The Origins of Guyue Xuan Enamelled Glass Wares: A Documentary Group of Qing Imperial Enamels Produced in the Inner Palace between 1767 and the 1770s

Now that we know the origins of the name Guyue xuan, the date of its inauguration in 1767, the burst of production in a few months of summer/autumn of each year, and its place of manufacture in the Forbidden City, we are in a position to consider the objects’ purpose.

These clues suggest that they were produced initially as prizes to be distributed at the annual imperial hunting trip when, most years, the Qianlong court (1736–95) would move north of the Great Wall in either late September or October, by the western calendar. Based at Chengde (formerly Rehe or Jehol), a true summer palace, the hunt provided an excuse to train troops in the essential Manchu martial skills of archery and horsemanship. Apart from the emperor and members of his family, officials, and servants, the Manchu and Mongolian banners of the Eight Banner army were included—Han Chinese soldiers were not. The hunt provided an opportunity to reverse the effects among the Eight Banners of living a largely Chinese lifestyle in cities.

The hunt did not take place every year, but for the years of the dated Guyue xuan bottles under consideration here, from 1767 to 1770, it did. We know of the prevalence of such prizes from the imperial archives. It was noted that, in 1751 (sixth month, twenty-fourth day), a range of wares, including thirty unspecified snuff bottles, were delivered to be presented as prizes during the hunt and that in 1754 (first month, thirtieth day) the emperor ordered one hundred glass snuff bottles, in a variety of colours, to be prepared for use as gifts while hunting (Hui and Lam, 2000, p. 74). It was the emperor’s custom, while on hunting trips with his courtiers, to distribute gifts and prizes to successful hunters (archive no. 3449) (Hui and Lam, 2000, p. 56). In 1755 (sixth month, twenty-eighth day), an order was placed for five hundred glass snuff bottles and three thousand pieces of glass and utensils to be used as gifts at the palace at Chengde—the main base for the hunt (Brown and Raibner, 1987, p. 79; Brill, 1991, p. 144; Ho, 1995, p. xxiii). The predominance of snuff bottes among such prizes is due to the fact that the Manchus were snuff takers, following the lead of the Kangxi (r. 1662–1722) and subsequent emperors, and the snuff bottle—like the thumb ring, shaved forehead, and pigtail—became a Manchu national marker. Another archival entry in 1755 records that the Guangdong Maritime Customs Office submitted three hundred bottles of foreign snuff to be forwarded to the Court at Chengde. These would not have been snuff bottles as we use the term, but the large glass flasks in which imported snuff, much of it from Brazil, arrived in China.

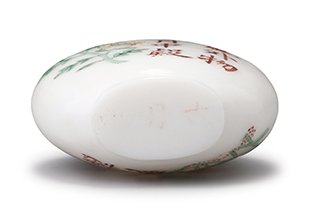

Fig. 1 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911),

Qianlong reign (1736–95), c. 1767–80

Painted enamel on glass; dimensions unknown

Private collection

In the 1751 record, wares for the hunt were delivered in the sixth month, and the majority of the dated Guyue xuan wares were also produced in the sixth month. Given those inscribed shangshang (first prize), it is reasonable to assume that Guyue xuan wares originated as prizes for the hunt. Most of the dated group are from the sixth month, with far fewer from the seventh. By the western calendar, the sixth month of 1767 was 26 June–25 July; in 1768, 14 July–11 August; and in 1769, 3 July–1 August. One exception is dated to the autumn of 1768. Autumn begins with the seventh month, which in 1767 began on 11 August by the western calendar, with the court leaving for the hunt over a month later, on 22 September. In other years, according to the Qianlong benji (Basic annals of Qianlong) the journey north was later (in 1767, 8 October; in 1769, 9 October; and in 1770, 14 October).

What appears to have happened in 1767 is that the emperor decided to set up a separate production centre for enamelled snuff bottles for distribution, not so much to advance the artistry as to provide gifts and prizes more efficiently. There was no need for the resulting objects to live up to the exacting and technically difficult demands of the finest Yuanming yuan (Summer Palace) wares. They needed little more than appropriately symbolic subject matter and some evidence of the imperial nature of the gift. To receive such a gift from the emperor was a sufficient honour; the nature of the gift itself was incidental. Large numbers of imperial bottles distributed as gifts during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) tended to end up in the tombs of the Qing elite. If one took a snuff bottle to the afterlife at all, it would of course be a bottle that represented the high honour of being singled out by the emperor. Some of the broad group of enamelled wares of this group have also been excavated from tombs (Fig. 1). It was advantageous for the court to avoid the expense and time involved in producing the finest enamelled glasswares, where the failure rate was relatively high, and instead produce much simpler wares more quickly and reliably. Those involved in the new, or re-opened, enamelling facility in the Forbidden City seemed to have started from scratch, with both artistically and technically rudimentary skills. We might also read some significance into the two most common subjects—the lotus, which grows in summer and autumn, and the chrysanthemum, firmly associated with autumn—but there is no need to do so to establish their period and purpose.

