John Thomson’s Photography of Hong Kong: Picturesque Landscape and ‘Types’

A finalist paper in the inaugural Susan Chen Foundation & Orientations Young Art Writers Award 2024.

Born in Edinburgh, John Thomson (1837–1921) was a Scottish geographer, traveller, and photographer. He was the first known photographer to document China and, unlike most Western photographers of the time who stayed in the coastal treaty ports, he travelled to the interior of China. In 1868 he moved his photography studio from Singapore to Hong Kong, using the latter as his base for further travel into mainland China until 1872. Thomson’s photographs fall into two broad themes: scenic views and ‘types’ of people, an early anthropological categorization of colonized population groups based on physiognomy; and indeed, both landscapes and portraits of ordinary people comprise his photography of Hong Kong (Hockley, 2010). This essay analyses John Thomson’s Hong Kong photography and examines how his picturesque images and portraits of types reinforce the Victorian British notion of Hong Kong as ‘the birthplace of a new era in eastern civilization’ (Thomson, 1873, p. i), and how early photography practices embodied cross-cultural interactions in the territory.

Leaving Edinburgh in 1862, young Thomson’s early travels took him across East and Southeast Asia. He returned to Britain briefly, but a year later, in 1867, he resumed his Asian travels, opening a photo studio in Penang, staying a short stint in Saigon, establishing his photography business in Singapore, and finally moving to Hong Kong. There, he set up his studio in the Commercial Bank building on Queen’s Road, Central, and served as the official photographer of the Duke of Edinburgh’s 1869 visit to Hong Kong. From Hong Kong, he travelled extensively in China. Later in 1872, he returned to London where he occasionally served the British royal family. After writing articles and providing photo illustrations for magazines, including China Magazine and Illustrated London News, Thomson acquired some fame as a writer, photographer, and traveller. He catalogued his photographs from his travels and published them in books, including Illustrations of China and Its People, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China, and China, and The Land and People of China. He also published articles on photographic techniques and how to manoeuvre a camera in tropical climes.

Not only did photographing in tropical climates brought technical difficulties, such as the environmental factors of heat and humidity, but the new technology also faced varying degrees of resistance. Thomson described a fear of foreigners among the Chinese, as the scholar-officials had fostered alarm over the fan qui, or foreign devil, who would take over their souls (Thomson, 1873, p. i). Photographs—technology brought by Westerners—were perceived as haunted objects that could take away sitters’ souls (British Council, 1992, p. 2). Nevertheless, Thomson managed to build important connections in China, meeting vital commercial and political figures, and even making portraits for Prince Kung (Yixin), the regent of the Qing empire from 1861 to 1865. Thomson’s photographs of aristocrats and various groups of ordinary people belie local fears, and the varying degrees of acceptance of the photographic technique marked different attitudes, presumably based on class distinctions, towards Westernization in China and the camera as an important object of cross-cultural encounters (Gu, 2014, p. 159).

1

City of Victoria

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. II)

