Creating Spaces for Asian Art: C. T. Loo and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, is renowned for its important collection and evocative displays of Asian art. The art dealer C. T. Loo, or Ching-Tsai Loo (Lu Qinzhai in pinyin; 1880–1957), played a pivotal role in both of these strengths, through the works of art that he offered for sale and his lesser-known contributions to the design and decoration of the museum’s galleries. This article explores connections between Loo and two of the original Asian art galleries at the Nelson-Atkins: the Chinese Temple Room and the Indian Temple Room. Through their presentation of the history and contents of these rooms, the authors demonstrate how Loo’s contributions created Asian-inspired spaces in Kansas City, and in the case of the Indian Temple Room, how it drew directly from the imagined Indian interiors of Loo’s red Pagoda in Paris.

While many visitors to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art today may not know much about C. T. Loo, they do know the galleries he initiated. One of the museum’s most famous and popular spaces is the Chinese Temple Room. Developed from 1930 to 1933 (Fig. 1), this gallery assembles many celebrated treasures of Chinese Buddhist art. Equally important is the room itself, which is an outstanding example in the history of the display of Asian art in America.

The Chinese Temple Room is comprised of three interior components: The first of these is a huge mural nearly 15 metres in length, The Assembly of Tejaprabha Buddha, originally painted for a Yuan dynasty (1272–1368) building in the complex of Guangsheng Temple, Hongdong, Shanxi province. The second component is a splendid ceiling that includes a coffered vault and ceiling panels formerly installed in the upper floor of the Hall of Tathagata in the complex of the Zhihua Temple, built in 1444 of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) in Beijing. The third component is a set of twelve latticed door panels from an unidentified temple built in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). These door panels screen off the room from the larger Chinese art gallery in front of it.

Fig. 1 Entrance to the Chinese Temple Room at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation/Bob Greenspan

Loo was a creative thinker and an effective businessman. After moving part of his business to New York from Paris, Loo contacted the newly-established Nelson Gallery of Art (now the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). In a letter on Christmas Day 1930 to Jesse Clyde Nichols (1880–1950), chairman of the trustees who oversaw acquisitions for the museum, Loo wrote:

I am in the opinion that because there is no Museum in any country [that] has any Chinese gallery, I think that if you build a real Chinese gallery, especially with the Frescoes build [sic] on the walls as they were originally in China, with an antique wooden ceiling, the Gallery would be entirely Chinese and would be very becoming to exhibit the Chinese collection in future.

The fresco Loo mentioned was The Assembly of Tejaprabha Buddha, which fortunately retained a relatively full composition after being removed from the temple. To American museums in the early 20th century, murals and architectural components were sought-after essentials. They could be used to build period rooms, which were fashionable in museum design from the late 19th into the early 20th century, as inspired by European historical architecture and displays from world expositions and fairs (Harris, 2012). In the 1930’s, the founders of the Nelson-Atkins Museum were actively developing a series of period rooms to represent art from a variety of cultures.

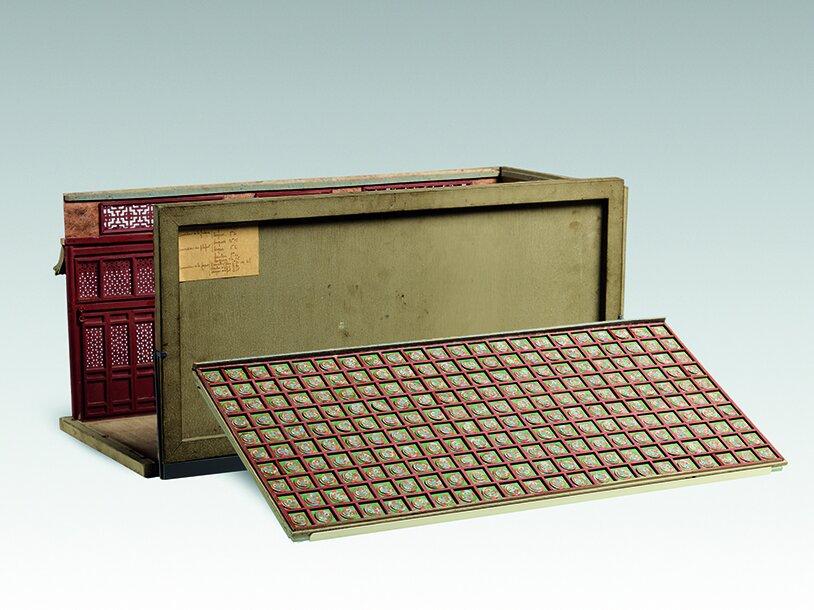

Fig. 2a Model of the Chinese Temple gallery (partial, three-quarter view)