Because these objects are obviously not in a class with the finest enamelled-glass palace wares of the Qianlong period, they became suspect and have often been dismissed as later fakes. So far, research into the archives has yet to reveal any mention of Guyue xuan wares, but it is clear that not everything produced at the palace workshops was recorded. Thousands of glass snuff bottles were not, but we know by deduction that they were produced in large numbers because of records that hundreds of them were delivered to a stopper workshop and by recorded orders of stoppers for them.

Fig. 2 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), c. 1770s

Painted enamel on glass; height 5.8 cm, excluding stopper

Marakovic Collection, Vienna

Clearly much of the vast quantity of enamelled glass produced in imperial workshops was not considered in need of a detailed archival record. If Guyue xuan wares were initially made with little regard for their artistry, it is unlikely that they would have been recorded. A main focus of the archives was on what the emperor was personally interested in, ordered, and responded to rather than lower-level production in which he was not involved. Even masterpieces of enamelled glass were only occasionally recorded.

After the dated wares from 1767 to 1770, we begin to see growing sophistication in the painting and subject matter beginning in the 1770s. The Guyue xuan designation, mostly in iron red, migrated to the foot, while the style, subject matter, and limited palette of enamels remained much the same, although a frog sometimes appears with the lotus. The absence of any further precisely dated wares obscures the chronology of this evolution.

Fig. 3 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), c. 1770s

Painted enamel on glass; height 5.49 cm, excluding stopper

Formerly Mary and George Bloch Collection

One undated bottle, probably produced in the 1770s, is unusual not only in introducing panels of decoration and formalized surrounding designs but also in its engraved Guyue xuan mark—an occasional variant. A unique bottle from the gradually evolving early wares is stylistically similar, with the same lotus subject, but the glass has been carved in relief first, albeit in a rather unsophisticated manner (Fig. 2), heralding the later, relief-carved Guyue xuan wares. Another undated example, also probably from the 1770s (Fig. 3), shows a marked improvement and hints at the style of the classic Guyue xuan wares that followed, some of which were single-plane, with the enamelling going straight onto the flat glass surface, and others dual-plane, in which the glass had been previously carved in relief, with the main elements of the design to be completed by the enameller. Again, the poetic sentiment on one side refers to the ideal gentleman: ‘It [the lotus] stands upright, resembling the virtue of a noble man; it is unsullied, like the air cultivated by the ancients’.

On the dated wares the most common subject was the lotus, although some were decorated with chrysanthemums combined with text and the occasional butterfly. Together, the pictorial and textual elements offer auspicious symbolism suitable for general distribution to unidentified recipients. If the bottles were made for imperial consumption, the repetition of the same subject and general composition would have become tiresome, but if they were to be distributed always to different individuals, there was no need to vary the design. The lotus symbolizes peace, harmony, purity, and continuity. Lianlian (lotus-lotus), based on one name for the lotus, is a pun on niannian (year after year), suggesting that the recipient should strive for excellence in service to the emperor year after year. The natural and convincing wear of most examples, some so worn as to partially obliterate parts of the design, suggest considerable age and extensive use. This is to be expected of a gift from the emperor. The recipient would likely use it for the rest of his life, offering snuff to friends so they might enjoy both the content and the implications of the container.

Fig. 4 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), probably 1770–80

Painted enamel on glass; height 5.25 cm, excluding stopper

Formerly Mary and George Bloch Collection

This early documentary group then evolves steadily for the rest of the Qianlong reign. One distinctive group is associated with what is probably a pseudonym, Wu Yuchuan, usually signed in a seal, but in one example 玉川Yuchuan appears in regular script above the seal of the full name. The example on a blue ground (Fig. 4) obviously arises out of the early dated group. A series of imperial connections can be made with Wu Yuchuan wares through imperial designations or likely imperial subject matter. There is also one on imperial yellow glass, probably a product of the imperial glassworks (White, 1990, pl. 61). It is possible that the name first appears in the 1770s and may have continued into the abdication years, from 1796 to 1799, as some of the finest works bearing this name are inscribed on the foot 大清年製 Da Qing nian zhi (Made during the Qing dynasty). In the late 18th century, the only reason that suggests itself for such a usage is during the abdication years, when the Jiaqing emperor (1796–1820) was officially on the throne, but the Qianlong emperor still wielded overriding power and had his own reign title added to orders produced during the first years of the Jiaqing reign. The continued use of both reign marks on products is confirmed in the archives, but if these wares were still being used as prizes at the hunt, the more generic dynasty designation might have resolved a tricky protocol issue. After the first group of documentary wares, both the archives and the wares themselves fall silent. Indeed, after the early dated wares, we can no longer be sure which group was being made where. Between the 1770s and 1799, as the quality of both artistry and techniques improved, more skilled enamellers from the Forbidden City may have been transferred to the Yuanming yuan or carried on producing much-improved wares at the Inner Court facility.