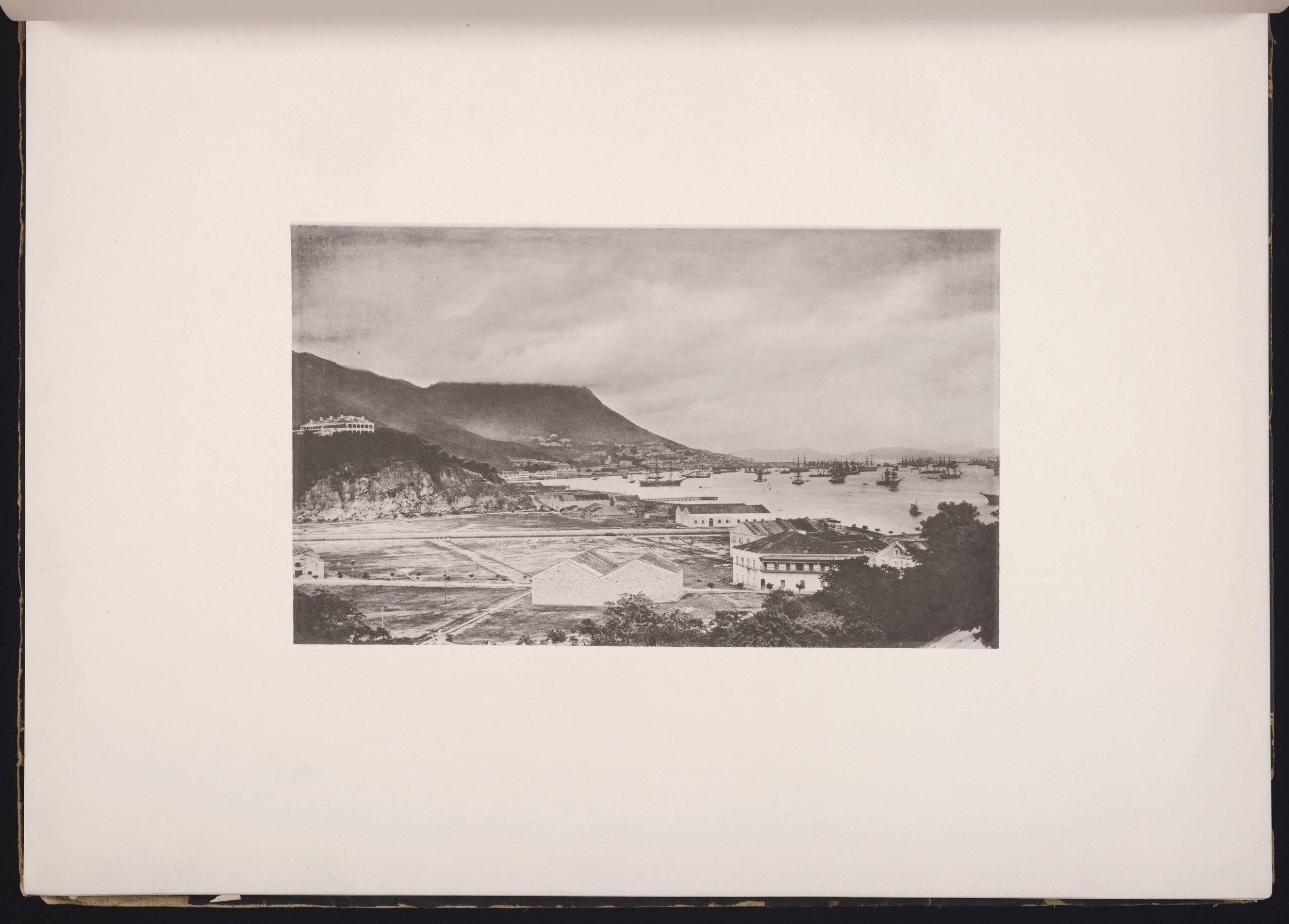

Thomson repeatedly described his photography of the Hong Kong landscape as ‘picturesque’, an 18th century aesthetic concept developed by the English painter-essayist William Gilpin (1724–1804). A picturesque image encompasses a dark, detailed foreground, an imposing middle ground, usually with open water, and a hazy background of mountain and sky, with trees appearing at the edges to frame the image. Thomson clearly deployed a similar visual language in his photographs of Hong Kong. In the photograph City of Victoria (fig. 1), trees frame the lower half of the image, and the open landscape of Happy Valley’s racetracks lies in the foreground, with European architecture on the right. These images are reminiscent of 19th century paintings of the British countryside, but the motifs of plants, architecture, and the geographical landscape have been replaced with those of the new colony.

John Thomson’s aesthetic values are deeply rooted in Victorian British tastes and seem unaffected by the artistic practices of East Asia (Thomson called ‘the Far East’). While scholar Stephen White argues that Thomson’s composition philosophy coincides with the ideas of Daoist landscape painters such as the 11th century Chinese artist Guo Xi (c. 1020–c. 1090), there is no direct evidence of his acquaintance with this Chinese aesthetic idiom apart from his collection of Chinese paintings (1989, p. 40). Instead, Thomson wrote about the beauty of Happy Valley, his favourite place in Hong Kong (see fig. 1), referencing ‘what Mr Ruskin says of composition’ to secure the aesthetic achievement of the unity of nature (ibid). Indeed, the complex lights and shades, the irregularity and asymmetry of the composition presented by the contrast of mountain and sea, and the ‘parasitical manner to the building’ cohere with what John Ruskin defines as the picturesque (Landow, 1971, p. 225).

