Remembrance of Things Past: Negotiating a Scholar-Official Identity in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child

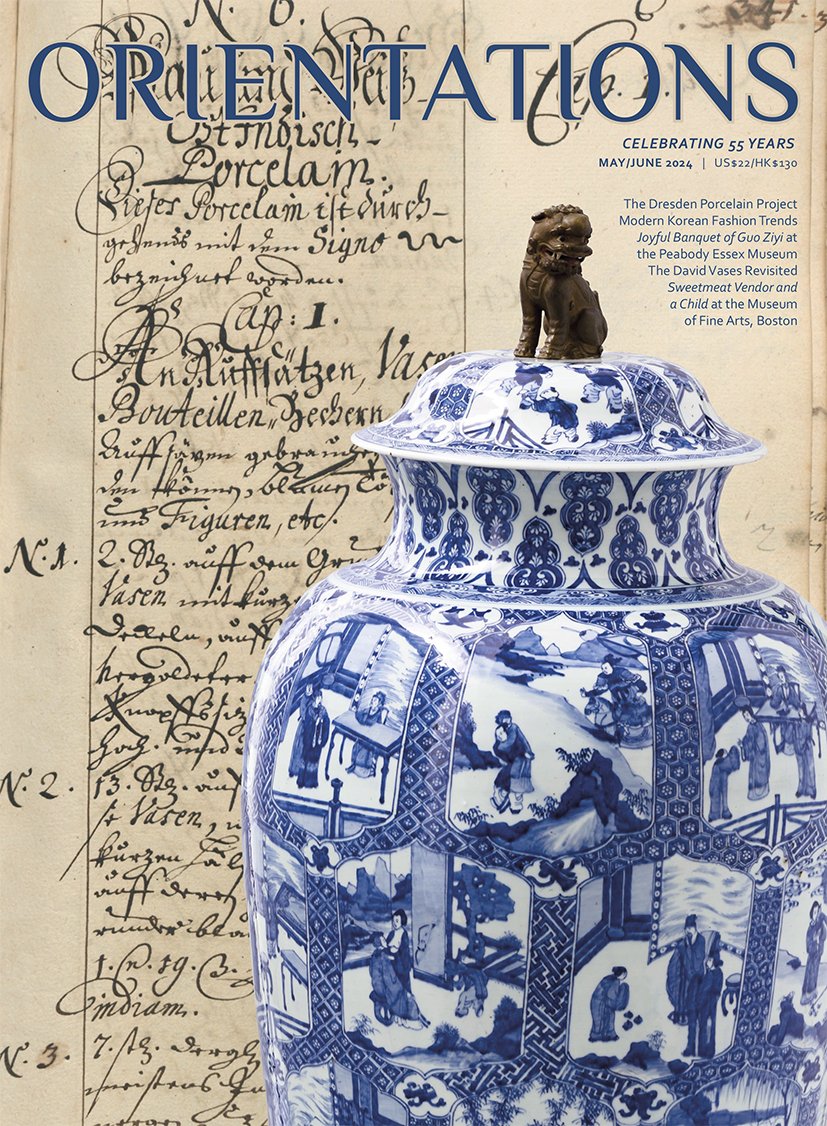

Street vendors were a popular painting subject in both the Song dynasty (960–1279) and the subsequent Yuan dynasty (1272–1368), the transition of which marked the dominion of the Mongol empire over China. In a visual study of knick-knack peddlers, art historian Huang Xiaofeng observed that representation of street vendors roughly falls into two categories: one, lavishly coloured and visually appealing, such as those attributed to the Northern Song (960–1127) court painter Su Hanchen (1094–1172); the other, rustic and monochromatic with didactic purposes, exemplified by another court painter, Li Song (1166–1264). Albeit in different styles, both acquired popularity among imperial viewers and wealthy merchants (Huang, 2007, pp. 104–5). The Yuan dynasty painting Huolang tuzhou (Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child scroll), with its rich coloration and detail, would seem to be no exception (fig. 1). However, I argue that this painting most likely held an appeal for a contemporaneous literati circle. By literati, I refer to the well-educated scholars from the Southern part of Yuan China, many of whom did not obtain officialdom in the Mongol court. While I do not intend to imply that the painting is a loyalist attempt in remembrance of the Song dynasty, it can nevertheless be viewed as a poignant retrospection of bygone grandeur. A key to this reading is a somewhat unlikely visual cue: a white radish painted on the street vendor’s fan (fig. 2).

