A Battlefield of Judgements: Ai Weiwei as Collector

A celebrity of our times, Ai Weiwei (b. 1957)—influential contemporary artist, filmmaker, photographer, writer, curator, architect and oft-labelled ‘activist’—was voted ‘most powerful person in the art world’ according to ArtReview in 2011, shortly after he was secretly detained for 81 days by Chinese authorities. Upon his release, Ai was accused of tax evasion and fined RMB15 million (approximately US$2.4 million). His passport was confiscated and he was put under surveillance at his studio home base in the Beijing arts district of Caochangdi. If these sanctions were the Chinese government’s attempt at curbing his influence, they backfired: Ai has only become more popular as a leading cultural figure and an avatar of social criticism and free expression both in China and abroad. In the last four years, his artwork has been featured in more than fifty international shows, including a recent exhibition on Alcatraz Island, and a current retrospective at the Royal Academy of Art in London.

One wonders, however, whether this artist is not best known for the wrong reasons. Ai Weiwei, son of the celebrated modern poet Ai Qing (1910–96), has a side that is often overlooked. This larger-than-life figure is one of the most passionate collectors and connoisseurs of Chinese antiquities, particularly jade, that I have met. In fact, he financed much of his early work as a contemporary artist through the sale of antiques, and if one examines his output through the lens of the art historian, it is easy to see how most of his oeuvre tends to be a playful re-interpretation of traditional materials or a staged intervention with historical objects. In July 2015, the morning before Ai received his passport back from the Chinese authorities, we had a unique chance to talk about his past and his passion for antiquities:

Tiffany Wai-Ying Beres First, we should get the formalities out of the way … how long have you been reading Orientations?

Ai Weiwei The first time I picked up the magazine I was in New York in the early ’90s. I realized right away that this was probably the most precious material published on Asian art. In Chinese we have the magazines Wenwu and Kaogu, but there were no colour prints.

TWB So when you were in New York, you were already interested in antiques?

AWW I wasn’t collecting at all, but I was starting to read. At the time, I never thought about collecting Chinese things because I was poor. This was right before I moved back to China [in 1993]. I had a day job to support myself, and I didn’t imagine that I could use the money I made in the US to buy antiques in China.

Ai Qing’s jade seal

TWB How did your love for old things begin?

AWW I have [always had] a deep love for old things, things from the past, but grew up in a society that encouraged the destruction of the past: anything old should be destroyed because it reflects feudalism, capitalism or imperialism … something like that, a kind of brainwashed mentality.

I was kind of lucky because my father did have some collections, particularly ink paintings—he was friends with Qi Baishi, Huang Binhong, and Lin Fengmian—all these people. He had studied [painting] in Hangzhou, and Lin Fengmian, who was the [Chinese Academy of Art] principal at the time, encouraged him to go to France. He loved old things and appreciated beauty. Even during the difficult times [of the Communist Revolution period] my father still continued to collect a lot of stuff. Of course, most of his collections got lost during this period, but these objects remained in my mind while I was growing up. In Xinjiang [where the Ai family was exiled in 1959, and where Ai Qing was forced to do hard labour such as cleaning the village toilets], those objects were the most beautiful elements in our life.

TWB So when did you begin collecting?

AWW Even before I came back to China I was thinking: ‘What am I going to do when I go back?’ At that time there was not much going on in contemporary art because it was still very tight after ’89, so I started paying attention to the past. My younger brother Ai Dan loves antiques. The day I landed, he took me to Huangcungen, an area in Beijing with a lot of antique shops. The shopkeepers were just sleeping in their stalls with nothing to do. I noticed some hardwood furniture in the market that had been taken apart and kept as a bundle. No one was paying any attention to it so I asked: ‘How much?’ 100 kuai. I was so surprised; this was rosewood furniture! I wondered how a whole society could not recognize the value of something so precious. So I started to visit the market every day.

At the beginning I was very interested in bronze belt buckles [daigou], and other things like early Wei or Qi dynasty Buddhist sculpture in stone. At that time nobody wanted those things. The market at that point was still shaped by post-Qing dynasty style: what Westerners were collecting like late Qing porcelain, Tang dynasty horses or court ladies, or early bronze with inscriptions. These things were already widely featured in the Western market so they were quite a bit more expensive. In China itself there was no established market. Taiwanese people might come to buy, but they were focusing on things in the auction catalogues. Other items such as archaic jades and early pottery were not expensive, so I was drawn to this ocean of material.