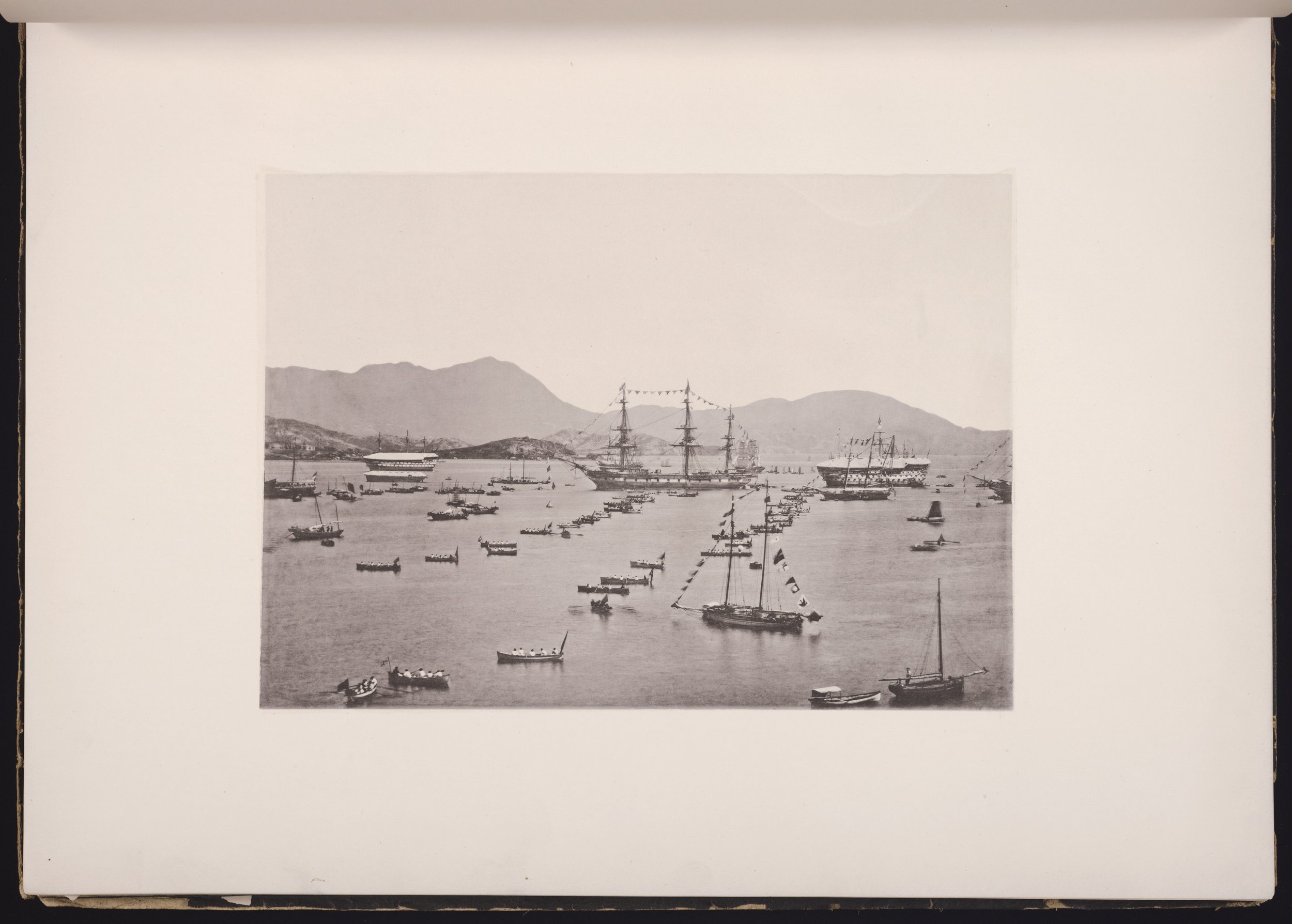

As Jeffery Auerbach argues, the picturesque served to ‘unite and homogenize the many regions of the British empire’ (2004, p. 47). British painters and photographers used this compositional structure of the English landscape to depict images of their colonies, such as the images of India by the English painter William Hodges (1744–97). These images, which conveyed a familiar yet exotic sense of the colony, circulated widely in Britain. Thomson’s photographs, likewise, were published and disseminated in newspapers and books. Furthermore, in his photographs of Hong Kong with mountains and the sea, he has a clear predilection for panoramic views from high vantage points. This view was favoured by other photographers of the time as well; for example, Italian-British photographer Felice Beato (1832–1909), who travelled to Hong Kong in 1860s, has a similar composition of the City of Victoria taken from Happy Valley. The contrast between the dark mountains and the white facades of the buildings emphasizes the grandeur of the new European architecture that was gradually taking over the Hong Kong landscape (fig. 2). As art historian Allen Hockley argues, this composition is a visual analogy that the Western influence is civilising the land of China (Hockley, 2010, p. 1). The panoramic views of Hong Kong not only capture the beauty of the land, but also the consolidation of British settlement in the colony.

2

The Harbour

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. III)

3

The Clock Tower, Hong-kong

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. IV)

Though one may refute Hockley’s argument as an art historical overreading, Thomson’s Victorian colonial mindset and prejudices are apparent in his writings when he makes judgments about the places he visited. In his introduction to Illustrations of China and Its People, he states:

I shall start from the British colony of Hong-Kong, once said to be the grave of Europeans, but which now, with its city of Victoria, its splendid public buildings, parks and gardens, its docks, factories, telegraphs and fleets of steamers, may be fairly considered the birthplace of a new era in eastern civilization.

(Thomson, 1873, p. ii)

Similar comments are also made about the foreign settlements in Shanghai: ‘… as to lead a visitor to fancy that he has been suddenly transported to one of our great English ports’ (ibid). In Thomson’s judgement,

The crowd of shipping, the wharves of warehouses, and landing-stages, the stone embankment, the elegance and costliness of the buildings, the noise of traffic in the streets, the busy roads, smooth as a billiard-table, and the well-kept garden that skirts the river, affording evidence of foreign taste and refinement, all tending to aid the illusion.

(ibid)

