Sigiriya: An Early Designed Landscape in Sri Lanka

Inscribed today on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, Sigiriya, an archaeological site in central Sri Lanka, may be one of the oldest gardens known in Asia. The late antique (4th–7th century) remains of buildings, zoomorphic architecture and rock paintings upon its central outcrop have elicited interpretation since the late 19th century (Figs 1 and 2). Sigiriya was thought to be a palace complex, and the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy likened its paintings to the Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE) cave paintings at Ajanta in India (Coomaraswamy, 1971, p. 163).

Sigiriya was deemed a royal pleasure garden for the first time in the middle of the 20th century, when excavations at the base of the geological feature exposed a set of rectilinear water terraces with constructed rills, fountains, drains and underground channels (Fig. 3). At the tenth general assembly of the International Council on Monuments and Sites in 1993, Senake Bandaranayake, a prominent Sri Lankan conservation archaeologist, brought global attention to these constructed landscapes. Today, most archaeologists and historians consider Sigiriya’s water architecture evidence of a very early, if little known, garden culture in South Asia.

The scale, symmetry and construction design of Sigiriya’s visible landscape architecture astonish even today (Fig. 4). At the centre of the plan is an inselberg-type outcrop rising 180 metres above the surrounding terrain. Fifteen hectares of terracing with walls of stone and earth around its base ground the rock’s precarious vertical rise. Tropical vegetation, typical of Sri Lanka’s dry zone, obscures two walled rectangular areas east and west of the rock, referred to in the literature as ‘precincts’. Their brickwork dates to the first millennium CE. A longer rectangle (1 x 3 km) bounds the plan and composes the extent of the archaeological site. Framed by unexcavated earthen mounds and discontinuous moats that are visible from the air, the site’s scale and rectangular shape attest significant landscape planning. However, only one third of the site has been carefully surveyed, even less has been excavated, and just a fraction has been phased over time in the published scholarship. Although there are over one hundred test excavations across the site, the full extent of Sigiriya’s constructed landscape remains unknown. Compared to better-known historical gardens in South Asia, such as the funerary gardens of the Taj Mahal, Sigiriya’s status as a garden is not, at this point, indisputable.

Fig. 1 Building remains on the summit of Sigiriya rock as seen from the south

Fig. 2 Paintings conserved in a niche on the western face of Sigiriya rock

The formal layout of an interconnected set of three water features reflects a highly refined landscape design sense on the part of Sigiriya’s architects (Fig. 5). Preserved in the western precinct on either side of a bisecting east-west path, their underground infrastructure indicates significant hydrologic control, seemingly for pleasure.

First, two large concentric squares intersected by perpendicular causeways define a central island. The trenches contain traces of a water-resistant plastering. Water conduits placed at varying depths could suggest that water was controlled at different levels across the four quadrants. Flights of steps descending into the trenches indicate that they may have been used as bathing pools.

Often compared with the chahar-bagh form known from Mughal gardens, this quadripartite ‘water garden’ is immense—about 115 metres on a side—and only visible from above. Two rectangular extensions further complicate the form. Moreover, excavations southwest of this four-part feature have revealed what Bandaranayake described as a ‘miniature water garden’ (Bandaranayake, 1999, p. 18; 2013, p. 26); a LiDAR scan might reveal the extent to which similar structures for water surround the central squares.

Second in succession from west to east, the ‘fountain garden’ is narrow: a set of long, linear open pools fed by serpentine streams. Here, water was on display, bubbling up through perforated limestone plates set into the paving. The fountains operated when gravitational pressure forced water (conducted via underground pipes) up through the holes. On both sides of this fountain garden, four mounds laid out symmetrically, north to south, were in fact moated islands. Seasonal pavilions from which to view the fountains may have been built onto brick foundations at their rocky highpoints.

Fig. 3 The excavated ‘water gardens’ in the western precinct

(After Google Earth imagery, 7/22/2009, Digital Globe)

The loose boundaries of the third water garden begin a few steps east of the fountain garden and end at large retaining walls supporting the terraces around the central outcrop, known generally as ‘Sigiriya rock’. A blocky platform edged with L-shaped water trenches integrates certain irregular features into its plan, most notably a small octagonal terrace, which relates to an irregular octagonal pool built around a large boulder just north of the platform.

