The Vohemar Necropolis, Madagascar, and the Regional Distribution of Chinese Ceramics in the Swahili World (13th–17th century)

The port of Vohemar is located on the northeastern coast of Madagascar, facing the Maldives archipelago and the southern part of the Indian peninsula. The town’s necropolis, hidden today by dense, newly built construction, is located exactly at 13°21’ S and 50°00’ E (Fig. 1). This remarkable site was described by European explorers early in the second half of the 19th century. It was later excavated several times in successive digs from 1899 and throughout the first half of the 20th century by French amateur archaeologists (who were civil servants, doctors, and priests). Among them, the most famous are A. Grandidier (1836–1921), A. Maurein, P. Gaudebout, C. Poirier, E. Vernier, J. Millot, and S. Raharijaona. The 1971 publication in France of a report containing the most important excavations carried out by E. Vernier and J. Millot in the mid-20th century sparked unprecedented interest in the study of the necropolis. This work was subsequently carried out by Malagasy and French academics and curators. Since 2000, major innovative and multidisciplinary research has once again been undertaken by Malagasy, French, Swiss, Dutch, and Chinese scholars, making the Vohemar necropolis the most representative and the best studied site of the Rasikajy culture.

The Vohemar necropolis is one of the rare burial sites in eastern Africa that has been thoroughly excavated, though we now regret the lack of scientific rigor and coherent archaeological records. In total, more than 600 tombs have been uncovered. The construction and materials of these tombs are of good quality, such as stone or composite material mixed with sand or crushed coral. They are oriented from west to east, with the body of the deceased turned towards the east and their face towards the north (toward Mecca). More than half of these 600 excavated tombs are more or less richly furnished with funerary objects. The number of objects varies significantly, ranging from three or four pieces to a dozen, sometimes even twenty or so for the more opulent tombs. The objects were found laid out in the same way inside the tombs: bowls, dishes, and spoons were placed on or around the upper half of the body, a bronze mirror on the forehead, and a soapstone tripod by the feet.

Fig. 1 Map showing the location of Vohemar, at the western edge of the Indian Ocean

Photo © Bing Zhao

Archaeological artefacts unearthed from the Vohemar necropolis, mainly consisting of funerary objects, are currently kept both in France (the Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris and the Museum of Natural History in Nîmes) and in Madagascar (the Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Antananarivo). They constitute an exceptional array of perfectly preserved objects: weapons (swords), iron tools (needles, daggers, knives, and scissors), everyday utensils (ceramic jars, ceramic bowls, glass bottles, and spoons of mother-of-pearl), and ornaments (bronze mirrors; agate and glass-bead necklaces; silver and glass-bead bracelets; and gold, silver, bronze, and agate rings). It is important to highlight the staggering number of well-identified imported items among these funerary objects. Along with Chinese ceramics, which are the most numerous, there is Islamic glassware, Indo-Pacific glass beads, bronze mirrors (probably of Islamic origin), and Indian and southeastern Asian gold or silver jewellery. These imported goods testify to the incredibly cosmopolitan nature of the so-called Rasikajy society, a cultural phenomenon shared with almost all Swahili ports.

The Swahili world corresponds geographically to a narrow corridor of land, sea, and small islands about 2,500 kilometres in length, stretching from Somalia to Mozambique on the eastern coast of Africa, including the Comoros islands and northern Madagascar. The progressive Islamization of eastern Africa, from the 8th century onwards, went hand in hand with the expansion of long-distance trade in the region. In parallel, the Rasikajy culture first appeared on the estuaries of several rivers along the northeastern coast of Madagascar. Recent DNA research on the deceased of the Vohemar necropolis has furthermore attested possible contacts between Madagascar and southeastern Asia beginning as early as the 9th century . From the 8th to the 15th century , benefiting from the geographical location at the crossroads of several maritime routes and the natural richness of the hinterland, the inhabitants of this coastal community explored a type of ultramafic metasomatic soft stone for the production of tripod vessels. The distribution of these vessels extended into eastern and northern Africa, the Arabian peninsula, the Persian Gulf, and as far away as southern and southeastern Asia.