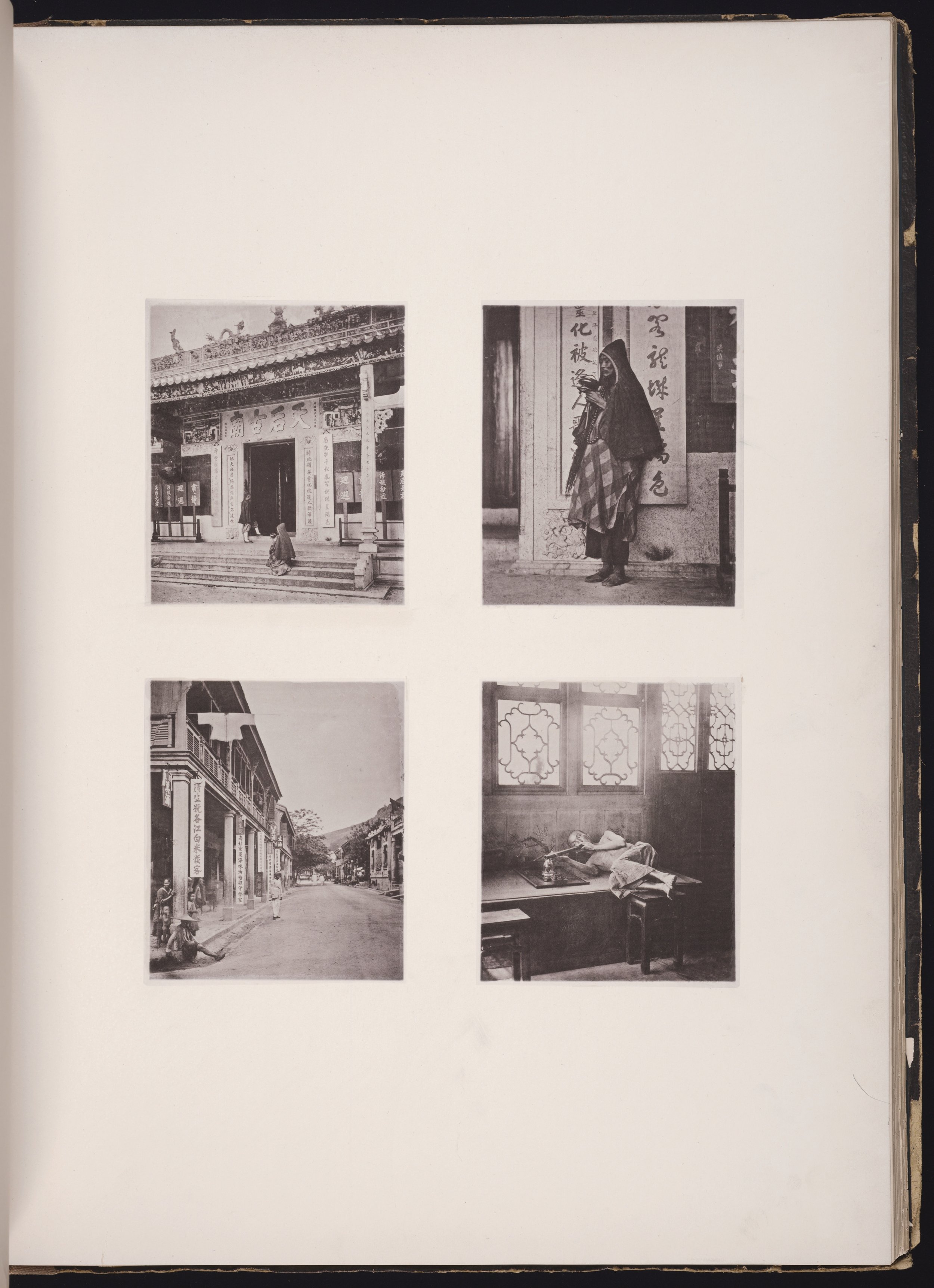

For Thomson, the compatibility of the new infrastructure with European (and perhaps American) cities marked the advancement and progress of Eastern civilizations, and these modern constructions gave him a positive impression of the city. His photographs of European architecture are horizontal, emphasizing the breadth and width of rows of arches and columns and wide boulevards (see fig. 3). Meanwhile, his compositions of Chinese residential areas in the streets of Hong Kong are vertical and more close-up to highlight the compact shops on the streets, which emphasizes the individuality of the city (fig. 4). He seemed genuinely interested in local cultural practices, such as temple worship and tea picking, and documented them in his travelogues as encounters with folk practices. Interestingly, while Thomson provided many details on local Guanyin worship, his photograph of the Kwan-Yin Temple is in fact a Tin Hau Temple, likely the one in Causeway Bay, dedicated to Mazu (also known as Tin Hau in Cantonese), a Chinese sea goddess, rather than Guanyin (see fig. 4). In contrast to his lengthy description of the modern glamour of colonies, he did not consider Hong Kong to have a history—the city was ‘barren and uninteresting … where one can find nothing more than a few fishing hamlets’ (ibid., p. i). The two different modes of representation for European and Chinese settlement in Hong Kong imply Thomson’s linear perspective on civilization, which saw Western infrastructure as progressive, while the local was interesting, but not quite modern.

4

Various closeup photos of the streets and people of Hong Kong, including an opium smoker (lower right)

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. IX)

Thomson was known in Victorian Britain for his rich and authentic account of travels in East Asia; his photographs of Hong Kong were mainly of the seaside in the City of Victoria (Praya and Queen’s Road to Happy Valley). A review of his work in the Pall Mall Gazette, a London evening newspaper, commented, ‘No picture of Chinese manners at once so full and so vivid has yet been attempted ... There is scarcely any side of Chinese life ... of which he has not secured some record’ (November 11, 1874). He gained such recognition chiefly because of his use of the camera not as an artistic medium for capturing landscapes or individual portraits, but as tool for the documentation of people of different classes and folk practices in Chinese societies.

