‘Saints and Kings: Arts, Culture and Legacy of the Sikhs’

With nearly 27 million adherents worldwide, Sikhism is among the world’s largest major religions, albeit one of the youngest. Sikhs are active members of their communities wherever they may be—in the UK, Canada, the US, Malaysia, Australia and of course, in India. The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco celebrates the heritage of the Sikhs with the exhibition ‘Saints and Kings: Arts, Culture and Legacy of the Sikhs’ (10 March–18 June 2017). Thirty artworks drawn from the museum’s own collection in a range of media, including paintings, photographs and textiles, explore three aspects of Sikh identity: religion, courtly culture and the community’s history in California.

The story of Sikhism cannot begin without mention of its dynamic founder, Guru Nanak (1469–1539). The artworks in the exhibition’s first section present a glimpse of Guru Nanak’s life and teachings, and aspects of Sikh religious practice. Born into a Khatri (a mercantile Punjabi Hindu caste) family in a village in the Punjab province of modern Pakistan, Nanak displayed early in life the qualities of philosophical-mindedness and compassion that would mark his later years as a spiritual leader. In a painting from the late 1700s Nanak is shown as an elderly bearded man, wearing simple robes and holding a book in his left hand (the position of his right hand suggests that he should have been holding prayer beads, but they are absent from the painting) (Fig. 1). His pose and attire identify him as a religious figure, and this is confirmed by the Persian caption above the portrait, which says that it is a picture of the Darvish Nanak Shahi. The term ‘darvish’ (‘mystic’ or ‘renunciate’) is typically associated with Muslim Sufis, but here seems to be used in a broadly generic way to designate a venerated holy man; ‘Nanak Shahi’ can be interpreted as ‘Nanak the king’, and is also one of several terms by which Sikhs were known generally by the 1700s. No images of the Guru are known from his lifetime, with most representations starting from around 150 years after his death; they are idealized images reflecting the artistic styles current in the region in which they were produced.

Fig. 1 Guru Nanak

India, probably Lucknow or Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, c. 1770–1800

Opaque watercolour on paper, 49 x 33.7 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.60)

Guru Nanak’s teachings emerged in India at a time when most of the Punjab region’s population practised Hinduism, Islam or their numerous sectarian variants. Nanak’s message of monotheism combined what he saw as the essential truths of contemporary faith-practices with his own insights into the nature of the divine. He spoke of one God—the Divine Truth—who was eternal, beyond time and representation, advocating meditation and prayer in the name of the One True God, stressing the importance of family and community life, and upholding the values of hard work, honesty and generosity. Perhaps most ‘progressive’, in contemporary terms, was his emphasis on inclusiveness and the equality of all, regardless of caste, class or gender.

Guru Nanak’s life and teachings are known from a body of literature called the Janam Sakhis (Life Stories). These accounts, which had circulated orally among early believers, were gathered over time into written (and often illustrated) collections (see Figs 2–4). The stories tell of episodes from different stages in the Guru’s life and of the people he met on his life’s journey. Not unlike types of Hindu Puranic literature, the Sakhis also describe encounters with demons and other mythical creatures. Together, they convey the Guru’s charisma and religious authority, and serve as a guide to moral action for his followers.

Nanak’s spirit of generosity and disinterest in material wealth, for instance, are exemplified in a sakhi (lit., ‘incident’). According to the narrative, the young Guru was given money by his father to purchase merchandise and start a trading career. Instead of buying saleable goods, however, Nanak used the funds to buy food for a group of ascetics. In a painting of this episode, we see the youthful Guru in red robes, beardless and with a subtle halo around his head (he is not yet the enlightened teacher), seated at the centre of a group of yogis, in discussion with their leader Sant Ren (Fig. 2). The yogis are shown with ash-covered bodies dressed only in loincloths, and many have matted hair piled on top of their heads; some, such as the yogi with his arms raised, observe forms of ascetic practice. The key Sikh values of generosity and charity were put into ritual practice by Nanak at the langar, the twice-daily communal meals offered at the gurdwara (temple) to anyone who wishes to partake.