Fig. 2 Large dish with freely carved floral pattern in the centre

China, Longquan kilns; latter half of the 14th century–early 15th century

Green-glazed porcelain; diameter 34.5 cm

Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris, France

Photo © Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac

Fig. 3 Dish with flat rim and a pair of stamped fishes in the centre

China, Longquan kilns; mid-to-latter 13th century

Green-glazed porcelain; diameter 14.5 cm

Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Nîmes, France

Photo © Bing Zhao

The Chinese ceramics excavated from the Vohemar necropolis form a remarkable collection, mainly constituted by entire pieces. It is interesting to note that some Chinese porcelain dishes were split in two before being placed in the tomb, presumably to help the soul of the deceased to escape. However, they are archaeologically complete (Fig. 2). Chinese ceramic sherds have been found from about 100 archaeological sites in eastern Africa. However, in general terms, there are no or very few intact pieces of Chinese ceramic found in archaeological contexts in eastern Africa. The case of the Vohemar necropolis is therefore unique in the Swahili world as well as the Indian Ocean region. Furthermore, the excavation of burial sites is forbidden in Muslim countries. In fact, tombs in eastern Africa were rarely furnished with funerary objects, and the few tombs that did contain such objects have often been looted or vandalized, beginning in the 19th century.

The corpus of some 200 Chinese ceramics from the Vohemar site is composed of two main categories: green-glazed ceramics from the Longquan kiln complex in Zhejiang and blue-and-white porcelain from the Jingdezhen kiln complex in Jiangxi. Other categories are represented in smaller quantities, such as very small fragments of Qingbai ware, white porcelain, overglazed-red and -green enamelled ceramics, and fahua-glazed stoneware. The dating of the Chinese ceramics unearthed at the necropolis seems to indicate that the port of Vohemar was actively involved in long-distance trade from at least the mid-13th century until the early 17th century, with its peak period from the last quarter of the 15th century to the beginning of the 17th century.

Fig. 4 Large dish with freely carved floral pattern in the centre

China, Longquan kilns; latter half of the 14th century–early 15th century

Green-glazed porcelain; diameter 35.5 cm

Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Nîmes, France

Photo © Bing Zhao

Among the green-glazed ceramics from Longquan, the earliest pieces constitute dishes with shallow sides and flat everted rims in small sizes (with mouth diameters under 15 centimetres). Among them, we can find the well-known ‘double fish’ dishes, which are decorated by a pair of appliqued or stamped fish in the centres and can be safely dated to the middle and the latter half of the 13th century, by referring to Chinese archaeological discoveries in the kiln sites and in consumption sites, particularly tombs (Fig. 3). The example conserved at the Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris bears a badly fired yellowish glaze. Other high-quality contemporary green-glazed ceramics from Longquan consist of dishes with rounded sides decorated with a stamped floral pattern under a thick and homogeneous green glaze. The bases and foot rings are covered by the glaze except for the unglazed parts, which turned red during firing (Fig. 4).

During the first half of the 13th century, many western Asian merchants fleeing Mongol attacks went to Syria, Egypt, Yemen, and India, leading to a complete reconfiguration of the maritime networks in the western Indian Ocean. Quantitatively, Chinese ceramics in the western and eastern Indian Ocean increased significantly from the second half of the 13th century onwards as well as in the Swahili world and in the Red Sea area. The presence of Chinese ceramics found in archaeological sites in the Maldives archipelago offer material evidence of the appearance of a new regional network: the Maldives islands gradually became an alternative route for Chinese ceramics destined for eastern Africa during the 13th and 14th centuries. It should be noted that throughout the 14th century, maritime trade between India, southeastern Asia, and China continued, despite a decline in trade in the western Indian Ocean. In addition, from the second quarter of the 15th century, India’s Muslim nakhudha emerged as powerful players in the wake of the new states rising from the ruins of the Delhi sultanate. This southern Asian dynamic contributed to the development of regional emporiums in northeastern Madagascar. In other words, the Rasikajy culture’s period of prosperity was closely tied to the interregional developments that took place between eastern Africa, southern Asia, and Madagascar from the mid-13th century onwards.