Furniture, jade, bronze, silk—I fell in love with all these materials. As an artist, I think I appreciated their craftsmanship. I became well known among the shop owners. Most people would go there for things that they could quickly buy and make business. I was interested in things people didn’t want—curiosities, bones, games, things that people couldn’t identify.

TWB Today the antique markets in China are not just crowded with collectors; they are also filled with fakes. How did you become an expert?

AWW At the beginning of the ’90s all the dealers had plenty of real pieces so they didn’t bother making fake ones. It really was a golden time. Every day I would go to the market and get a handful of objects, come back home, wash them, take care of them. My mom even felt kind of jealous. She would say: ‘How come my son pays more attention to these old things than to me. He comes back from the United States, he doesn’t have a steady job, and he doesn’t pay attention to anything else but his antiques—he must be crazy.’ But for me, it was like being in love, it was irresistible.

Of course, after a while, I also made business out of this love. I had accumulated so much, and over time my interests changed, so I began to sell. I also realized that only by selling something was I able to test my own judgement. So over time, I started to buy better things, but of course the market itself also got higher and higher. Still, there were many things that people undervalued. When I started I was looking at things no one cared about; later, these items turned into very hot items in the market.

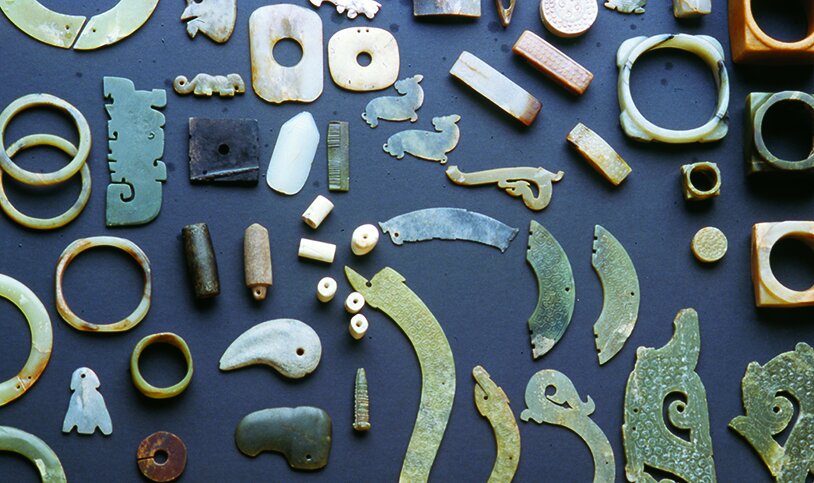

Jades from Ai Weiwei’s collection, 1994

TWB Can you tell me more about your collection?

AWW I would say I love jade. Jade has such a long history and it is also very difficult to learn about. Many dealers have an easier time getting to know other materials, but jade requires true connoisseurship. Jade is the longest-existing and evolving art in China; it reflects every dynasty’s ideas and their technical ability to make it. I have over a thousand pieces of jade. The problem is that I have never really put them in order. Even this morning I was looking at several pieces but they can be difficult to find because they are so messy. I have to make boxes, but I hate boxes because they take up so much space, they are heavy and cumbersome. I have just been using plastic bags, which are easier to find and look through. It’s a little bit like those dealers who tote plastic bags for drugs (laughs). But seriously, I need to make some kind of box to pay some respect to my jades. Boxes may not be user-friendly, but will give them a sense of dignity.

TWB Is your goal to have an encyclopaedic collection of jade?

AWW From the very beginning, I was fascinated with early jade from the Neolithic times, such as those objects from the Liangzhu and Longshan, the forms themselves are so attractive … the texture, patina, everything—it’s fascinating! Of course, later, I began paying attention to the entire development of jade in China from the Neolithic to the Qing dynasty. I never paid much attention to Ming or Qing jades though, because by these later periods the forms became more like decoration. But Liao or Yuan dynasty jades are very interesting; they can be very tricky because these were periods in which foreign rulers were in China, so many objects have a very different flavouring. Still, I have to say that my true love is jade from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. At that time jade served not as decoration but as a ritual object; it had a spiritual purpose, to communicate between heaven and earth.

TWB Xinjiang is also known for its white jade (hetianyu). Did you come across this jade when you were living there?