After a new drive was built between 1960 and 1963, diverting Inamaluva-Sigiriya Road at the Ramakele stupa toward the old Western Gate, visitors could begin to experience Sigiriya along its ancient east-west path rather than from the former main entrance just south of Sigiriya rock. By the 1980s, conservation archaeologists presented this east-west path as the main path through the site and therefore constructed contemporary viewsheds of the site along it. Visual access to ongoing site conservation from what has become Sigiriya’s iconic major bisecting longitudinal axis contributed to interpretations of the site. The overall bilateral symmetry of the archaeological landscape was thus emphasized, and new views through the ‘pleasure gardens viewing the ponds’ (ASCAR, 1959, p. G38) were curated.

These views can be enjoyed from several points along the main path and even while climbing the great flights of limestone-inlaid steps through the rocky boulders around the base of Sigiriya rock. For example, while visiting the famous rock paintings noted by Coomaraswamy (which I will not have a chance to discuss here; see Fig. 2), one obtains a view of the fountain garden from high above the tree canopy. From this vantage point, we can understand the water features’ square and rectangular forms. Their scale and architectonics must have seemed similarly impressive in the past. Such views have become central to contemporary site experience, alongside the rock paintings and building remains. These unanalysed experiences of landscape, I argue, provide interpreters with an important window onto Sigiriya’s past as a ‘garden’. When he described Sigiriya as a garden for the first time, Senarat Paranavitana, Sri Lanka’s archaeological commissioner from 1940 to 1956, said, ‘The entire plan of the garden is unfolded when one stands on the summit of the rock’ (ASCAR, 1952, p. G18). Physical bounding of the site plan, an important consideration for archaeological gardens and fields (Gleason, 1994), can be seen from the summit. Oddly, no one mentions a view I find especially striking: from along the east-west path gazing toward the looming rock itself, a curiously prominent reddish horizontal stripe (indicating the Mirror Wall; see below) marks every photograph of Sigiriya’s western rock face (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4 Sigiriya site plan drawn to scale showing the central outcrop, surrounding terraces, two inner precincts, moats and bounding wall of the outer precinct

(Drawing by the author)

Sri Lanka’s well-developed garden culture is documented in the early Pali chronicles and compares with descriptions of garden use in the Sanskrit literature of early India. Royal parks and woods were offered to Buddhist ascetics, whose practices and interactions with the lay community eventually transformed informal wooded retreats into formal monastic spaces. Monastic parks are among a set of attested designed landscapes, which also included hunting parks, royal pleasure gardens, orchards and managed woodlands. As mentioned, Sigiriya’s water gardens have been considered by scholars to constitute a royal pleasure garden (Ali, 2003; Bopearachchi, 2006; Cooray, 2012). Other archaeological examples of the type in Sri Lanka include Ranmasu Uyana in Anuradhapura, the provincial royal complex at Galabadda and the pleasure gardens of Dip Uyana in Polonnaruva; stone remains at these sites date roughly from the 7th, 11th and 12th centuries, respectively. Despite vast differences in scale (Sigiriya being larger), Sigiriya’s brick water structures form a typological group with these medieval pleasure gardens.

We have limited evidence, but a long tradition attributes Sigiriya’s site construction to King Kassapa (r. 477–95). In the Culavamsa, a Pali chronicle compiled iteratively about the Sri Lankan kings, a Buddhist monk called Dhammakitti redacted in the 13th century a royal event concerning Sigiriya. He claims that King Kassapa ‘cleared (the land) about, surrounded it with a wall and built a staircase in the form of a lion. Thence it took its name (of Sihagiri) … Then he built there a fine palace, worthy to behold, like another Alakamanda and dwelt there like (the god) Kuvera ...’ (Geiger, 1928, 39:3–6, pp. 42–43). This tradition of linking the site architecture to a king was documented well before Dhammakitti’s time by visitors to Sigiriya whose writings can be dated palaeographically. For example, an anonymous visitor writing on the Mirror Wall (which is covered with inscriptions; see below) in the late 8th or early 9th century prefaces his poem with his expectation of a palace: ‘Having heard according to (one’s) desire and knowing that the mansion of the king attracts (one’s) mind …’ (Paranavitana, 1956, verse 156, pp. 95–96). We know very little else about the landscape architectural programme of Kassapa, considered to be Sigiriya’s patron-king.