Fig. 5 Bowl with everted sides and everted rim

China, Jingdezhen kilns; late 15th–early 16th century

Blue-and-white porcelain; diameter 15 cm

Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Nîmes, France

Photo © Bing Zhao

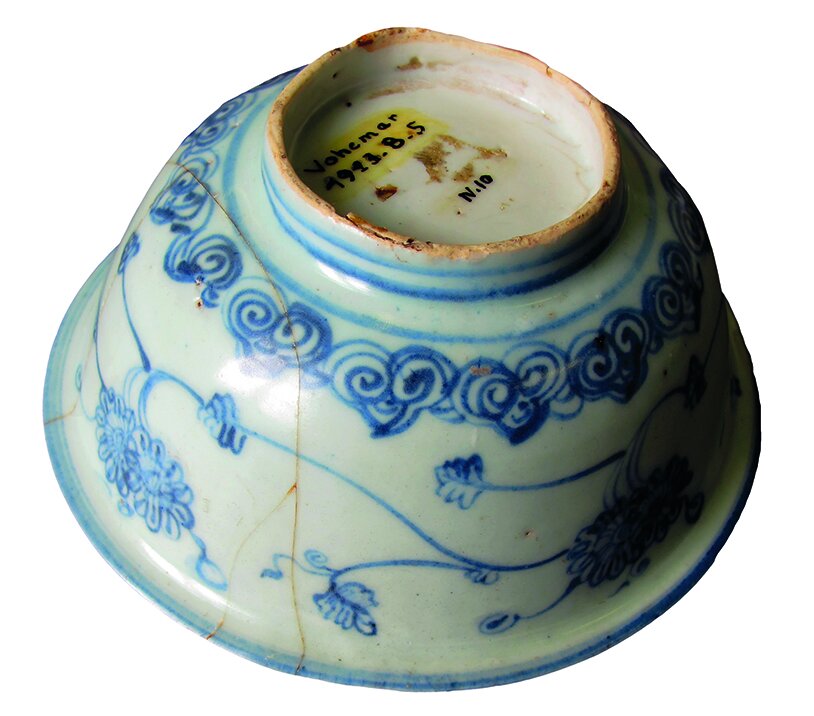

Fig. 6 Bowl

China, Jingdezhen kilns; 17th century

Porcelain with craquelled greyish glaze; diameter 8 cm

Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris, France

Photo © Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac

The 14th and 15th century high-quality, green-glazed ceramics from Longquan found in Vohemar include exclusively large dishes with rounded sides (with mouth diameters exceeding 30 centimetres). The centres of these dishes bear richly carved or moulded floral patterns (see Fig. 4). From the mid-13th century, green-glazed ceramics from Longquan and their imitations from Fujian were imported into eastern Africa in increasing quantity. This increase in the volume of Chinese ceramics was one of the causes of the 14th century decline of the Iranian industry in sgraffito, a luxury glazed Islamic ceramic widely traded in the Indian Ocean from the 10th to 13th century. In the Swahili world from the 13th century onwards, Chinese ceramics appear to have been intentionally valorized in various ritual contexts, such as public ceremonies, feasts, and funerary trends. The large richly decorated dishes of green-glazed ceramic from Longquan appear to have played an important role with other ostentatious tableware like Islamic glazed ceramics and beautifully crafted African pottery. Chinese ceramics, as well as other associated objects related to social practices, would have played an important role in the transmission of the collective memory in the Swahili city states. Furthermore, from the end of the 13th century, green-glazed dishes and bowls or blue-and-white porcelain were inserted in the façades of pillar and dome tombs, which were funerary structures reserved for the elite. Thus, the ownership of these exotic objects in the Swahili world was apparently linked to the members of the elite social class that took part in long-distance trade.

The second main category of Chinese ceramics from Vohemar consists of blue-and-white porcelain from the Jingdezhen kiln complex. This blue-and-white porcelain represents a type of hybrid object, resulting from multiple exchanges between China and the Islamic world involving mutual appropriation and the imitation of styles and techniques. Chinese sources and physico-chemical analyses confirm, moreover, that the first Chinese ‘blue-and-white’ was produced with Persian cobalt, presumably imported by Muslim merchants living in Quanzhou. Chinese researchers even support the hypothesis that ‘Persian’ craftsmen from greater Kashan in Iran were involved in production in Jingdezhen kilns in the 1330s. Blue-and-white porcelain in the 14th century, along with underglazed copper-red porcelain, was exported to eastern Africa on a limited scale, its volume increasing from the 1460s onwards. Small sherds of blue-and-white porcelain from the 14th century have been recorded as excavated from Vohemar. While the blue-and-white porcelains that are entire pieces from Vohemar are all datable to after the 1460s, their quality is clearly inferior when compared to the 15th century green-glazed ceramics from Longquan. This group is composed of bowls and dishes, all of small sizes, decorated with Chinese manganese-rich dark-cobalt designs under a transparent bluish glaze (Figs 5, 6, 8). The more frequently found items from the Vohemar necropolis, defective blue-and-white porcelain vessels from the 15th and 16th centuries, attest to the absence of quality control in the illicit private trade of Chinese ceramics from the 1460s onwards.

