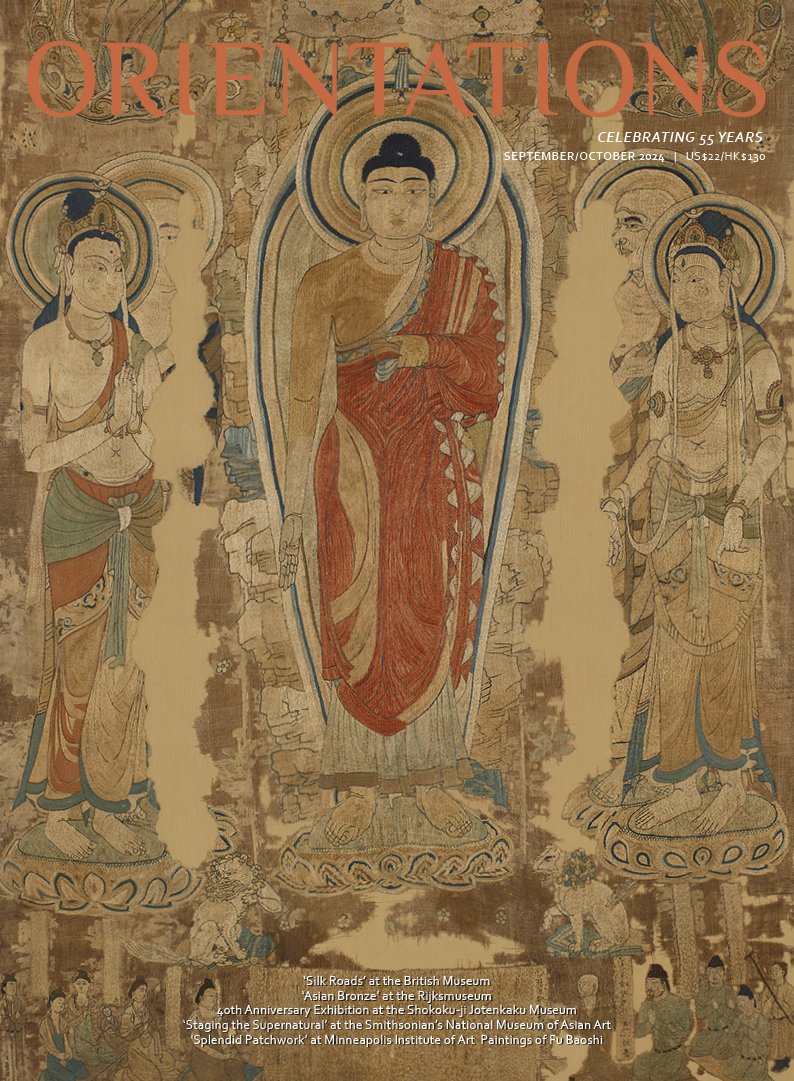

Staging the Supernatural: Ghosts and the Theatre in Japanese Prints

The exhibition ‘Staging the Supernatural: Ghosts and the Theater in Japanese Prints’ is currently on view in Washington, DC, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art (NMAA; 23 March–6 October 2024) (fig. 1). The origin of the exhibition dates back more than fifteen years but was buoyed into reality by two major acquisitions. The idea for a ghost-themed exhibition first came about while we were studying at the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Studies in Yokohama in 2009 and 2010. As fledgling graduate students suddenly thrust into an intense bubble of language and cultural training, we made a pledge to one day curate an exhibition together. Given the intersection of our interests, we decided the focus needed to be on ghosts and spirits. Almost a decade and a half later, we happily found ourselves working as curators at the same institution. As we made visits to the home of collector Pearl Moskowitz, our ideas began to resurface, gaining depth and texture through viewing the works in her collection. While spending hours in the sweltering summer of suburban Virginia, perusing ghost prints from the 19th and 20th centuries, we were captivated by her passion and the stories told and retold through the prints. Just as telling ghost stories became a summer pastime in Japan—the physical chills experienced by those hearing the stories’ frightening details provided a welcome coolness in the heat and humidity—viewing those prints provided a welcome relief from the stresses and uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The broad possibilities of a ghost-themed exhibition seemed endless, and much had already been done on this topic by museums in Japan and elsewhere, so we decided to concentrate on theatrical representations in print. Pearl’s collection, with its rich focus on ghosts on the stage, delivered an aperture onto ghosts as carriers of memory, examples of striking stage effects, and culturally significant stories. These narratives linked not only our world with the world beyond but also the past with the present. With the gift of the Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection to the NMAA in 2021, we suddenly had an incentive to make real that early idea of an exhibition about the supernatural, as it supplemented previous acquisitions given to NMAA by Anne van Biema (1915–2004) and Robert O. Muller (1911–2003) that contained many representations of supernatural subjects in kabuki. The subject of ghosts on the stage was further incentivized by a substantial collection of prints depicting the noh theatre by the artist Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927) that were given to NMAA by the Embassy of Japan in the 1970s. Kōgyo’s singular obsession with the noh theatre and its slow, eerie aesthetic offered both a striking counterpoint and a direct connector to the kabuki works in the Moskowitz collection.