When we come across a geographical feature as unique, powerful and visually arresting as Sigiriya rock, we should expect a rich landscape palimpsest. Its distinctive chimney shape can be recognized for kilometres (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the region is a ‘continental divide’ of sorts, with rainwater runoff parting to either flow northeast toward the Bay of Bengal or northwest to the Arabian Sea via the Gulf of Mannar. Locating a more sacred ecological landscape in Sri Lanka’s northern peneplain would be difficult.

Fig. 5 Sigiriya pleasure garden architecture showing water garden with chahar-bagh form; fountain garden with perforated limestone plate; and water terrace with octagonal terrace and related octagonal pool

Fig. 6 View of Sigiriya rock with Mirror Wall from the main path

(Photograph: krivinis/Shutterstock.com)

Fig. 7 Distant view of Sigiriya rock and its Mirror Wall from 11 kilometres southwest, taken from the grounds of Heritance Kandalama, a hotel designed by Geoffrey Bawa

Archaeology offers an ancient origin story. An early inscription on the boulder adjacent to the octagonal pool describes the donation of monastic dwellings and audience halls. Surrounding Sigiriya rock, at least thirty scattered boulders contain prehistoric rock shelters first converted for use by ascetics and later serving as monastic habitation (Figs 8 and 9). At the turn of the first millennium, the lay patrons of an ascetic or of his particular Buddhist sangha sponsored embellishments to these dwellings as meritorious acts. These included drip ledges cut for protection against monsoon rains and interior paintings. Painting traces within these caves could tell us via pigment analysis the duration of their use. The caves are connected via paths, steps and landings, and built up with ancient bricks; pedestrian movement between and among caves was organized around focal points like stone seats, pavilions and water features. C. E. Godakumbura, archaeological commissioner of Sri Lanka from 1961 to 1967, and Senake Bandaranayake have both reported evidence for alterations and additions made to Sigiriya’s built environment during its post-Kassapan ‘monastic phase’ (ASCAR, 1961, p. G37; Bandaranayake, 2013, p. 28). Some scholars even read a reference in the Culavamsa as evidence for King Kassapa’s posthumous donation of these grounds to a group of Dhammaruci monks (a heterodox sect associated with Abhayagiri Monastery, which broke off from the main Theravada tradition) (De Silva, 2002, p. 10). Yet, architectural histories of Buddhist monasteries in Sri Lanka do not cite or spatially analyse Sigiriya’s so-called boulder garden.

Crediting King Kassapa with the site’s water architecture, in fact, requires a suspension of disbelief. Neither inscriptions nor scientific dates support the case. Only by observing how the built architecture lies on the land might we believe we are in King Kassapa’s Alakamanda (the metaphorical palace and garden complex of gods), as suggested by Paranavitana (Paranavitana, 1950). The plan of the western precinct clearly relates to views from the summit of Sigiriya rock in multiple architectonic ways. One sees its iconic axis from the painting-viewing gallery, from the lowered wall at the end of the Mirror Wall corridor (Fig. 10) and from the summit of the rock behind the first set of ruins. No textual records are needed to admire building virtuosity here. Orthogonality, symmetry and scale are orchestrated masterfully and from multiple viewing prospects. Efforts to understand Sigiriya’s archaeological paths and present them to a contemporary cultural public transformed the primary object of the visit itself—from the remains of a palace on top of a rock to a stroll through its gardens below. But regardless of Sigiriya’s origin story, we have to accept several significant afterlives to understand its landscape design (Hunt, 2004). Monastic evidence should therefore contribute to its garden history.

When building interventions transform the lie of the land, we confront an art of milieu: that is, both a physical object with formal qualities and a place experienced by subjects (Hunt, 2000, pp. 8–9, 15; see also Berque, 1990). Gardens are especially refined acts of place-making that transform the experienced landscape via physical forms, some organic and changeable (like plants) and others inorganic and stable (like rocks). The design and construction feat of Sigiriya’s monumental water architecture indicates an early garden by this definition—that is, an art of milieu from a very early period.