AWW In Xinjiang my experience was more like being a prisoner than anything else. I had never even heard the word hetianyu, but I had seen one: my father had a jade seal, a very nice piece of hetianyu that had been carved with the characters: 唐훠켄唐濟 (you rennai you ji), which translates as: ‘If you can endure then there’s a way.’ He was frightened because he knew that if the authorities found that seal he would be punished, if not killed, so he tried to grind down the characters on it with sandpaper. But because the jade is so hard, the words never disappeared. To me that piece of jade was just so powerful—it was dangerous: time and man could not destroy it. I still have that piece.

TWB What is the goal for your collection?

AWW Maybe this is the most fascinating part because, as a collector, you know these pieces don’t really belong to you. Of course, it is also possible to donate them to somebody, but then you have to trust that person or that institution, right? So it is a difficult decision. For me, these pieces are part of who I am, but who will take care of them after I am gone? Very often you see collectors whose family do not care about their collections, and once they are gone these collections just get broken up and sold; this is very sad to see.

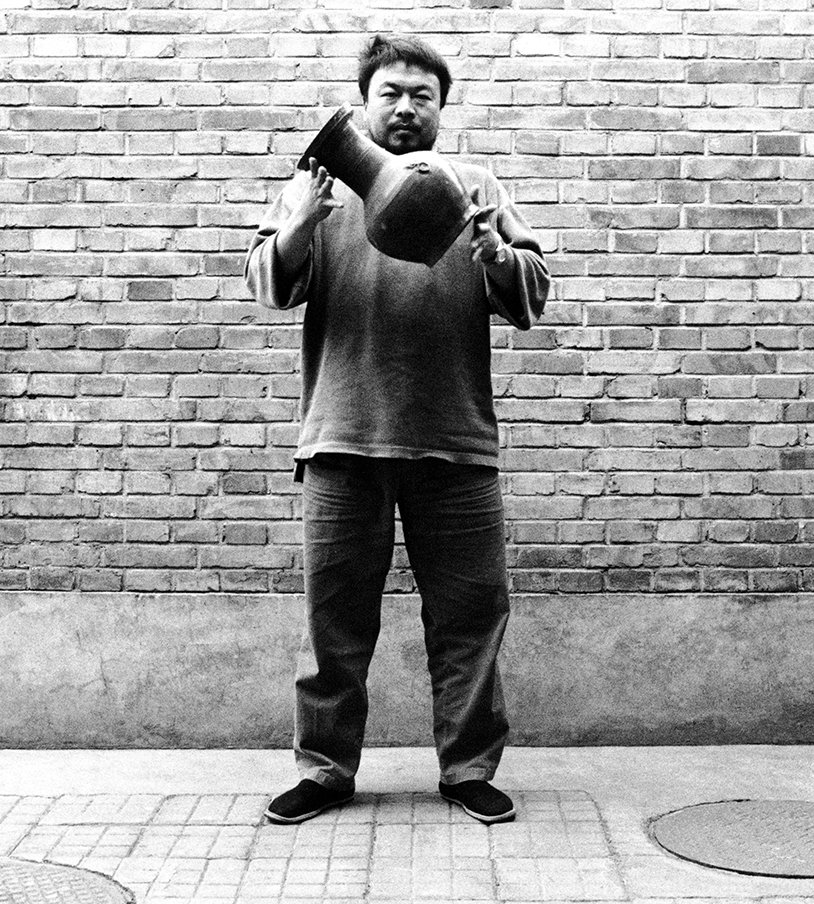

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

By Ai Weiwei (b. 1957), 1995

Photographic triptych

TWB Back to your more recent exhibitions: I’m interested in how you are able to incorporate and appropriate antiques, real ancient objects, and put them into contemporary contexts. For instance, in your most recent exhibitions in Beijing you put a giant Ming dynasty wooden structure, the Wang Family Ancestral Hall, into two galleries in Beijing’s 798, or at Chambers Fine Art you installed a collection of historical blue-and-white porcelain shards with tiger motifs.

AWW I think this so-called ‘contemporary art context’ is a battlefield of judgements. If anything works well, it will always raises questions about our values and history. So I think it is very interesting to insert those things into new contexts, to present a very direct challenge to what is the norm.

TWB How does that contrast with contemporary readymades? Are these ancient readymades?