Fig. 2 Detail of Guru Nanak and the Holy Man Sant Ren, from a manuscript of the Janam Sakhis (Life Stories)

India, probably Murshidabad, West Bengal, c. 1750–1800

Opaque watercolour on paper, 20.3 x 16.5 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.58.4)

Fig. 3 Guru Nanak’s Wedding Ceremony, from a manuscript of the Janam Sakhis (Life Stories)

Pakistan, Lahore, 1800–1900

Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 20.3 x 17.8 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.58.9)

Nanak’s teachings rejected a path of asceticism or renunciation and instead advocated a path of devotion while living in the world, emphasizing one’s responsibilities to family and community. The Guru practised what he preached. His marriage to Sulakhani, with whom he had two sons, was an important episode in his life as a householder. A Janam Sakhi painting shows the bride and groom in a festive setting with male and female family members, and a priest conducting the marriage rituals as appropriate in the Hindu custom (Fig. 3). What the painting does not show but other sources relate was Nanak’s regular questioning and rejection of rituals advocated by the Hindu priestly class (Brahmins), which he enacted at his wedding ceremony by not performing the prescribed number of ambulations around the consecrated fire. Such actions were seen at the time by some family members as acts of rebellion rather than of enlightenment.

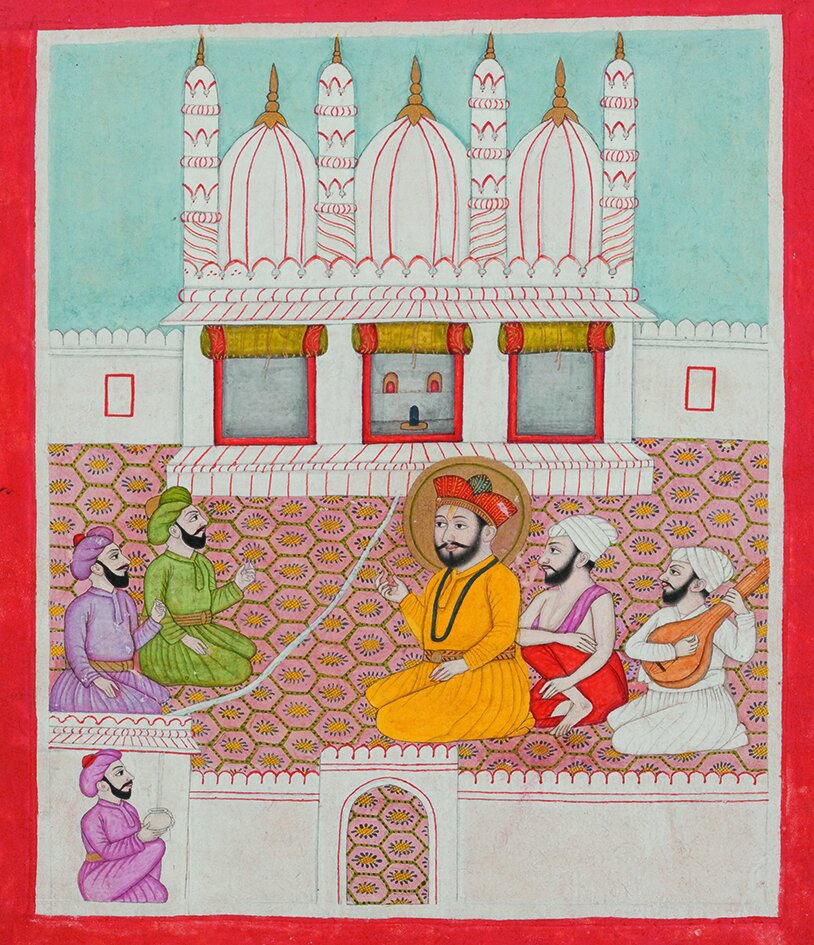

Guru Nanak began his ministry at the age of 30. He is said to have travelled widely both within India and beyond, visiting sites important to the various Indian belief systems and engaging in philosophical discussions with intellectuals, learning from them as well as teaching them. One episode describes Nanak’s visit to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city (Fig. 4). When Nanak lay down to rest here, he was chastised by the Muslim clerics for disrespecting God because his feet were pointing in the direction of the Ka’bah (considered by Muslims to be the House of God). In response, the Guru asked for the direction in which there was no God so he could move his feet accordingly, which rendered the clerics speechless. The painting shows Guru Nanak, identified by a halo of divine light, with his companions Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana, seated in a courtyard and conversing with the clerics. The location of a Muslim holy site is denoted by the domed building and minarets, typical architecture for shrines and congregational mosques in India. In place of prominence in the central window behind Nanak is a ‘black stone’. This key feature of the Ka’bah is here depicted as a lingam, the symbolic representation of the Hindu deity Shiva. The artist clearly had never visited Mecca or seen a picture of the cube-shaped Ka’bah with its black meteorite stone, and used the images familiar to him to interpret and imagine what he must have heard described. Such eclecticism marks not only the Sikh faith, but also its art.

