The Master in Museum Studies programme at the New-York Historical Society provides a meaningful career path for diverse students, and it has become a main point of entry into the museum profession for several hundred diverse and economically challenged students.’ Louise Mirrer, president and CEO of the New-York Historical Society

O: You recently supported the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition ‘Dreaming Together’, a collaboration with the Asia Society following the launch of its first triennial, titled ‘We Do Not Dream Alone’, a retrospective of important American artists of Asian descent. How do you think such collaborative efforts might encourage cross-cultural dialogue?

AHT: I had the privilege of working with Dr Ikemoto on the Asia Society Triennial’s collateral exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. The original concept of this exhibition predated the collaboration, as Wendy and I had talked about a transnational, trans-Pacific retrospective of important American artists of Asian descent, whose works remain unexplored by Euro- and American-centric art institutions. Anchored on Wendy’s curatorial vision, and with advisory input on contemporary Asian art from Boon Hui Tan, the triennial’s founding director, this unprecedented institutional partnership produced an important intellectual dialogue that compelled viewers to reconsider how historical entrenchments have shaped present-day America. While Boon Hui’s triennial presented an unflinching confrontation of vestiges of Orientalism by forty contemporary artists (one deceased) from 21 countries, ‘Dreaming Together’ contested the historical perceptions of ‘American-ness’. These two exhibitions further served as a rare platform for diasporic artists of Asian heritage around the world, who have been historically marginalized by both their ancestral and adopted societies. Equally important was the timing of this collaborative effort—we persevered against all odds during Covid-19, and this pair of original, multi-artist exhibitions were among the first to open, safely and responsibly, to the public and for the public, since the pandemic first struck New York City. We made deft curatorial changes in response to, in sequence: Covid-19, an extended lockdown of New York City, amplified racism and violence against people of Chinese and East Asian descent, a global economic recession, the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd that galvanized nationwide Black Lives Matter protests, and the 2020 American presidential election. The purpose of a contemporary art platform is to exhibit a visual history of the present; in this light, ‘Dreaming Together’ impelled us to confront historical traumas unfolding in real time. Further, the inclusion of three works created by artists during and for Black Lives Matter protests—two of which are by Asian artists—gave us a rare, emic view of these artists as activists, in action.

A particular pairing in this exhibition stood out in the context of the mission of the New-York Historical Society. Inside the venerable institution’s grand Dexter Hall, two monumental cityscapes of New York framed the hall’s ends: on the southern wall, a pair of 100-foot-long hanging scrolls of abstract photography by the transnational Vietnamese and American artist Dinh Q. Lê capturing the explosive collapse of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001; across the length of the hall, American artist Richard Haas’s iconic, nearly 60-foot-wide panorama of southern Manhattan. This pairing depicts a tale of two cities—Haas’s Manhattan is a megalopolis at the pinnacle of its awesome might as the global centre of finance, arts, and culture; in stark contrast, Lê presents New York in an apocalyptic state as the very symbol of its economic might, the Twin Towers, explodes and disintegrates into ashes. These contemporary images echo the theme of the cycle of civilization in the Hudson River School masterpiece series, ‘The Course of Empire’, exhibited on the western wall of Dexter Hall. Created almost two centuries ago, Thomas Cole’s iconic work has become a prescient, pessimistic allegory of current US history, as Covid and divisiveness continue to shatter the illusion of Pax Americana.

The New-York Historical Society has boldly undertaken a series of trailblazing, courageous, and for some ‘uncomfortable’ exhibitions in the last seventeen years that re-examine US history from the perspectives of the disenfranchised. ‘Dreaming Together’ was a powerful addition to the series, which began in 2005 with the landmark exhibition ‘Slavery in New York’ and includes the critically acclaimed and groundbreaking exhibition ‘Exclusion/Inclusion: Chinese in America’, in 2014–15

‘Dreaming Together’, originated and organized by the 218-year-old New-York Historical Society, as part of the first-ever art festival on contemporary Asia in the United States, signifies the power of inclusion and partnership. By working together in unity, and in reciprocity, this exhibition demonstrated the beautiful possibility of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr’s vision of a common dream for all in America, where ‘we are free at last’.

‘Museums have a responsibility to engage with big questions; contemporary art, particularly as it concerns the diasporic experience and cultural conflict and connection, offers one way to do that. By interweaving the Asia Society collections with our own, we were able to create pointed juxtapositions that challenged more iconic, traditional understandings of America and American art. This type of cross-cultural and cross-institutional work is what will advance the field.’ Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto

This article first featured in our March/ April 2022 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.