Thomson photographed ordinary Chinese residents in Hong Kong, including priests, musicians, an artist (more on that later), schoolboys and girls, and so forth. Compared with his formal portraits, such as the photograph of Prince Kung, these are ‘types’ rather than individuals, as he used their occupations, not their names, in his photo titles and short articles accompanying the illustrations, even when their names were known. Documenting types is an attempt to categorize and order people from lower social classes by generalizing them into professions rather than naming individuals (Ovenden, 1997, p. 71). It sprang from the studies of physiognomy and anthropology in modern Europe, and Victorian artists began utilizing these tropes to paint images to tackle social problems, like what Thomson later did with his photographs of the London urban poor published in Street Life in London (ibid).

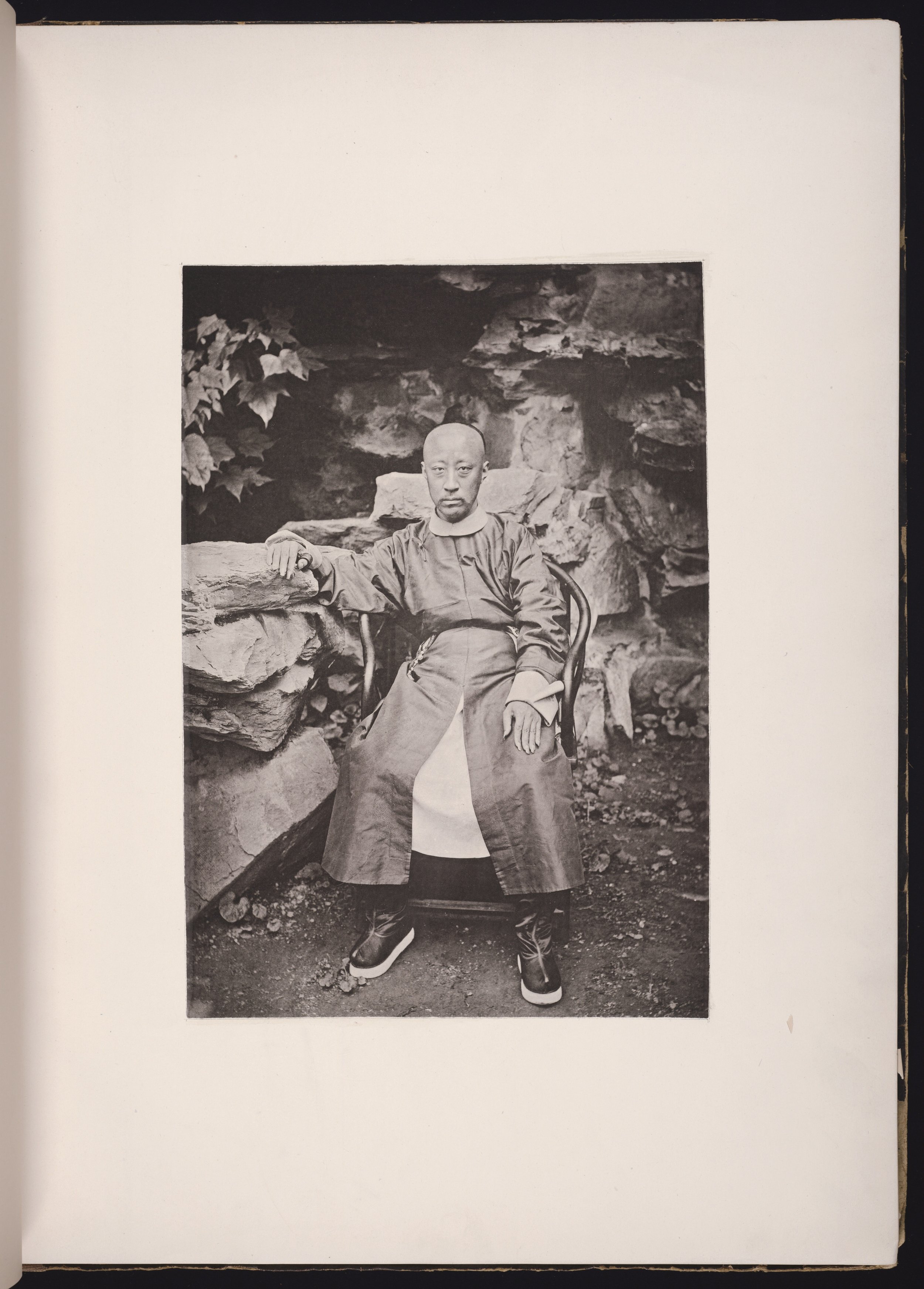

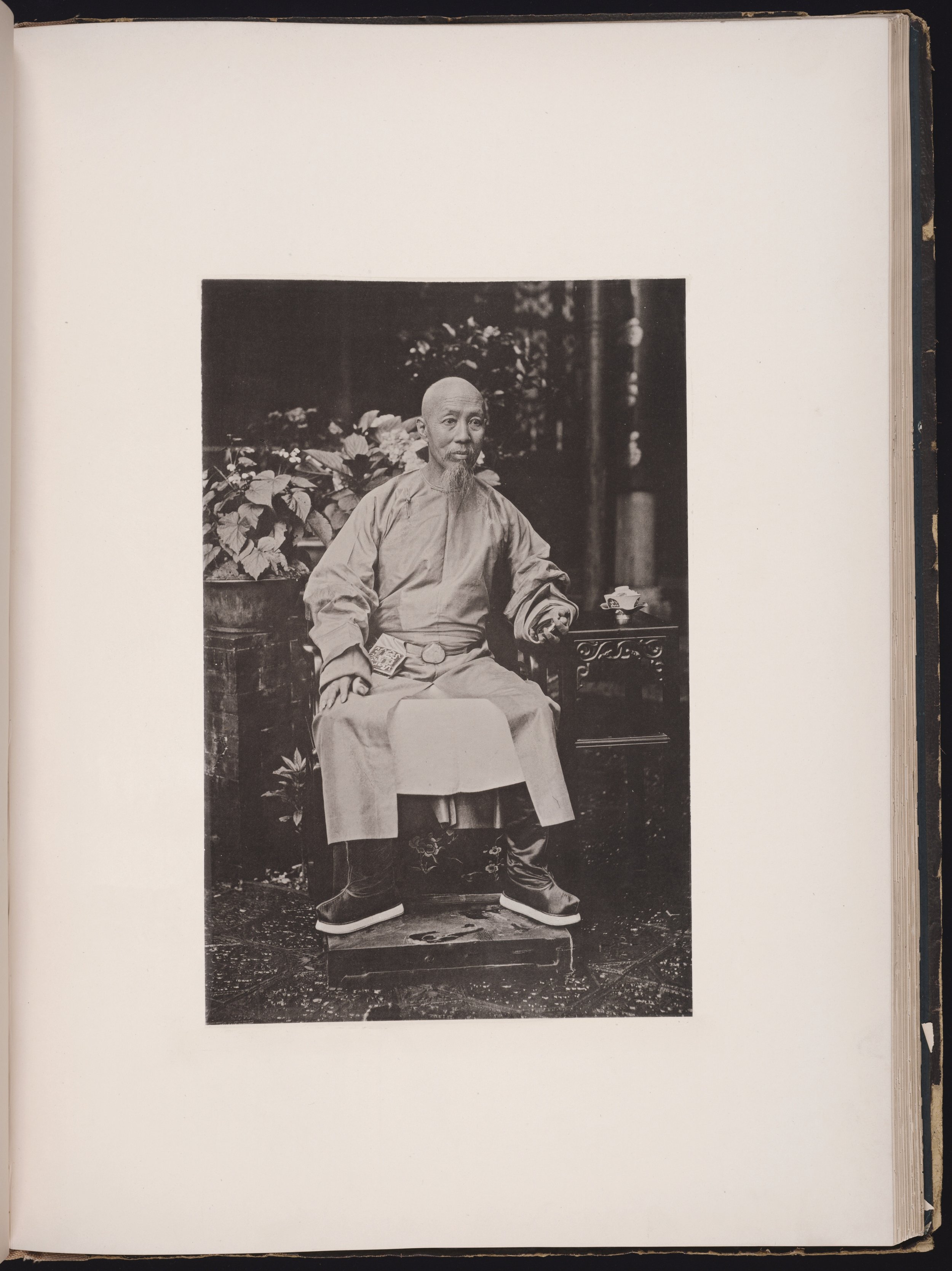

In Thomson’s photography, one important visual cue that marks the difference between a type and an individual is if the sitter is in a formal frontal posture. Western photographers in China, including Thomson, noted the visual code of Chinese formal portraiture, in which Chinese sitters are to be seated in full-frontal orientation, in a strictly symmetrical pose, and with furniture in a similarly rigid position. In Thomson’s photographs, notable figures such as Prince Kung (fig. 5) and Jui Lin (Ruilin, the governor-general of the two Guang provinces) (fig. 6) have their individual portraits taken in the standardized pose, seated in a chair with a domestic scene in the background. The sitters of types are photographed in groups, engaged in activities or holding objects such as