Fig. 8 Boulder with drip ledge, plastered brick walls and paintings

Fig. 9 Boulders over limestone-inlaid steps

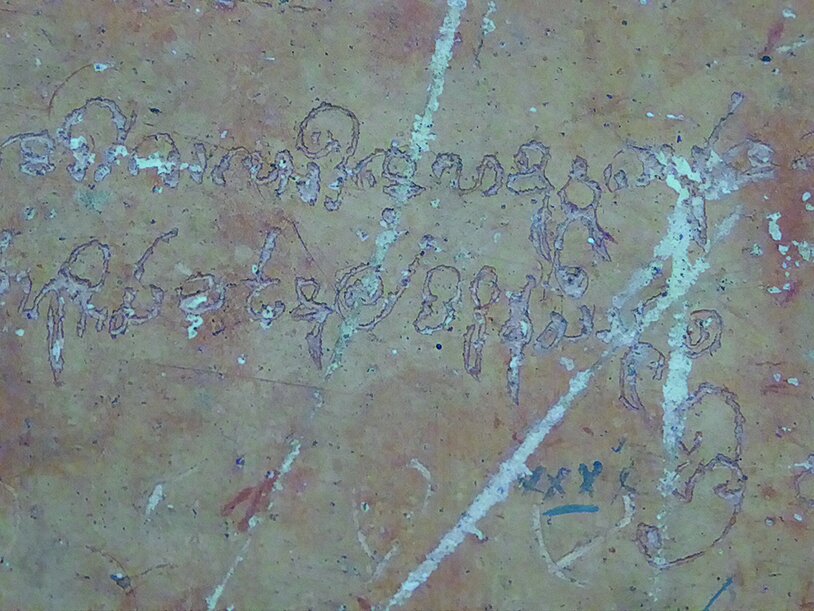

Here is the rub. Other architectonic relationships also strongly suggest an art of milieu at Sigiriya, for example the relationship of Sigiriya’s iconic axis to the Mirror Wall gallery. When a visitor finds herself inside the tight corridor between built wall and undulating natural rock surface, the Mirror Wall blocks all views—including what is arguably the best view along its central axis, over Sigiriya’s water gardens. Moreover, during one of Sigiriya’s afterlives, people visited by the thousands and recorded their experience of Sigiriya here on the Mirror Wall (Fig. 11). In fact, the Mirror Wall seems to have been designed for this practice. Tall enough to block the view, it forced the interiorization of experience; plastic enough to accommodate verbalizations of that response as etchings onto its special limestone plaster coating, the Mirror Wall thereby engendered an art of milieu at Sigiriya. During this culturally programmed act of ekphrasis, features at Sigiriya prompted visitors to participate in a new practice of poetic response at the Mirror Wall. Its position (along Sigiriya’s iconic axis) and programme (reflecting on the experience of Sigiriya) thus designed the landscape. In front of the Mirror Wall, the water gardens and other designed features became deictic—existing simultaneously as both themselves and the visitor’s mental perception of them.

More than 1,400 verses became part of Sigiriya’s landscape architecture between the 7th and 13th centuries in this way. The conceptualization and construction of such a Mirror Wall, as both a landscape architectural feature and a site for literary practice, produces the greatest evidence for masterful early landscape planning at Sigiriya (Kumar-Dumas, forthcoming). At the Mirror Wall, visitors experienced place and a certain pleasure: ‘… (By you) has (also) been caused, at Sihigiri, the bristling of hair which thrills the whole body.’ Or, ‘As I came (here) bringing (with me) means of sustenance, delight came (into being) from the abundant splendour of this …’ (Paranavitana, 1956, verse 69, pp. 41–42 and verse 356, pp. 221–22). The practice both indexed and landmarked the Mirror Wall’s architectural position within its contemporaneous cultural landscape. After visiting the Mirror Wall, that striking view of it both from the main path and also from distant points in the greater landscape transformed a curious reddish band across Sigiriya rock into a marker of collected landscape experience at Sigiriya. Herein, perhaps, lies a deeper understanding of the early garden.