1

Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child

Formerly attributed to Su Hanchen (1101–1161);

Yuan dynasty (1272–1368), c. 14th century

Hanging scroll, ink, colour, and gold on silk; 101.4 x 66.3 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

2

Detail of figure 1, white radish fan

Formerly attributed to Su Hanchen, Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child is now considered a Yuan dynasty artwork (Haiwai cang Zhongguo lidai minghua bianji weiyuan hui, ed., 1998, pp. 246–47). After its conquest of the Southern Song (1127–1279), the Mongol court entrusted its officialdom to the Central Asians, the Jurchen of Manchuria, and the northern Chinese, while largely ruling out those from the Southern area. To scholars excluded from public service, the expression of individual thoughts and character in paintings, a legacy of the Song dynasty, thus registered more significance (Fong, 1992, pp. 4, 379). The appreciation and practice of painting became a necessary distraction from depressed career prospects and, possibly to some, a survival strategy to shun direct political engagement. Artists at the time, most notably Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), also adopted a revivalist approach to paintings and calligraphy alike (ibid., p. 421). They studied ancient models, particularly those of the Tang dynasty (618–907), to critique and draw distance from the Song paradigm. Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child evokes such a link through the vases positioned beneath the stall’s marquee in the top right corner (fig. 3). The vases and a basket of peaches appear to float in the air. Their lack of background is reminiscent of paintings dated around the Tang dynasty, such as Nü shi zhen tu (Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies) (fig. 4). Incorporating this visual convention, Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child, as a painting of the Yuan dynasty, reveals a heightened historical awareness of the past.

3

Detail of figure 1, vases

4

Detail of Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies

Traditionally attributed to Gu Kaizhi (c. 345–c. 406); 5th–8th century

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk; 24.9 x 348.1 cm

British Museum, London

Photo courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum

Seen in this light, the subject of street vendors warrants a closer inspection in the literary context as well. After the fall of the Northern Song capital Bianjing, the loyalist Meng Yuanlao (act. 12th century) wrote a memoir titled Dongjing menghua lu (The Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendour) in remembrance of the lost cityscape, in which street-vending was commonly seen:

At times when the military troop is off duty and strolls on the street, vendors play rattles in the unoccupied space. Distributing sweetmeats and the sorts, these vendors attract children and women onlookers on the street. Such was called ‘selling plums’ or ‘street-strolling’ [bajie].

(Meng, 1983–86, vol. 589, p. 141)

As a source of delight to city dwellers, street vendors bring a festive ambience. They also maintain good standards of food hygiene. Meng notes, ‘Those who sell food and drinks use clean plates, boxes, and other containers [to display their items]. Bamboo screens droop from their carriages, which makes the scene neat and endearing’ (ibid., vol. 589, p. 145). Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child visualizes what Meng observed about the interaction between street vendors and children, as well as the arrangement of stalls. It is a vignette of street-vending practice in the Song and Yuan dynasties.