Fig. 5 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), probably 1770–99

Painted enamel on glass; height 4.65 cm, excluding stopper

Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection

We can follow the evolution of the early dated group through the Wu Yuchuan wares to a series of wares with a broader palette, better quality of painting, and thin, painterly use of enamels (Fig. 5). Figure 6 was probably enamelled on an existing glass bottle already engraved with its reign mark; it represents the earlier phase of the classic Guyue xuan wares, beginning perhaps as early as the 1770s but probably continuing until 1799. It is possible that the use of the Guyue xuan designation continued for a while after the death of the Qianlong emperor, even if his reign title did not. The reign name was not used apocryphally until the development of antiquarian interest in old snuff bottles from the early Daoguang period (early 19th century). Figure 7 is typical of the best of the single-plane Guyue xuan wares, which probably evolved into the dual-plane equivalents that would then have continued as a parallel option thereafter, rather than as a replacement. Figure 8 represents the highest level the two-plane group.

Fig. 6 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911),

Qianlong reign (1736–95), c. 1770s–99

Painted enamel on glass; height 5.4 cm, excluding stopper

Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection

By the end of the 18th century it becomes more difficult to separate out distinct groups. Figure 9 is an example in which the jewel-like quality of the enamels is inherited from mid-reign masterpieces from the Yuanming yuan workshop, but the bottle has the standard Guyue xuan designation on the foot. In this case, however, by comparison with enamelled metalwares, we can date this subject and the general composition of pairs of birds to the latter years of the Qianlong emperor’s life. There are two known versions enamelled on metal from the abdication years of 1795 to 1799, one marked嘉慶御製Jiaqing yuzhi (Made by imperial command of the Jiaqing emperor) and the other 乾隆御製 Qianlong yuzhi (Made by Imperial command of the Qianlong Emperor), both probably painted at the same time, one for each emperor. The design and composition may, of course, predate these two bottles, but it does establish the theme as still current in the abdication years, even if this particular bottle may have been made earlier at either workshop. There are equivalents of some of these groups in wares other than snuff bottles (vases, water vessels, and a lone thumb ring), although the Wu Yuchuan, wares are confined to snuff bottles. With the broader range of vessels, either the Guyue xuan or Qianlong four-character regular-script marks appear on the foot.

Fig. 7 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Painted enamel on glass; height 5.64 cm

Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection

Contradicting the common attribution of some of these wares to the Republic period (1912–49), one of the undated bottles, from the broader group but stylistically attributable to 1767–80, was recently excavated from a tomb near Beijing in a condition that suggests lengthy interment (Fig. 1). It is painted on a transparent green glass bottle of a type reasonably associated with imperial production and bears an iron-red, four-character Qianlong reign mark. It also has an original 18th-century-style metal stopper, corroded from long burial. Such examples are also found in early collections. One in the Victoria and Albert Museum was part of the Salting Bequest of 1910, while the above-mentioned yellow ground example, signed with the name Wu Yuchuan, was given to the V&A in 1916 as part of the Orchardson gift (White, 1990, pl. 60). The signs of wear suggest considerable use that the object was highly unlikely to have experienced in the four years between when the Republic period began and when it entered the museum’s collection.

The question mark hanging over the group arose because it had become firmly established that enamelling on glass reached a far higher standard of technical and artistic perfection at the court well before the term Guyue xuan was introduced to the art. It seemed sensible to be cautious about a later imperial group that was, by comparison, artistically pedestrian. The debate over the imperial origin of these works is the subject of the third and final part of this article.

Fig. 8 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Painted enamel on glass; height 6.6 cm, excluding stopper

Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection

Fig. 9 Guyue xuan snuff bottle

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), late Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Painted enamel on glass; height 6.8 cm, excluding stopper

Water, Pine and Stone Retreat Collection

Hugh Moss is a collector, author, and artist.

Selected bibliography

Robert H. Brill and John H. Martin, eds, Scientific Research in Early Chinese Glass, Corning, 1991.

Claudia Brown and Donald Raibner, The Robert H. Clague Collection: Chinese Glass of the Qing Dynasty,

1644–1911, Phoenix, 1987.

Kam-chuen Ho, Chinese Snuff Bottles: A Miniature Art from the Collection of Mary and George Bloch, Hong Kong Museum of Art, 18 March–8 June 1994, Hong Kong, 1994.

Humphrey K. F. Hui and Peter Y. K. Lam, Elegance and Radiance: Grandeur in Qing Glass: The Andrew K. F. Lee Collection, Hong Kong, 2000.

Helen White, Snuff Bottles from China: The Victoria and Albert Museum Collection, London, 1990.

This article first featured in our March/ April 2023 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.