1

View of entrance to the exhibition ‘Staging the Supernatural:

Ghosts and the Theater in Japanese Prints’, National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC (23 March–6 October 2024)

Photo by Colleen Dugan

2

Tsuchigumo, from the series Great Collection of Prints of Noh Plays (Nōga taikan)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1925–30

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 26 × 37.1 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

Despite the different dramatic styles of noh and kabuki, several major plays are common to both traditions. Tsuchigumo and Dōjōji are perhaps the two most powerful and well-known examples. They serve as much to connect the mediaeval noh with the early modern kabuki as they set the two forms of theatre apart. The noh play Tsuchigumo begins with the revelation that the protagonist Minamoto Yorimitsu (944–1021) has been struck by illness. No matter what remedy his retainers bring him, the sickness seems to persist, suggesting a more sinister cause. Yorimitsu ponders the meaning of life itself: ‘A person’s life is like foam on the water, disappearing here and gathering there’. Steeped in this fatalist mood, he strikes a conciliatory tone, saying that only he is to blame for his malaise—a hint that indeed something else is the cause for his suffering.

A strange monk soon reveals that an evil spider, the so-called ‘earth spider’ (tsuchigumo), has cast a spell over the warrior. It soon becomes clear that the monk himself is the earth spider in disguise, casting his poisonous net over Yorimitsu. This moment is shown in a print from Kōgyo’s last series of noh images (fig. 2). The paper net thrust from the hand of the actor is one of the most iconic examples of stagecraft in the noh theatre and imbues the play with a speed and sense of action not seen in many others. Yorimitsu’s retainer, Hitorimusha, later approaches the mound in which the earth spider resides and breaks it open. Just then, the spider appears and engages its enemies by shooting spiderwebs at them. Kōgyo captured that moment in prints from his One Hundred Noh Plays series (fig. 3). Though not actually shown onstage, the mound is faintly visible behind the earth spider, whose wild hair and elaborately coloured costume make for an imposing presence.

3

Tsuchigumo, from the series One Hundred Noh Plays (Nōgaku hyakuban)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1922–25

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.8 × 25.4 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

4

Dōjōji mae shite, from the series One Hundred Noh Plays (Nōgaku hyakuban)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1922–25

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.8 × 25.6 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, Robert O. Muller Collection

5

Dōjōji ato shite, from the series One Hundred Noh Plays (Nōgaku hyakuban)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1922–25

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.8 × 25.7 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, Gift of the Embassy of Japan, Washington, DC

In the noh theatre, the 15th century play Dōjōji is one of the most popular among the more than 200 plays that are known. The central element of this fast-paced play is a large temple bell; the play begins when the head priest enters the stage to relay that monks are about to consecrate it. Soon, a shirabyōshi dancer enters, wearing the courtier’s hat characteristic of this female-dominated performance art. As she is dancing, the monks are frightened by her crazed demeanor. In Kōgyo’s print, she approaches the bell, hinting that a past sin and unreciprocated love are weighing on her like the heavy temple bell (fig. 4). In the second part of the play Dōjōji, the dancer secretly slips underneath the temple bell before it drops over her. Frightened by the sound, the monks recount the tale of a woman who fell madly in love with a mountain priest but was abandoned by him. The priest hid underneath the bell as the woman turned into a fire-breathing demon and fried him by melting the bell. In the middle of the monks’ story, the dancer suddenly reemerges from underneath the bell in the form of a snake—the image illustrated in Kōgyo’s print. At the end of the play, the jealous spirit is quelled by prayer and burns herself with her own flames (fig. 5).

The kabuki incarnation of Dōjōji, first performed in 1753, shares the same essential plot with the noh version. In keeping with kabuki’s conventions for bombastic performances with dazzling sets and costumes, the kabuki version belongs to the stylized dance-transformation genre, hengemono. The central component of these plays is a dance sequence in which the same actor performs multiple roles, transforming between them during complex choreography. This is achieved through multilayered costumes that can be quickly removed or adjusted to reveal new sections. In an 1816 version of the play, the role of Kiyohime was played by Bandō Mitsugorō III (1775–1831) (fig. 6). With demonic features, the actor’s robes feature a tessellating diamond pattern that suggests the scales of a serpent. In the theatre, using pattern is a common strategy for providing clues to a character’s identity. For example, in kabuki versions of the tsuchigumo story, the earth spider eventually takes the form of Yorimitsu’s lover, Usugumo, whose name includes the character for ‘spider’ (fig. 7). If the verbal cue was not enough, the spiderweb pattern on her robe makes her true nature known to the audience.