Specifically, the painting depicts a vendor who sells sweetmeats and toys to children, probably around the Qixi Festival, the 7th day of the 7th month of the lunar calendar. On that day, people follow various folk customs to pray for blessings of dexterity, offspring, and romantic encounter. A Southern Song author, Wu Zimu (act. 13th century), lists the various snacks and children’s toys a vendor may sell (1983–86, vol. 590, pp. 110–11). In Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child, these snacks, such as candies, beans, and cakes, are in clean plates and boxes at the hind end of the bamboo stall. A shelf nearby also displays a variety of toys. One of the items on display is a doll clothed in red and green (fig. 5). The doll is probably a Mahoraga figurine of Buddhist origin, always portrayed in a red vest and green dress. Variously transliterated as mohouluo or moluo, among others, it embodied wishes for bearing sons and was a popular toy in the Song dynasty (Fan and Long, 2022, p. 177). As we follow the doll’s gaze, a group of children in similar clothing playing at a distance draws our attention (fig. 6). One of the boys holds a palm of lotus leaf over his head. According to Wu, it is a tradition of the Qixi Festival: ‘[On that day] children in the city will imitate the doll Moluo, holding a freshly picked lotus leaf. This tradition is from the Eastern Capital and remains unchanged till now. I do not know any of its documented origin’ (1983–86, vol. 590, p. 33). Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child thus faithfully depicts this folk tradition from the fallen capital Bianjing. Meanwhile, the seasonal connotation of late summer in the painting is accentuated in two other details: dangling sachets and the vendor’s fan. Wu notes that sachets are a popular commodity in summer and autumn (ibid., p. 110); they exude an herbal scent that can ward off insects attracted by sweetmeats. The fan pinned on the vendor’s waist, on the other hand, ushers in a small breeze to the sultry air.

5

Detail of figure 1, doll on display shelf

6

Detail of figure 1, showing children playing at a distance

Interestingly, the vendor’s fan features a curious motif—a white radish. As a culinary item, it transforms into a literary motif in the works of the pre-eminent—and exiled—Song dynasty scholar-official Su Shi (1037–1101). As suggested by Su’s adoption of the pen name Dongpo (the Eastern Slope) after his own banishment to Huangzhou, his works are also peppered by his playful self-ridicule to the vicissitudes of life. Su writes in the preface of Cai geng fu (Rhapsody on Vegetable Broth): ‘Because of my poverty, the delicacies from the sea and land are beyond my reach, so I cook turnip, radish, and shepherd’s purse to eat.’ (1983–86, vol. 1107, p. 474) These ingredients are the main components of a dish invented by Su and named for himself, Dongpo geng (Dongpo’s broth). In an essay praising Dongpo’s broth, Su writes, ‘Some may ask the teacher [where is] this natural and unaffected flavour from: is it from the roots in the earth, or the clouds in the sky?’ (ibid., vol. 1108, p. 556) The phrase tianzhen, (‘natural and unaffected’) connects this bland, vegan congee with a natural and pure state untainted by greed, fame, or even knowledge. One of Su’s poems extends this pursuit of naturalness into a bitterly humorous contemplation of his own demotion in officialdom:

I used to live in the countryside; in my humble dwelling I have delicacies.

Often using the caldron [ding] with broken legs, I cooked turnip myself.

I lost this flavour in my mid-age, when I thought of it as if in another life.

Who knows the Southern Mountain man, I just cooked Dongpo’s broth.

Within it is the root of the radish, which still has fresh morning dew.

Do not tell the high-class dandy, who indulges in the odour of meat.

(Ibid., vol. 1107, p. 365)

Of note here is the pot used to cook this dish, a caldron with broken legs. Yi Jing (The Classic of Changes) interprets this as a bad omen, symbolizing in particular unqualified statesmen who fail to shoulder their responsibility and, consequently, lose their country (Lynn, 1994, p. 455). The cooking vessel for Dongpo’s broth completes the hidden narrative of this invented dish: frugality, naturalness, and an inability to serve the state, which is Su’s biting self-ridicule. While it may seem a far reach from a motif on the fan to unrealized aspiration, the white radish, with its frequent appearance in Su’s oeuvre, was unlikely to escape the attention of literati admirers at the time. This conceit in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child thus possibly carries a literati undertone and signifies the street vendor’s social class.