musical instruments to show their occupations, or in individual profile photos displaying their clothing, hairstyles, or other physical features. The photographs of types do not aim to depict a single person, but instead use the person as an example to document the physiognomic and other visual features of a particular race, ethnic group, occupation, or social class that could be easily distinguished by appearance.

5

Prince Kung

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. I)

The standard posture in early photographs not only differentiates the sitter as an individual from a type but also marks the cross-cultural encounter between Western photographers and Chinese sitters. Thomson wrote about such practices and even drew a parody of Chinese portraits and published it in the British Journal of Photography (fig. 7) to illustrate what he saw as artificial regularity, as seen in his portrait of Prince Kung and other upper-class Chinese patrons. His fellow photographers agreed, criticizing the rigidity of the Chinese pose. Though it accords with pre-existing codes of Chinese imperial portraiture, art historian Wu Hung argues that these conventions were only recorded by Western observers, and that the postures of sitters in Chinese or Western studios were not significantly different (2016, p. 29). Meanwhile, Chinese writers or photographers did not see the Western portrait poses as homogeneous in Western studios. This shows that Western photographers working in China consciously constructed a Chinese-style visual language of portrait photography in their studios using a mode of representation to adapt to local custom and consequently reshape people’s ideas about the camera, though it is likely based on misunderstanding of Chinese portraits.