By C. T. Loo & Company, Paris; May 1931

Wood, plywood, paper, marbled paper, paint, metal fastenings; 80 x 40.64 x 38.1 cm

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (T2017.45)

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation

Fig. 2b Ceiling view of the model of the Chinese Temple gallery

To assert his authority as an arbiter of authentic Chinese styles, in letters, Loo repeatedly used phrasing such as ‘a real Chinese gallery’, ‘entirely Chinese’, and a ‘gallery purely Chinese’ (Loo to Nichols, 1930–31). He may have tried to distinguish his concept of showing historical artworks from the 17th to the 18th century chinoiserie displays in Europe that featured elements such as pagodas, wallpapered rooms, and porcelain rooms, or from Asian export art collected in America during the 18th and 19th centuries. Loo was already displaying some of the best works of Asian art available at his flagship gallery in Paris, the Pagoda, against the backdrop of Asian-inspired interiors.

Loo worked for two years to convince the Nelson trustees to purchase the Chinese Temple Room, who were, apparently, at first reluctant to pay his costly price. In Paris, he worked with his assistants to build a 3D scale gallery model, which he presented in person to the trustees in Kansas City (Loo to Nichols, 3 March 1931; Wight to Nichols, 7 May 1931). The well-crafted model, now stored at the museum, demonstrated how to display the three components. It features a hand-painted copy of the mural on the rear wall, a set of twelve door panels at the front, and a flat ceiling painted with squares of geometric patterns (Figs 2a–b).

The potential of the Chinese Temple Room was not realized until the autumn of 1931, when Harvard professor and curator Langdon Warner (1881–1955) and his former student Laurence Sickman (1906–88), then the museum’s agents for acquiring Asian art, purchased the coffered vault and adjacent 112 ceiling panels from the Zhihua Temple in Beijing. Joyful about the acquisition of the ceiling, Nichols reconsidered the idea of a Chinese period room. With Warner’s help, Loo successfully persuaded Nichols to acquire the mural The Assembly of Tejaprabha Buddha with a promise to donate the set of twelve door panels. The objects were then shipped from Paris, and via the New Orleans Transit Railroad, to Kansas City (letters: Warner to Nichols, 17 December 1931; Loo to Nichols, 31 December 1931 and 6 January, 19 February, and 12 April 1932).

Fig. 3 Detail of blueprint for the Chinese Temple Room

By Wight & Wight Architects, 13 June 1931

Nelson Trust Records, Museum Archives, Kansas City, Missouri

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation

The assembly of the gallery followed Loo’s model, with the exception that the proposed flat coffered ceiling was replaced by the vaulted ceiling from the Zhihua Temple. The model presented a cubical room that could be tailored to fit the space of the building’s interior. Nichols and the museum’s architect, Thomas Wight (1874–1949), agreed that the layout as shown in the model could indeed work in the building (Wight to Nichols, 7 May 1931); Wight & Wight Architects drew blueprints of elevation and floor plan similar in concept to Loo’s model (Fig. 3).

The complicated installation of the gallery began in the summer of 1932. Rutherford J. Gettens (1900–74), a conservation scientist from the Fogg Museum of Harvard University, oversaw the repair and installation of the mural that had been cut into numerous blocks. The installation took several months, as Gettens recommended ‘the painting must be installed with the expectation of keeping it in place for hundreds of years’ (Gettens, 1932, p. 2). Wight then erected the ceiling about five feet away from the mural with modern beams and columns to support the weight and height (Fig. 4). Finally, the door panels were attached to the columns as a screen to the room.

The final installation shows an axial alignment from the entrance to the largest dragon at the apex of the coffered vault and ending with the Tejaprabha Buddha on the wall. Vermillion beams and columns in the style of traditional Chinese architecture added to the definition of this grandiose space, evoking a feeling of awe in the visitor, not unlike that felt inside a sanctuary. Upon Nichols’s request, Loo loaned many objects for the opening on 11 December 1933, including a wood sculpture, now known as Guanyin of the Southern Sea, which was acquired by the museum the following year (see Fig. 4). Guanyin magnificently reigned in the room as if radiating an aura. Henceforth, the Buddhist art displayed in the ‘Chinese Temple Room’ became well known to the world.