The white-robed street vendor in the painting interacts with a red-clad child, who appears to be leaving the space near the edge of the painting to the viewer’s right. This interaction is similar to the painting Huolang tujuan (Itinerant Peddler) by Li Song (fig. 7). In Itinerant Peddler, the vendor also reaches out his hands to address the children. Li Song uses ink to outline the contour of his protagonists, adopting a monochromatic style known as baimiao (‘plain rendering’) usually attributed to the Northern Song painter Li Gonglin (1049–1106). At the beginning of the scroll, a child surrounded by puppies looks out from the painting. Two children in front of the vendor also meet the viewer’s eye, as if aware of our presence. Their looking back demonstrates an awareness of being looked at. It not only engages the viewer but implies that the viewpoint of this painting is from these children’s perspective. The children’s chubby faces and pudgy legs signal an abundant life, while their mischievous smiles and carefree attitudes suggest an upbringing foreign to the hardships of life. In analysing Li Song’s depiction of knick-knack peddlers, art historian Martin Powers argues that the idealized depiction of rural children carries moralistic messages. It demonstrates that compassion and humanity can reach all classes and hence become a universal human condition under the imperial rule, which would have served the emperor well (1996, pp. 140–41). The plain rendering of the subjects in these paintings reduces their sensual appeal, which may also align with didactic, moralistic purposes. Commissioned by the court, Itinerant Peddler shows the idealized life of the rural children. It also underscores the boisterous village scene with the shaking rattle-drum, barking dogs, and shouting children.

In contrast to Li Song’s austere rendition and focus on children, Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child, with its rich coloration, leads the viewer to empathize more with the vendor. His profile is at the centre of the painting, suggesting that the viewer’s perspective is at the same height. The vendor is also the only one talking in the scene, as signified by his half-open mouth. His audio presence is much more focused, yet muted, than the scene in Li’s polyphonic painting. In another contrast, the child in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child is at the margin, as if pushed aside. Although he does not claim a central position, the child still catches our eye with his sumptuous red robe. Its glittering, gold-thread embroidery alludes to an affluent life. Other objects in the painting share the exquisiteness of this red robe. The artist took pains to depict the decorative surfaces of the boxes and dishes, even though the sweetmeats within these utensils received but modest attention. The allure of these objects is almost as ethereal as ancient treasures. As art historian Ankeney Weitz notes about the antique market in the early Yuan dynasty, street peddlers could be a source of antiques if collectors had sharp enough eyes. They might have a valuable painting at the bottom of their basket, or a Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) platter as their biscuit baker (Weitz, 1997, p. 28). Arguably, the containers in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child also manifest the mystique of valuable objects.

7

Itinerant Peddler

Li Song (1166–1264); Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), 1211

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk; 22.5 x 70.4 cm

Palace Museum, Beijing

Photo courtesy of Palace Museum, Beijing

On the other hand, these dainty objects fit nicely with art historian Jonathan Hay’s definition of ‘pleasurable things’. From the vantage point of the late Ming to mid-Qing (c. 1570–1840) dynasties, pleasurable things in residential interiors were secular and portable, their sensuous surfaces conveying ‘metaphoric and affective potential’ (Hay, 2010, p. 13). These objects realize their potential and connect us to the surrounding environment by infusing a sense of visual pleasure (ibid., pp. 8–13). Indeed, the boxes in the bamboo stall in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child are a delight to the eye for their decorative patterns. One of the four boxes, for instance, has lush spirals on its lacquered, carved surface (fig. 8). It features a pattern known as the ‘pommel scroll’ popular in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection has a similar box (fig. 9). On a surface level, these distinguishable patterns immediately call forth matters of cultural taste and social identity in our minds. At the same time, they consciously refer to their structures as containers (ibid., pp. 25, 92). Ironically enough, what they contain is something so mundane as children’s snacks—the affect is a paradoxical sense of uselessness.

How to account for such irony in Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child, then? Going back to the earlier discussion of the white radish on the fan, part of the allegory is an unfulfilled aspiration to serve one’s country. In Su Shi’s works, the white radish links the ideas of frugality and the self-ridicule of a failed career. Like the literati of the Yuan dynasty, Su Shi also received little appreciation from his emperor. His career as a government official was far less established than his literary achievements. In an essay entitled Bao hui tang ji (On Wang Shen’s Hall of Precious Paintings), Su argues that a cultivated connoisseur should only admire, instead of being obsessed with, valuable objects, particularly calligraphy and paintings. He notes his own attitude upon transforming:

On seeing things that were attractive, I would occasionally still collect them, but if someone took them away, I would have no regrets. It is like the mist and clouds that pass before one’s eyes or the [sound of] various birds that strike one’s ears. How can they not be received with pleasure? Yet, once they are gone, how can they be missed? Thus, these two things [calligraphy and painting] constantly give me joy and could never become my obsessions.