Among Thomson’s documented types, one unique case is his portrait of a professional artist, Lam Qua (1801–60; also known as Lumqua and as Kwan Chiu Cheong), who worked in Canton (Guangzhou) and had a workshop near the Thirteen Factories, a neighborhood along the Pearl River that was the principal and sole legal site of Western trade with China in the late 18th and early 19th century (fig. 8). According to Thomson, Lam Qua was the pupil of George Chinnery (1774–1852), the first English painter to settle in China, who was well known for his Western-style oil portrait painting. Modern scholars, however, have found that Chinnery denied the pupillage relationship (Chang, 1993, p. 468). As the first Chinese oil painter exhibited in the West, Lam Qua is a notable figure in late imperial Chinese export art. Despite his success, in Thomson’s book he is simply labelled as ‘A Hong-kong Artist’. The photograph shows Lam Qua only from the side, without details of his face, while emphasizing his action of creating an easel painting and his studio environment, with completed works hanging on the wall. It provides details about the figure, but ultimately reduces him to an example of a Hong Kong artist.

Thomson called Lam Qua ‘A Hong-kong Artist’ despite the fact that his studio was actually in Guangzhou. On the one hand, Thomson’s familiarity with Lam Qua’s biography and both cities, as well as Lam Qua’s fame as one of the best Chinese oil portraitists of the time, shows the tight connections in trade and artistic exchange between the Thirteen Factories in Guangzhou and Hong Kong; on the other hand, the blurred geographical and conceptual boundary of Canton vis-à-vis the actual city of Guangdong shows that Canton was a term and concept that only existed among Westerners in China in relation to export art (Koon, 2019).

6

Jui-Lin, Governor-General of the Two Kwang Provinces

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. XIII)

7

Drawing by John Thomson (1837–1921)

(After ‘Parody of Chinese Photographic Portraits’, British Journal of Photography, XIX/658, 1872)