6

Actor Bandō Mitsugorō III as the Maiden of Dōjōji

By Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865); 1816

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 36.3 × 25.6 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, The Anne van Biema Collection

12

Matsukaze, from the series One Hundred Noh Plays (Nōgaku hyakuban)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1922–25

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.8 × 25.7 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, Gift of the Embassy of Japan, Washington, DC

Aside from specific plays, a common thread that runs through many ghost narratives in both noh and kabuki is female revenge: women who have been wronged or abused and return as spectres to haunt their abusers. Perhaps the most famous ghost in Japanese pop culture is Oiwa, who was first brought to life on the kabuki stage in Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan (Ghost Stories of Yotsuya on the Tōkaidō), which debuted in Edo in 1825. Oiwa is horrifically disfigured by poison, given to her by a scheming neighbour who wishes to marry his granddaughter off to Oiwa’s treacherous husband, Iemon. Oiwa dies tragically, cursing Iemon’s name, but in the afterlife, she is eventually able to get her revenge against her evil husband and his associates. The more suffering that the mortal Oiwa endures, the more legitimate her vengeance becomes. In one memorable and harrowing scene, Oiwa attempts to comb her hair over the tumorous growth caused by the poison, but her hair begins to fall out in bloody clumps. The actor playing Oiwa, utilizing a pouch of synthetic blood hidden in a partial wig, squeezes blood onto the white paper of a toppled standing screen, the dripping sound amplified by a rhythmic drumbeat off-stage. Audiences then and now have been horrified and mesmerized by the sequence, which is represented in a number of prints (fig. 8).

The noh play Kanawa (‘iron crown’) is one of many featuring the vengeful spirit of a woman who was mistreated in her life. The play tells the story of a woman who describes her unforgiving feelings towards her former husband, who divorced her. She discloses how her love for her husband grows each day ‘like clothes I cannot shed’, and her deepest wish is for the deities to punish him. Eventually, her wish to become a demon and haunt her former husband is granted. She learns she is to don a red kimono and red makeup along with an iron crown with three candles. Kōgyo captures the moment the demon curses her former husband and promises to make those who harmed her suffer (fig. 9). The play is filled with twists and turns in the plot. Midway into the play, the woman begins to transform as the wind howls and thunder crashes. The scene then changes to focus on her former husband, who is plagued by nightmares. He seeks out the counsel of the great onmyō master Abe no Seimei (921–1005), who creates a prayer shelf with effigies meant to absorb the man’s torment. Kōgyo’s print shows the moment when the demon entered the bedroom of her former husband and beats the effigies—thinking they are him and his new wife—with her iron rod. The dark tension is palpable in the print.

7

Nakamura Shikan IV as Sakata Kintoki and Onoe Baikō (Kakunosuke) as Usui Sadamitsu (right); Sawamura Tanosuke III as Usugumo, Actually the Spirit of a Spider (Jitsu wa kumo no sei) (centre); Nakamura Chūtarō as Urabe no Suetake and Ichikawa Kuzō III as Watanabe no Tsuna (left)

By Utagawa Toyokuni IV (1823–80); 1864, 10th month

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 35.8 × 24.7 cm (each)

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

Both noh and kabuki rely on sophisticated stagecraft techniques. The special effects used in some kabuki ghost plays were unquestionably an enormous draw for audiences, such as the new effects that debuted with the production of Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan. Although a range of thrilling new effects were used, including the ‘hair-combing’ scene described earlier, one of the most well-known is the so-called ‘raindoor flip’ (toita gaeshi). In this sequence, the villain Iemon pulls a wooden door out of a river, only to find the corpses of two of his victims nailed to either side. What is especially remarkable in the performance is that both corpses are played by the same actor, who completes a quick costume and makeup change in order to appear as two different characters in rapid succession. On the stage, this was accomplished with the assistance of a hidden compartment behind the stage and the assistance of a stagehand. In prints, this feat was recreated in shikake-e, or trick pictures, where an additional piece of printed paper was glued along one edge and affixed to the print in a strategic location (fig. 10). When the flap of paper is lifted, a new detail is revealed—in this case, the tortured form of Iemon’s poisoned wife, Oiwa.