Fig. 4 Interior of the Chinese Temple Room, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation/Bob Greenspan

Fig. 5 Overview of the Indian Temple Room gallery, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Indian components, 18th century

Carved teak and mahwa wood; 763 x 488 cm

Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust (33-297)

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation

The anticipated success of the Chinese Temple Room inspired the acquisition of a second Asian gallery from Loo. In January 1933, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art purchased the ‘Indian Temple Room’ from Loo in preparation for the museum’s opening later that year. Except for wall niches added in the 1980s to display Indian bronzes, this gallery appears much the same as it did when first installed in 1933 (Fig. 5). Carved teak and mahwa wood cover this intimate space from floor to ceiling. A coffered ceiling comprised of 126 panels displaying abstract lotuses fills the full length and width of the room. Directly below the ceiling, four narrow bands of lotuses and abstracted designs nestle a frieze of 128 relief panels that wrap the full perimeter of the room and depict various deities from the Hindu pantheon. Moving down from the frieze, thirteen engaged pilasters rhythmically punctuate the walls of the gallery. These pillars, topped with pineapple-shaped finials, also feature brackets decorated with alternating rearing horses and their riders and vyalas, composite creatures meant to dispel evil (Fig. 6a). Two doorways carefully constructed from intricate carvings complete the gallery’s interior (Fig. 6b). These components come from multiple sources; the door lintels appear to come from a wood Indian building, the frieze sculptures and columns with brackets were sourced from South Indian temple carts, and the wood panelling is European and was sourced to match the Indian wood.

As an assemblage of hundreds of carved, wood components, the Indian Temple Room undoubtedly proved to be a challenging project in both conception and construction. Curiously, while many documents in the archives of the Nelson-Atkins chronicle the Chinese Temple Room’s design and installation, the history of the Indian Temple Room remained a mystery at the Nelson-Atkins due to a lack of formal documentation. After months of archival research, however, minutes from a January 1933 meeting following a buying trip to New York revealed a surprising explanation. The Indian Temple Room was originally intended for the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Archival documents shared by the Detroit Institute of Arts include fascinating correspondence between Loo and Detroit’s curator of Asiatic art, Benjamin March (1899–1934), that documents the genesis and design of the Indian Temple Room. Following a meeting in early February 1929, March wrote Loo to thank him for his recent visit to the museum and to share the following news: ‘The question of the Indian room I took up with Dr. [Wilhelm] Valentiner [Detroit museum director] and he is much interested in it … [W]e shall propose the matter to the Arts Commission and ask their approval of the experiment’ (letter dated 9 February 1929). Loo promptly replied to March, writing ‘I also feel indebted to you about the Hindu Gallery and I hope that you will soon be able to decide to undertake the experiment and that you will send me a sketch of your space so that I can arrange the gallery accordingly’ (letter dated 12 February 1929). The repeated use of the word ‘experiment’ suggests that both March and Loo viewed the Hindu gallery for Detroit as a unique opportunity to create an immersive gallery designed to steward a greater appreciation of Asian art for the general public.

Fig. 6a Detail from Figure 5 showing a carved bracket with horse and rider

Fig. 6b Indian Temple Room doorway with carved lintels, brackets with vyalas, sculptural frieze, and coffered ceiling