While hydrological feats impress, the Mirror Wall was the garden’s planning marvel. By materializing the long record of early visitor experiences into an architectural feature of the overall landscape plan, it conveys human experience of Sigiriya to immediate and future visitors, transforming, via story, new experiences of the place. The stories accommodate ancient monastic cave dwellings, rock paintings, monumental watercourses and fountains, and even the building remains resembling a vast palatial complex high upon a rock. Via the stories, all of these features submit to the idea of a garden whose design was directed by practices at the Mirror Wall. The designers of this practice and landscape, perhaps residents of the monastic community below, enabled visitors in the past to resuscitate even a derelict garden from its archaeological landscape. Until archaeologists employ contemporary methods to visualize more of the site, it is the Mirror Wall’s relationship to the overall site design that commands attention. The great landscape work had already been achieved at the Mirror Wall high on a rocky outcrop before the 7th century CE, whether designed by monks or kings. As such, Sigiriya remains among the earliest examples in Asia of landscape architectural mastery.

Gardens have an afterlife often as interesting as the speculative tale of origins surrounding them. The afterlife of the landscape at Sigiriya raises questions about what constituted its great design moment—and can restore to this archaeological garden its former life.

Fig. 10 Mirror Wall corridor looking north

Fig. 11 Verse fragment etched on the Mirror Wall by an early visitor

Divya Kumar-Dumas is a doctoral student of architectural historian Michael Meister in the Department of South Asia Studies, University of Pennsylvania. She also practises garden design in the Washington, DC area. Deeply influenced by studies of archaeological and designed landscapes, her work contributes to conversations about the relationship of cultural processes to terrain facts. She thanks the American Institute of Sri Lankan Studies for supporting her research.

Unless otherwise stated, all images are by the author.

Selected bibliography

Daud Ali, ‘Gardens in Early Indian Court Life’, Studies in History 19, no. 2 (2003): 221–52.

ASCAR (Archaeological Survey of Ceylon, Annual Reports).

Senake Bandaranayake, Sigiriya: City, Palace, Gardens, Monasteries, Paintings, Colombo, 2013.

—, Sigiriya: City, Palace and Royal Gardens, Colombo, 1999.

—, ‘Sigiriya: Research and Management at a Fifth-Century Garden Complex’, Journal of Garden History 17, no. 1 (1997): 78–85.

—, ‘Amongst Asia’s Earliest Surviving Gardens: The Royal and Monastic Gardens at Sigiriya and Anuradhapura’, in International Council on Monuments and Sites, Tenth General Assembly, Historic Gardens and Sites, 1993, pp. 1–36.

Augustin Berque, Médiance, de milieux en paysages, Montpellier, 1990.

Osmund Bopearachchi, The Pleasure Gardens of Sigiriya: A New Approach, Colombo, 2006.

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, History of Indian and Indonesian Art, New Delhi, reprint, 1971 (1927).

Nilan Cooray, ‘The Sigiriya Royal Gardens: Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic Composition’, Architecture and the Built Environment, no. 6 (2012).

Raja De Silva, Sigiriya and Its Significance: A Mahayana-Theravada Buddhist Monastery, Colombo, 2002.

Wilhelm Geiger, trans., Culavamsa Being the More Recent Part of the Mahavamsa, Part 1, 1928 (English trans. from the German, Mabel Rickmers, Colombo, 1953).

Kathryn L. Gleason, ‘To Bound and to Cultivate: An Introduction to the Archaeology of Gardens and Fields’, in Naomi F. Miller and Kathryn L. Gleason, eds, The Archaeology of Garden and Field, Philadelphia, 1994, pp. 1–24.

John Dixon Hunt, The Afterlife of Gardens, Philadelphia, 2004.

—, Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory, Philadelphia, 2000.

Divya Kumar-Dumas, ‘Reading Architecture in Landscape: Sigiriya Reflections’, in Lucas den Boer and Elizabeth Cecil, eds, Confrontations in Context: Intellectual and Lived Spaces Across South Asia and Beyond, Berlin and Boston, forthcoming (2018).

Senarat Paranavitana, Sigiri Graffit Being Sinhalese Verses of the Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Centuries, vol. 2, London, New York, Bombay and Madras, 1956.

—, ‘Sigiri, the Abode of a God-king’, Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Centenary Volume, 1845–1945 (1950): 129–83.

Tom Turner, ‘Buddhist Gardens’, in Asian Gardens: History, Beliefs and Design, London and New York, 2011, pp. 138–70.

This article first featured in our January/ February 2018 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.