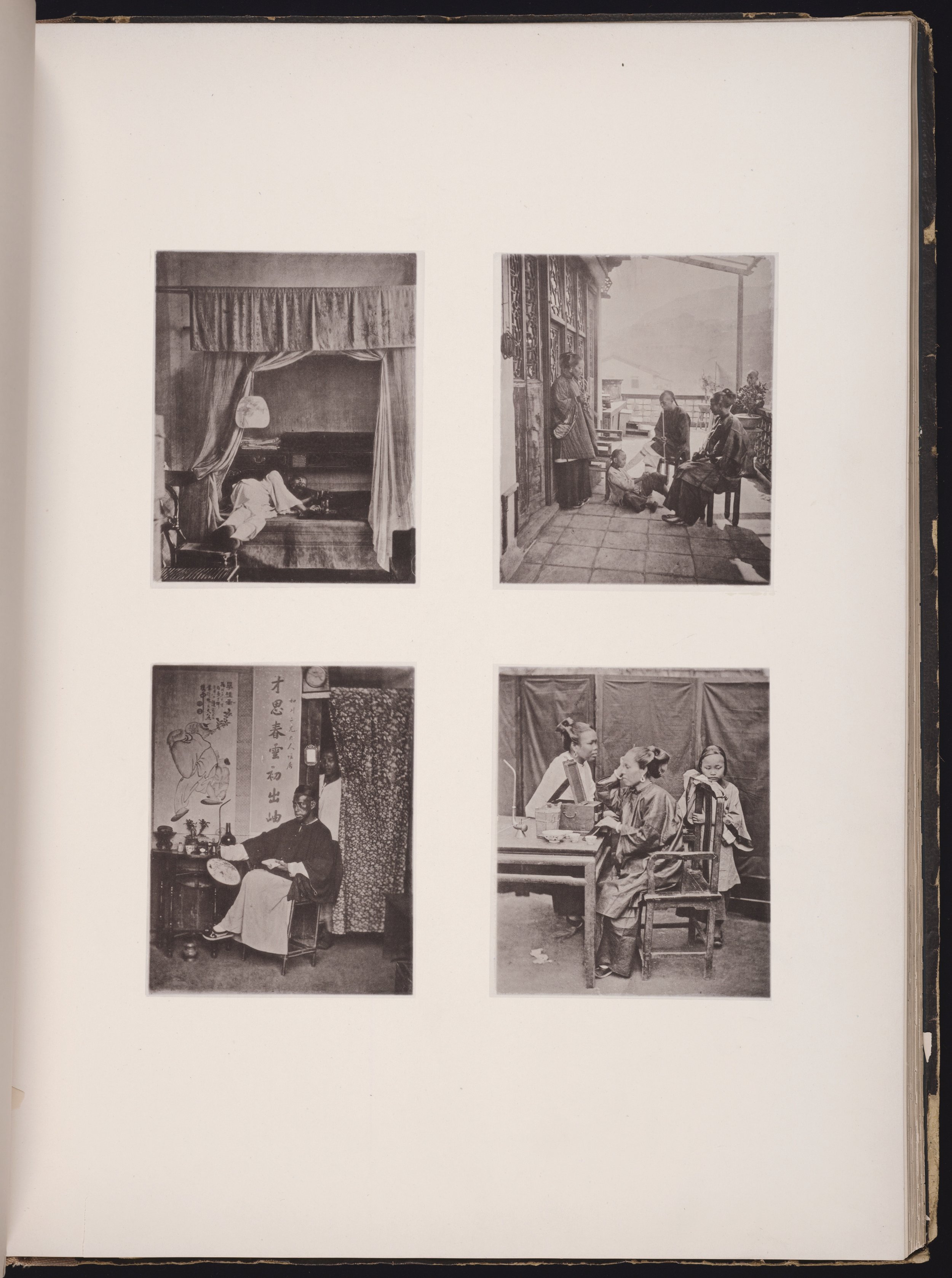

Photographs of types have been criticized as an instrument of colonial and imperial domination in colonies and the subjugation of anthropology and photography to such ideologies, but Thomson’s documentation adds slight nuances to such an argument. In his writings, he shows sympathy for hard-working sedan-chair coolies and the devastating effects of opium on Hong Kong households (Thomson, 1873). His photographs of men with opium, in particular, do not follow the formula of types at all (fig. 9). These photographs are positioned closely within domestic spaces and show each man lying in bed with his body almost perpendicular to the picture plane, providing an intimate glimpse into Chinese households affected by opium. At the same time, the photographs also cater to and reinforce the British preconception and impression of Chinese men who indulge in opium as ‘sick men of Asia’. Similarly, although he states the necessity of the achievements of Chinese educated in government English schools, he insists they can be no more than copycats or accountants due to their insufficient acquaintance with English (ibid). In commenting on the types he photographed in Hong Kong, Thomson showed genuine interest in, and to some extent sympathy for, local people, while maintaining hierarchical preconceptions based on culture and race.

Despite the vivid excitement of the travelogue, Thomson still called Hong Kong ‘the grave of Europeans’ and wrote about the difficulties of dealing with snakes and diseases and the high cost of living for Europeans in Hong Kong (Thomson, 1875, p. 181). His accounts of the backlash against colonial rule in Hong Kong extended stereotypes from the landscape to the people. For example, he wrote of piratical outrages in Hong Kong, ‘so confirmed is their relish for buccaneering … in spite of the heavy penalties now imposed upon the crime’ (Thomson, 1873, p. i). He also cites the British horror over the Esing Bakery incident, a food contamination scandal on 15 January 1857, when hundreds of Europeans were poisoned by arsenic in bread from the Easing Bakery. Thus, the organization of the police, according to Thomson, improved the morality of the local population, as ‘the wealthy and respectable class of native residents’ joined in suppressing crimes (ibid., p. ii). The European construction of an impression of grotesque horror in the East is central to the discourse on orientalism and postcolonialism, and Thomson proved no exception, despite the relative authenticity of his accounts of both landscape and people.

John Thomson’s photographs and essays of picturesque landscapes and social types go hand in hand in constructing an attractive yet grotesque Hong Kong. His landscape photographs featuring panoramic views of European architecture set against vast tropical hills are composed according to the principles of the picturesque, aesthetically homogenizing Hong Kong as a place in the British Empire. His photographs of street scenes and local people as types representing certain occupations or social classes reflect the Victorian anthropological and physiognomic idea of classifying people, which, despite his expression of sympathy, removes their individuality. His writings on Chinese people’s fear of the camera and Westerner photographers’ perception and distaste of the standardized Chinese portrait pose offer an interesting look at the camera as an object embodying cross-cultural encounters. Thomson’s genuine curiosity and adventurous spirit, as well as his prejudices and assumptions of British supremacy belied in his writings, provide a detailed account of one individual’s mentality in cross-cultural interactions in 19th century Hong Kong, and reveal the British concept of Hong Kong modernity in terms of its compatibility with European infrastructure and social organizations.

Xinyi Ye is a MA candidate at University of Pennsylvania, Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

All images unless otherwise noted are courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Luke Gartlan of University of St Andrews and Professor Greg M. Thomas of The University of Hong Kong for the introduction to John Thomson’s work, judge panelists of the Susan Chen Foundation Prize, Yifawn Lee and Kelly Flynn of Orientations, and Matthew Kolasa for their help in polishing the article.

8

John Thompson’s portraits of ‘types’, including a photograph of the Canton artist Lam Qua (lower right)

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. IV)

9

John Thompson’s portraits of ‘types’ in interior and exterior settings

By John Thompson (1837–1921)

(After Illustrations of China and its People, London, 1873, pl. X)

Selected bibliography

Jeffrey Auerbach, ‘The Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire’, The British Art Journal 5, no. 1 (2004): 47–54.

British Council, John Thomson: China and Its People, 1868–1872, Hong Kong, 1992.

Karina H. Corrigan and Stephanie H. Tung, eds., Power and Perspective: Early Photography in China, New Haven, 2023.

Yi Gu, ‘Photography and Its Chinese Origins’, in Tanya Sheehan and Andres Zervigon, eds., Photography and Its Origins, 2014.

George P. Landow, Aesthetic and Critical Theory of John Ruskin, 1971.

Richard Ovenden, John Thomson (1837–1921): Photographer, Edinburgh, 1997.

John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China: Or, Ten Years’ Travels, Adventures and Residence Abroad, London, 1875.

—, Illustrations of China and Its People: A Series of Two Hundred Photographs, with Letterpress Descriptive of the Places and People Represented, London, 1873.

—, ‘Practical Photography in Tropical Regions’, The British Journal of Photography XIII, no. 329 (August 24, 1866).

Stephen White, John Thomson: A Window to the Orient, Albuquerque, 1989.

Hung Wu, Zooming in: Histories of Photography in China, London, 2016.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.