Photo © The Nelson Gallery Foundation

During the next two years, Loo and March regularly corresponded about the Hindu gallery. March provided a detailed gallery plan with meticulous measurements, and he even helped translate the information into French for Loo’s design and construction team in Paris. In September 1930, Loo shared a promising update from Paris, reporting, ‘I am working hard on your Hindu Gallery. We are completing the ceiling now … We are trying to make the [frieze] (modern) to put on the top [of] the pillars and I will bring you the model before putting it in execution’ (letter dated 10 September 1930). In late December 1930—just as Loo proposed the Chinese Temple Room to the Nelson-Akins—models of the Hindu gallery arrived in Detroit. Using the models and Loo’s design drawings, March prepared a formal proposal for Dr Valentiner and the Arts Commission. In it, March interestingly referenced Loo’s Pagoda, explaining that the overall design of the Hindu gallery follows ‘somewhat the same plan that he has employed in his gallery in Paris’ (memorandum dated 26 January 1931). Then in detail, March described that the proposed Hindu gallery included ‘the construction of an open facade’, with the back of the room covered with ‘plain panels made of old wood, divided by pilasters carrying the flying figures—horsemen, animals, etc’. Above the panelling, a frieze of carved panels was to be topped by a ceiling of carved wood. Except for the facade, this description exactly matches the Indian Temple Room installed at the Nelson-Atkins. Unfortunately, the financial impact of the Great Depression prompted the Detroit Institute of Arts to postpone a decision on the acquisition of the room indefinitely. The new Hindu gallery stored in Loo’s warehouse in Paris now needed a new buyer.

The perceived success of the newly installed Chinese room influenced the Nelson-Atkins to acquire an Indian room. Typically a businessman not known for exaggeration, museum trustee Nichols remarkably declared in a November 1932 letter, ‘The Chinese room is a knockout. The temple ceiling, fresco, doors, etc. are all installed and are very beautiful’ (Nichols to A. Hyde, 11 November 1932). Soon after, discussions of an Indian room appeared in the November 1932 board meeting minutes: Nichols reported that ‘there is a possibility that Langdon Warner will go to Japan next year and can return by India and through his connections there perhaps secure an Indian temple interior which would add greatly to the interest of our Gallery’ (‘Meeting of November 25, 1932’). This plan suggests that Nichols was likely unaware of Loo’s available room in Paris. While it is not known how the negotiation for the Indian gallery began, the Nelson trustees finalized the purchase during a visit to New York in late January 1933 (‘Meeting of February 5, 1933’). After its arrival at the Nelson-Atkins, the Indian gallery, which the museum originally called the ‘Hindoo Temple Room’, was installed adjoining the ‘Persian Room’, across the hall from the Chinese Temple Room, creating a suite of Asian galleries ready to receive visitors during the museum’s opening in December 1933.

The Indian Temple Room gallery is an invention born in Paris; it does not represent the treatment of actual wood temple interiors in South India. Its ornate columns are reminiscent of stone colonnade temple halls in Tamil Nadu, and similar rows of Hindu deities are more likely to be found in the registers and niches of South Indian temple exteriors, not interiors. Loo stated to March (cited above) that they were ‘completing’ the lotus ceiling of the room, and further study may reveal that it is in fact more French than Indian.

Fig. 7 Pagoda Paris, 8th arrondissement, Paris, 2014

Photo © Photononstop/Alamy Stock Photo

Fig. 8 View of gallery with skylights at the Pagoda Paris, c. 1928

Image courtesy of Baroness Jacqueline von Hammerstein-Loxten

The Indian gallery that was planned for Detroit and realized in Kansas City was based upon the Salle Indienne, the gallery created for exhibiting South Asian art at Loo’s Pagoda in Paris. In 1925, Loo purchased a multi-storey, free-standing home in the 8th arrondissement and transformed it into a gallery for Asian art. Known as the Pagoda Paris, the exterior was renovated to appear like a multi-storey red brick, tile-roofed Chinese house (Fig. 7), while the interior spaces were decorated in regionally-inspired styles, including Chinese lacquer rooms, an Indian gallery, and a Southeast Asian wing. With the renovations completed by the late 1920s, the Pagoda Paris opened its doors to the public with the purpose of showing Asian art in Asian spaces. Visitors could walk through a Qing-inspired lacquer room in the heart of Haussmannian Paris and imagine what living with a work of Asian art in a domestic space would be like. Loo’s house of art was carefully conceived and completely modern. Its ceiling was pierced by a grid of contemporary skylights rendered in the Chinese ‘thunder pattern’ (Fig. 8), and its historicizing rooms opened onto an Art Deco–styled spiral stairwell that encapsulated a state-of-the-art elevator. Located in the centre of Europe and the European art trade, the Pagoda stood as a celebratory symbol of ‘Asia’ and its treasures. This vision of Asia was predominately Chinese in terms of its design and square footage, and pointedly at this historical moment, it did not reference Japan. Purpose-built and completely self-conscious, Loo’s Pagoda presented a new kind of Orientalism for a modern age.