AWW With any readymade you really have to ask yourself: ‘Is it ready?’ This so-called ‘readiness’—which is not just physical but also mental—that is, are our minds able to accept it in a certain way? For this to occur, it needs to be something that is already affiliated with our value judgements. Like when Duchamp used the urinal—of course it totally subverts the whole function and meaning of a urinal, but before that, it also has to have a certain recognizability as a common object, something that people already have a fixed judgement on. Only then can the power comes out.

TWB Do you think it is important for contemporary artists to have an appreciation of traditional art?

AWW At the beginning I was kind of hesitant [to delve into the past with my art], because if you see yourself as a contemporary artist, somehow this means a break from the past, right? But I gradually became interested in knowing: what is the ‘past?’ What are we trying to break away from? I think it is interesting to challenge very traditional aesthetics and established meanings behind objects, religion and conventions. In the simple act of making a table, stool or something you can clearly show both your modern conception and your understanding of the traditional.

TWB When you arrived in China in the mid-’90s you said that local people didn’t appreciate antiquities. Do you think China has a better appreciation of the traditional today?

AWW That depends. Today, you can see a nation that has completely lost its sense of traditional aesthetics and philosophy, so it tries to grab at anything it can. There is this idea of perpetuating so-called ‘Chineseness’, but that is an empty word. Tradition is always interpreted and misinterpreted, but new culture can be very brutal; interpretations can actually be very rough, and can destroy the intention.

TWB With regard to destruction, many people feel that part of being a collector is that you are also a custodian. How can you explain the work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995)?

AWW People always ask me: how could you drop it? I say it’s a kind of love. At least there is a kind of attention to that piece [because of the photograph]. There are hundreds of thousands of similar Han dynasty vases, and you can easily buy them. I still have a photo of when I was in Xi’an. There was a farmer sleeping on top of these two urns waiting for someone to pay him a few hundred yuan. For him that was a few month’s salary, but even then nobody wanted them. So [to me] the act is not like I destroyed a Rembrandt, it’s not like there is a limited number.

TWB Did you say to yourself: ‘I have two similar vases, I am going to break this one’?

AWW Not really. To tell you the truth, this work was not even made for art. I had just bought a Nikon F3 that could be programmed to take a series of frames one after another. These photographs were an experiment. I never planned the act, I just told my friend Rong Rong: ‘Let’s do this.’ In fact, the tragedy is that we first tried one, and I was sure we did not catch it. I think Rong Rong was too nervous. So I said: ‘Let’s do another one.’ Remember, it’s not like today, this was film—you could not see what you were getting. And then after that I just forgot about the photographs … they were never made as artwork.

TWB But I have seen the photographs you took in New York and some of the art you made back then …

AWW As you know, when I was in Beijing I was collecting and not making any art. I tried to do something in New York, but I realized that nobody wanted me to be part of the art society. I could not sell a piece. When I got home, I threw out more than half of my art. If you do something and no one else appreciates it, why do it? It still comes down to a value judgement: if you only have a small room and it is filled with canvases, they are the first thing to get tossed out because you need a place to sleep. So I did not use these photographs [of dropping the urn] until very late. I thought it was creepy to do things like that. But in the end it became a kind of iconic image for me. Stupid enough, I guess.

TWB But it’s powerful, there is power in the act …

AWW The power comes not from the act but from the audience’s attention, the challenge to their values. The act is easy—every day we can drop something, but it is when we are forced to come face to face with this action and make a judgement … that is the interesting part.

TWB Speaking of strong acts, what was your reaction when Maximo Caminero smashed one of your works in Miami?

AWW [Maximo] said that he was encouraged by me or something. I am not surprised, I am not upset, but to me his argument does not justify him doing that. You cannot just walk into a museum and destroy any work of art—it doesn’t belong to you, it’s a violation of the law. That is another judgement about violating other people’s rights.

TWB May I ask, what is your current state of affairs? You are on the cusp of getting your passport back, you just opened three very successful solo shows in Beijing: has China’s government changed their stance towards you?

AWW I think on both sides we are more relaxed. I cannot speak for the government, but I am much more relaxed. We are not born knowing how to handle everything, but certain things, certain ways of behaving do change and we grow. Of course certain beliefs never change: they are pre-programmed in our genes; fixed. It doesn’t matter, love or hate—it takes time, it takes energy, it takes experience.

Tiffany Wai-Ying Beres is an independent Beijing-based curator and art historian.

All images in this article are courtesy of and © Ai Weiwei.

This article first featured in our October 2015 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.