(Bush and Shih, 2012, p. 234)

To educated Southern Chinese in the Yuan dynasty, Su’s writings must have struck a chord. Faced with the Mongol court’s disposal of their civil service, scholars from the Southern area lost both the means and the purpose to serve. They had no choice but to turn to calligraphy and paintings to perfect their character. As the philosopher Mencius (372–289 BCE)—highly respected by scholar-officials and those in becoming—taught,

Men of antiquity made the people feel the effect of their bounty when they realized their ambition, and, when they failed to realize their ambition, were at least able to show the world an exemplary character. In obscurity a man makes perfect his own person, but in prominence he makes perfect the whole Empire as well.

(Lau, 2003, pp. 288–89)

8

Detail of figure 1, exquisite boxes

9

Octagonal box with pommel scroll pattern

China; Ming dynasty (1368–1644), c. late 14th–early 15th century

Carved black lacquer with red layers; height 13.3 cm, diameter 22.5 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child represents this dilemma in its visual cues. In the contrast between exquisite containers and a rustic fan, the painting would have reminded the contemporaneous literati circle of balancing their political ambition and personal perfection. It may have asked its viewers to let go of the failure to realize the aspiration of becoming a scholar-official. Yet, with its very presence, the painting poignantly hints at the inability to dismiss these thoughts, which only soak in deeper each time the viewer conjures up the folk life of Bianjing.

For literati in troubled waters in the Yuan dynasty, Sweetmeat Vendor and a Child is a painting to console their failed ambition. In conversation with Su Shi’s oeuvre, the painting can be seen as a retrospection of an unredeemable past. It visualizes not only the street-vending scene fondly recollected by memoir writers such as Meng Yuanlao, but also the literati’s dilemma between personal cultivation and public service, the latter almost impossible in the Yuan dynasty. As such, one cannot help but pause to speculate on the identity of the white-robed elder in the painting: Has he always been a street vendor? What is his past?

All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

Acknowledgements

Ocean Wang is a recent graduate in art history from the University of Hong Kong and the winner of the inaugural Susan Chen Foundation & Orientations Young Art Writers Award.

The author is greatly indebted to Roslyn Hammers for reading drafts and offering invaluable feedback to improve this article. Thanks are also due to Ruby Leung Pui Yi, who provided significant insights into the identification of the ‘pommel scroll’ pattern in the painting. The author would like to thank Yeewan Koon and Yifawn Lee for their comments and shortlisting of this article. Editor Kelly Flynn provided generous help in honing this paper.

Selected Bibliography

Susan Bush and Hsio-yen Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, Hong Kong, 2012.

Chen Fan and Yanghuan Long, ‘The Secularization of Religious Figures: A Study of Mahoraga in the Song Dynasty (960–1279)’, Religions 13, no. 2 (2022): 177.

Wen C. Fong, Beyond Representation: Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy 8th–14th Century, New Haven, 1992.

Jonathan Hay, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China, London, 2010.

Huang Xiaofeng, ‘Le shi hai tong wan zhong xin: Huolang tu jie du’, Gu gong bo wu yuan yuan kan 2 (2007): 103–17.

D. C. Lau, trans., Mencius: Revised Edition, Hong Kong, 2003.

Meng Yuanlao, Dongjing menghua lu, Taipei, 1983–86 (reprint of a Qing dynasty Qinding siku quanshu edition).

Martin Powers, ‘Humanity and “Universals” in Sung Dynasty Painting’, in Maxwell K. Hearn and Judith G. Smith, eds, Arts of the Sung and Yüan, New York, 1996, pp. 135–145.

Su Shi, Dongpo wenji, Taipei, 1983–86 (reprint of a Qing dynasty Qinding siku quanshu edition).

Wu Zimu, Meng liang lu, Taipei, 1983–86 (reprint of a Qing dynasty Qinding siku quanshu edition).