The Moskowitz collection also includes several rare works, including one unusually formatted diptych print illustrating the story of Kiyohime and the monk Seigen (fig. 11). Unlike the usual method of aligning diptych prints directly above or beside one another, this print is intended to be arranged in an offset configuration. The ghost of Seigen is pursuing his unrequited love, Kiyohime, as she runs through the night, her bare feet indicating the urgency of her escape. The appearance of a ghost was believed to be accompanied by a gust of wind, which can be indicated on stage through the use of a prop umbrella that turns inside-out at the click of a button. Kiyohime’s umbrella is inverted as she runs through the rain, and the diptych’s unusual format emphasizes the dynamic motion by creating a strong diagonal that follows the angle of the umbrella shaft. The artist of this split diptych, Jukōdō Yoshikuni (act. c. 1803–40), was an active member of the Osaka literary arts scene and was known as a poet and a singer of chants for the puppet theatre in addition to being a print designer. It was perhaps this background in various art forms that gave Yoshikuni the confidence to experiment with such an unusual compositional format.

8

Ōkawa Hachizō I as Oiwa and Ichikawa Sukejirō as Takuetsu in the play Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan

By Utagawa Hirosada (act. 1825–75); 1848

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 26.2 × 18.9 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

9

Kanawa, from the series One Hundred Noh Plays (Nōgaku hyakuban)

By Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927); 1922–25

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.8 × 25.7 cm

National Museum of Asian Art, Gift of the Embassy of Japan, Washington, DC

Noh is often considered an art of abstract gestures, stylized stage props, and allusive language chanted in a guttural timbre. These hints and allusions synthesize into a combination of expression and withholding. A good part of the core content of a play happens unseen, through clues and the audience filling in the gaps in their imagination. The chanting, singing, and dancing by the actors is often accompanied by a chorus and musical instruments, such as a flute and different-sized drums. Any music is as sparse as the stage props, serving only to underline critical moments or to build up tension during a play. The protagonist (shite), most often a spirit of a deceased person or a spectre linked with a place, puts on a carved wooden mask along with elaborate wigs and costumes that enable him not simply to act a part but also to effectively assume the very soul of a character. The actor becomes someone or something other than themselves.

As elaborate as the noh costumes are, as intricate yet reduced are the stage props. The paper spider webs discharged by the earth spider in the climax of Tsuchigumo are one of the most dynamic stage tricks in the entire noh repertoire. Most plays emphasize reduction over representation. The play Dōjōji is distinctive with its large bell as the de facto protagonist of the play. The bell is made of a bamboo lattice that is covered with cloth, making it light enough to be pulled up by two stagehands. Lattices covered in textile are the core components of many noh props, including the stylized salt wagon pulled by the salt-making sisters Matsukaze and Murasame (fig. 12). The angle of the protagonist’s mask and codified gestures serve to evoke specific associations. When Matsukaze lowers her head slightly and moves her flat hand to cover her face, any noh afficionado knows that she is crying. Unlike kabuki’s elaborate stage effects, noh relies on predictability and an audience’s ability to substitute the visible with the imagined.

10a

Seki Sanjūrō III as Naosuke Gonbei (right), Kataoka Nizaemon VIII as Tamiya Iemon and Bandō Hikosaburō V as the Ghost of Kobotoke Kohei (Kobotoke Kohei bōrei) (centre), and Bandō Hikosaburō V as Satō Yomoshichi (left)

By Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865); 1861, 7th month

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 37.5 × 25.4 cm (each)

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

10b (detail)

Kataoka Nizaemon VIII as Tamiya Iemon and Bandō Hikosaburō V as the Ghost of Oiwa (Oiwa no bōrei)

Throughout time and across the world, ghost stories have the ability to reflect widely held folk beliefs about the afterlife as well as deeply personal encounters with the supernatural. This exhibition enabled a similar dynamic for us: engaging the public with captivating and engaging theatrical narratives from Japan’s Edo period (1600–1868) and Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–26) eras, in addition to a personal story of developing an idea that took many years to come to fruition.

The exhibition is accompanied by the publication Staging the Supernatural: Ghosts and the Theater in Japanese Prints (Smithsonian Books, 2023). A specially created interactive feature is accessible on the exhibition’s website (https://asia.si.edu/whats-on/exhibitions/staging-the-supernatural/).

Kit Brooks is Curator of Asian Art, Princeton University Art Museum. Frank Feltens is Curator of Japanese Art, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution.

11

Nakamura Utaemon III as Seigen, Nakamura Karoku as Sakurahime, and Nakamura Daikichi as Tsutaki

By Jukōdō Yoshikuni (act. 1803–40?); 1814, 1st month

Woodblock print: ink and colour on paper; 38.1 × 25.4 cm (each)

National Museum of Asian Art, The Pearl and Seymour Moskowitz Collection

This article featured in our September/October 2024 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.