Fig. 4 Guru Nanak and his Disciples Converse with Muslim Clerics, from a manuscript of the Janam Sakhis (Life Stories)

India, probably Murshidabad, West Bengal, c. 1750–1800

Opaque watercolour on paper, 20.3 x 17.1 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.58.22)

Fig. 5 Guru Gobind Singh

India, Punjab, c. 1830

Opaque watercolour on paper, 18.4 x 15.2 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.95)

Sikhism quickly attracted followers, mostly from the Punjab region’s farming and merchant communities, and Nanak’s message was continued by nine gurus who succeeded him. A few decades after his death in 1539, Nanak’s teachings were collected and preserved in the Adi Granth (or Guru Granth Sahib), Sikhism’s sacred text, which also includes hymns composed by the later gurus. In 1708, the tenth guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708) (Fig. 5) declared there would be no more human gurus after him; instead, the Adi Granth would serve as the Everlasting Guru. It is this scripture that remains at the centre of Sikh worship and ritual today.

The term ‘Sikh’ (Punjabi for ‘to learn’ or ‘to study’) refers to the primacy of study of the gurus’ teachings and sacred texts, and at the heart of Sikh worship is reading, listening to and chanting (kirtan) the Adi Granth. While Sikhs follow these practices in personal prayer spaces in their homes, the focus of communal religious life is the gurdwara. The first major temple was completed in 1601 at Amritsar (in today’s Punjab state, India). Originally called the Harmandir (‘Temple of God’), it is better known as the Golden Temple after the gilded decoration commissioned for its upper floors by Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839), and is Sikhism’s holiest site. From at least the mid-19th century on, the Golden Temple was perceived by European travellers as a major monument to be visited in North India, and was frequently represented in drawings and photographs (Fig. 6). It continues to be a much-visited place today, by Sikh pilgrims from around the world and others.

The exhibition’s second section is dedicated to the art of the Sikh kingdoms. If one were to think of a historical figure apart from Guru Nanak whose name has become near-synonymous with ‘Sikh’, it would be Maharaja Ranjit Singh. By the late 18th century, the Sikhs of the Punjab had organized into small political units, and in 1801 these were unified into a single powerful kingdom by the dynamic warrior Ranjit Singh, who established his capital at Lahore (in today’s Pakistan). Regional and international politics of the time (the weakening of the Mughal dynasty [1526–1858], the rise of the British colonial presence and incursions by the Afghans into India) placed Ranjit’s court in an important diplomatic position.

Fig. 6 The Golden Temple

India, Punjab, Amritsar, c. 1875–1900

Albumen silver print, 15.9 x 20.6 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

From the Collection of William K. Ehrenfeld, M. D. (2005.64.478)

British officials visiting the court described its magnificence and splendour in various historical sources. The Englishwoman Emily Eden (1797–1869), a guest at the Sikh court for several months in 1838 with her brother, who was the Governor-General of India from 1837 to 1842, spoke highly of Ranjit Singh’s hospitality and described in paintings and in writing some of the riches she saw. On 23 December 1838, she wrote: ‘The first show of the day was Runjeet’s [sic] private stud. [It] had on its emerald trappings, necklaces arranged on its neck, and between its ears, and in front of the saddle, two enormous emeralds, nearly two inches square, carved all over, and set in gold frames, like little looking-glasses. The crupper was all emeralds … Heera Singh said the whole was valued at 37 lacs [370,000 rupees]; but all these valuations are fanciful as nobody knows the worth of these enormous stones; they are never bought or sold … It reduces European magnificence to a very low pitch’ (Eden, 1867, p. 227). We see the horse and jewels in Eden’s work in Figure 7. The large diamond shown in two views (top centre) is the famous Koh-i-Noor, which then belonged to Ranjit Singh. This diamond—recut and significantly reduced in size—is today in the Tower of London, adorning the crown of the United Kingdom’s Queen Mother.