Inside the Indian gallery of the Pagoda Paris today, visitors find themselves in a narrow wood chamber surrounded by exuberant carvings (Fig. 9). Turbaned riders on elephants and rearing horses prance above their heads (Fig. 10). These are the same columns and carved brackets as found in the Nelson-Atkins Indian gallery. Clearly, Loo and his craftsmen used the same source materials—local wood and a pool of components from disassembled temple carts—to create both rooms. The Salle Indienne in Paris is further decorated with carved components from Jain ghar derasar (home shrines) (Fig. 11) and carved domestic doorframes. There are two Jain shrines and sections of at least four doorways embedded in the panelled walls. The Jain shrines appear stylistically similar to examples from Gujarat and Rajasthan. Installed without Jinas (enlightened beings) inside them and currently without doors in front, the Jain shrines at the Pagoda serve as mementos of temple architecture rather than as potentially functional shrines in this space. Instead, they helped to create an aura of sacred space in order to contextualize the Indian sculptures that were displayed in the room.

The success of his Asian galleries in Paris inspired C. T. Loo to offer his invented Asian rooms for sale to museums, as well as individual works of art. In designing these galleries, Loo demonstrated that he was an innovator in the presentation of Asian art, an early practitioner of what today we might call ‘museum experiential design’. Loo believed that the proper environment was critical for the appreciation of Asian art and that what worked in a saleroom would also work in a museum. The two galleries he proposed for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art incorporate actual works of art. Yet, each room is also an assemblage of different materials and components, of different dates, and sourced from different sites and regions. To Loo, a well-designed space for art, even if not wholly accurate, could still create an authentic and powerful response in the visitor. If the popularity of the Chinese and Indian Temple Rooms at the Nelson-Atkins can serve as evidence, C. T. Loo was correct.

Fig. 10 Detail of Figure 9 showing carved brackets with horses and riders; note the similarity with carvings at the Nelson-Atkins Indian Temple Room as seen in Figure 6a

Photo © Kimberly Masteller

Fig. 11 One of the Jain shrines installed in the Indian gallery, Pagoda Paris

Photo © Kimberly Masteller

Ling-en Lu is Curator of Chinese Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; Kimberly Masteller is the Jeanne McCray Beals Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; and Michele Valentine is the former Department Assistant of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.

The authors wish to thank the following individuals for their generous assistance with research and for providing access to sites, archival materials, and photographs for this article: Baroness Jacqueline von Hammerstein-Loxten, Director, La Maison Loo, Paris; James Hanks, Archivist, the Detroit Institute of Arts; Joshua Ferdinand, Manager, Media Services, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; MacKenzie Mallon, Provenance Specialist, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; and Tara Laver, Senior Archivist, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Selected bibliography

Correspondence in text (various), unless otherwise noted below, found by date and author (RG80/10), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Archives, Kansas City, https://nelson-atkins.libraryhost.com.

Rutherford J. Gettens, ‘Record of Examination and Recommendation for the Installation’, 6-7 July 1932 (RG 80/05), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Archives, Kansas City.

Neil Harris, ‘Period Rooms and the American Art Museum’, Winterthur Portfolio 46, no. 2/3 (2012): 117–37.

C. T. Loo, letter to Benjamin March: 12 February 1929 and 10 September 1930 (Records of the Curator of Asiatic Art, Benjamin March, 1927–1931, RG ASI, Series 1, Box 3, Folder 11), Detroit Institute of Arts Research Library & Archives, Detroit.

Benjamin March, letter to C. T. Loo, 9 February 1929 (Records of the Curator of Asiatic Art, Benjamin March, 1927–1931, RG ASI, Series 1, Box 3, Folder 11), Detroit Institute of Arts Research Library & Archives, Detroit.

—, ‘Memorandum to Dr. Valentiner’, 26 January 1931 (Records of the Curator of Asiatic Art, Benjamin March, 1927–1931, RG ASI, Series 1, Box 5, Folder 7), Detroit Institute of Arts Research Library & Archives, Detroit.

‘Meeting of February 5, 1932’ and ‘Meeting of November 25, 1932’, Board of Trustee Minutes (William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records, 1926–1933, RG 80/05, Series 1, Box 4, Folder 3), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Archives, Kansas City.

This article first featured in our March/ April 2023 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.