Fig. 7 Dish with qiling in the centre

China, Jingdezhen kilns; early 16th century

Blue-and-white porcelain; diameter 20 cm

Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Nîmes, France

Photo © Bing Zhao

Fig. 8 Bowl with everted rim

China, Jingdezhen kilns; latter half of the 16th century

Blue-and-white porcelain; diameter 14 cm

Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Nîmes, France

Photo © Bing Zhao

A large quantity of the Chinese ceramics in the Vohemar necropolis date from the early 16th century to the early 17th century (Figs 6–9). During this period, when the Portuguese were heavily involved in trading in the area, the markets of the Muslim world were still the engine that drove the Chinese porcelain industry. Generally speaking, in terms of the composition of Chinese ceramics imported to the Indian Ocean region, the Portuguese period marks a significant change. First of all, the wide range of southern Asian wares that had been imported from the 14th century onwards almost completely disappears (especially during the 15th century, when imports from China increased). Only large black-glazed stoneware jars from Twante in the Yangon region in Myanmar and Vietnamese blue-and-white porcelain continued to circulate in the 16th and 17th centuries. As for the Chinese ceramics, the type of imports is reduced to predominantly blue-and-white porcelain from Jingdezhen. Blue-and-white porcelain from Jingdezhen began arriving in the Middle East and Africa as early as the mid-14th century. Its trade volume began to increase from the 1480s onwards, and it eventually became the primary component of the trade in the early 16th century, alongside a very small quantity of monochrome porcelain (white, blue, and yellow) and porcelain with overglaze painted enamels. Longquan green-glazed ceramics and their imitations from southern China, which had represented the bulk of Chinese exports until the end of the 15th century, gradually disappeared.

Indeed, the Portuguese State of India brought upheaval to the Indian Ocean and the annexed seas because no power had tried previously to control the various trade networks that had been coexisting for centuries in an equilibrium, however fragile and ever-changing. Yet, while the assertion of Lusitanian power was pivotal, we must take into account the almost simultaneous emergence of two Asian empires: the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) in Iran and the Ottoman empire (1299–1922) in Turkey. The Chinese ceramics trade in the Indian Ocean in the 16th century, over which the Portuguese now had a monopoly, is an excellent illustration of this global trade of ‘indirect control’, which relied on existing regional and local distribution networks. In concrete terms, the actors involved were civilians or military officials operating on their own accord, and this was even more true after Portugal came under the rule of the Spanish crown in 1580. In eastern Africa especially, this dual mode of trade, both official and private, was organized through the Lusitanian ‘shadow empire’ and the network of Portuguese colonists, acting independently from the Portuguese court. These communities, although few in number, were very active in the regional, non-major maritime routes and also in trade with local merchants. It is likely that they used the route linking southern India to northern Madagascar, which had previously been used by merchants from southern Asia from the 13th to the 15th century. The 16th and 17th century Chinese ceramics from the Vohemar necropolis, therefore, attest to the ‘private’ spatial deployment of Portuguese power in Madagascar. The study of these underlying networks is all the more important because it relativizes the vision of a 16th century monolithic European global trade in the Indian Ocean, and it allows for a better understanding of the plurality of regional networks involved in the long-distance maritime trade at the time.

Fig. 9 Jarlet

China, Zhangzhou kilns; latter half of the 16th–early 17th century

Fahua-glazed stoneware; height 9 cm

Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris, France

Photo © Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac

Bing Zhao is Research Director of the East Asian Civilizations Research Centre (French National Centre for Scientific Research), an archaeologist, and a historian of techniques. Her research focuses on the circulation of Chinese ceramics and enamel wares beyond the Chinese territory and on the mutual influences of related manufacturing techniques between China and the Islamic world as well as between China and Europe.

Selected bibliography

Christoph Nitsche, Guido Schreurs, and Vincent Serneels, ‘The Enigmatic Softstone Vessels of Northern Madagascar: Petrological Investigations of a Medieval Quarry’, Journal of Field Archaeology 48, no. 1 (2023): 55–72.

R. L. Pouwels, ‘Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1880: Reviewing Relations in Historical Perspective’, International Journal of African Historical Studies 35, nos. 2–3 (2002): 385–425.

Pierre Vérin, The History of Civilization in North Madagascar, Rotterdam, 1986.

Elie Vernier and Jacques Millot, Archéologie malgache: comptoirs musulmans, Paris, 1971.

Bing Zhao, ‘La céramique chinoise et de l’Asie du Sud-Est du site de Vohémar à Madagascar: vers une datation plus fine et une approche plus historique’, Études de l’Océan Indien 46–47 (2012): 91–103.

This article first featured in our March/ April 2023 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.