In contrast to the grandeur of his court, Eden and others commented on Ranjit Singh’s own simplicity of attire. W. G. Osborne, military secretary to the Governor-General, describing his first visit to Ranjit Singh wrote, ‘Cross-legged in a golden chair, dressed in simple white, wearing no ornaments but a single string of enormous pearls around the waist, and the celebrated Koh-y-nur [diamond] on his arm … sat the lion of Lahore’ (Osborne, 1840, p. 73). In the depiction of a court scene in Figure 8, Ranjit Singh is recognizable amongst the other noblemen only by subtle clues: his status is conveyed through the placement of his figure near the top and centre of the composition; he is at the front of the seating arrangement, with his sons behind or below him; and the standing figures approach Ranjit in a deferential pose with their hands clasped. The style of costume worn by most figures in the painting—the knee-length, white cotton tunics, distinctive robes, narrow-legged pants and colourful turbans—and their long, pointed beards identify them as Sikhs. While most figures here, including Ranjit Singh, are in left profile view, typical representations of Ranjit Singh show him from the right. He lost his left eye in a childhood bout of smallpox, and when represented in frontal or left profile view, he is usually shown with one eye closed.

Fig. 7 Ranjit Singh’s Favourite Horse and Some of his Finest Jewels, from ‘Portraits of the Princes and Peoples of India’

By Emily Eden (1797–1869), 1844

Hand-coloured chromolithograph on paper, 21.6 x 17.8 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.63.14)

Fig. 8 Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Members of his Court

India, Punjab, c. 1825

Opaque watercolour on paper, 19 x 23.5 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Gift of the Kapany Collection (1998.97)

Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839 left a power vacuum in the region, and his kingdom splintered into smaller polities. Taking advantage of this instability, the British fought two major wars against the Sikhs and in 1849 annexed all of Punjab to the British crown, sending Ranjit’s heir, the young Dalip Singh (1838–93), to England, where he spent most of his life. Under British rule, which had restored stability to the region, local Sikh rulers (now as ‘princes’ of the British Empire) developed public infrastructure and patronized a range of arts and music. Like other Indian royals, the Sikh maharajas of Jammu and Kashmir, Patiala, Kapurthala and Nabha among others variously negotiated their new identities as independent rulers of their own people while remaining under British overlordship. Aspects of such mediation are visible in portraits. In an official photography album commemorating King Edward VII’s (r. 1901–10) coronation celebrations held in Delhi in 1902–3, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir (left) and his brother (right) are seen combining European and Indian elements in their royal regalia: turbans and Indian-style swords are at home with European military uniforms, cloaks and gloves (Fig. 9). Such composite identities marked much of Indian culture during the 20th century, and not only for the Sikhs.

The Asian Art Museum’s exhibition closes with an illustrated timeline that gives an overview of Sikh history in California. The Sikhs were the earliest Indian immigrants to North America, having arrived on the West Coast in the early 1900s. Initially working to build railways and roads, many Sikhs settled in the agricultural heartland of California’s Central Valley, where large communities still remain. The US 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act brought in a new wave of highly educated Sikh professionals, and today Sikhs form an integral part of their local communities, occupying leading roles in politics, technology and other business sectors.

Fig. 9 Delhi Coronation Durbar 1st January 1903

By Wiele and Klein (act. from 1882)

Photographs (albumen prints) mounted on paper in leather-bound album, 39.1 x 46.4 cm

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

From the Collection of William K. Ehrenfeld, M. D. (2005.64.159)

Qamar Adamjee is Associate Curator of South Asian and Islamic Art at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

All images are © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Selected bibliography

Pardeep Singh Arshi, The Golden Temple: History, Art and Architecture, New Delhi, 1989.

Kerry Brown, Sikh Art and Literature, London and New York, 1999.

Emily Eden, Up the Country: Letters Written to her Sister from the Upper Provinces of India, London, 1867.

B. N. Goswamy, Piety and Splendour: Sikh Heritage in Art, New Delhi, 2000.

— and Caron Smith, I See No Stranger: Early Sikh Art and Devotion, Ocean Township, NJ, 2006.

Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer, Maharaja: The Splendour of India’s Royal Courts, London, 2009.

Gurinder Singh Mann, Sikhism, New Jersey, 2004.

W. H. McLeod, Guru Nanak and the Sikh Religion, Delhi, 1996.

Kamala E. Nayar and Jaswinder Singh Sandhu, The Socially Involved Renunciate: Guru Nanak’s Discourse to the Nath Yogis, Albany, 2007.

W. G. Osborne, The Court and Camp of Runjeet Sing, London, 1840.

Kavita Singh, New Insights into Sikh Art, Mumbai, 2003.

Susan Stronge, ‘Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Artistic Patronage at the Sikh Court’, South Asian Studies 22, no. 1 (2006): 89–101.

—, ed., The Arts of the Sikh Kingdoms, London, 1999.

This article first featured in our March/ April 2017 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.