The Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena, California

For over a century, the elegant, meditative qualities of Japan’s gardens have been greatly admired in the West. In the late 1800s, small Japanese gardens—along with teahouses and pavilions—were built at international expositions throughout Europe and the Americas as part of Japan’s efforts to promote the ancient, spiritual and tranquil aspects of its culture as the nation busily industrialized. Soon thereafter, the Japanese government began funding the construction of ‘friendship gardens’ in the West to promote strong cultural and commercial relations between Japan and other nations. As a result of these efforts and the Japonisme vogue that swept much of the West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many wealthy Europeans and Americans not only collected Japanese art, but also commissioned landscape designers to recreate Japanese-style strolling gardens, tea gardens and later, rock-and-gravel dry gardens on their private estates.

Numerous Japanese gardens of all types were created throughout the 20th century on the West Coast of the United States in particular, because of the region’s geographical proximity to Japan and its substantial Japanese immigrant population. It was largely these immigrants who designed, built and managed many of the private gardens commissioned on the West Coast, often modelled on famous gardens in Japan but incorporating local vegetation and landscape features. The Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena, California, originally built in the 1930s by one Japanese immigrant designer and restored 70 years later by another, is both a masterwork of Japanese-style garden design in the US and testimony to the resilience of a community that has not always received the same level of admiration as its gardens (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Niko-an (‘Two-pond Retreat’) Teahouse and pond

Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden

(Photograph: Deanie Nyman)

(Image courtesy of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, Pasadena, CA)

The Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden was commissioned by Charles and Ellamae Storrier Stearns, an elegant couple who met in middle age after several previous marriages each (Fig. 2). The couple lived a glamorous life travelling between the US (Pasadena and the East Coast) and France, where they kept homes in Paris and Nice, and both had travelled to Asia. Like many wealthy Americans and Europeans of this era, the Storrier Stearnses deeply admired things ‘Oriental’, and in particular, Japanese. Ellamae yearned for a Japanese garden and teahouse on their estate, which stretched over seven city lots in Pasadena and featured a three-storey Georgian mansion. In 1935, the Storrier Stearnses therefore commissioned a young landscape designer, Fujii Kinzuchi (1875–1957), to convert their tennis courts into a tranquil Japanese garden for their enjoyment (Fig. 3).

Unlike traditional European and Middle Eastern gardens, which are often characterized by highly structured arrangements of flowers, trees and other plants and by a profusion of colour, Japanese gardens are generally designed to mimic nature and to encourage calmness and contemplation. They typically feature irregular, asymmetrical placements of rocks and plants and a subdued palette, with an occasional bloom amidst the greenery rather than richly coloured beds. Over the course of five years, Fujii transformed the almost two-acre, flat space into a place of understated natural beauty. Digging out two ponds at the heart of the garden and using the earth to build up hills on the eastern side, he gradually created a kaiyu-shiki-teien, a type of garden that first appeared in the Edo period (1615–1868) on the estates of Japan’s nobles or military lords. Typically translated as ‘strolling gardens’ or ‘promenade gardens’, these gardens were built to complement the sukiya-style (lit., ‘elegant abode’) villas of the elite, structures that were modelled on the austere but exquisitely constructed teahouses that signalled cultural sophistication from the 16th century on.

Fig. 2 George and Ellamae Storrier Stearns in their Japanese garden, c. 1940

(Image courtesy of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, Pasadena, CA)

Fig. 3 Fujii Kinzuchi at work constructing the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, c. 1939

(Image courtesy of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, Pasadena, CA)

These strolling gardens were designed artfully to encourage visitors to follow a path clockwise around a central body of water, from one carefully composed scene to another. Designers employed two techniques to compose these scenes: shakei, or ‘borrowed scenery’, which incorporated mountains or forests beyond the garden into the view, making the garden appear larger; and miegakure, or ‘hide-and-reveal’, which used winding paths, fences, bamboo and buildings to hide views until visitors arrived at the best viewpoint. Ideally, visitors would walk through the space in a relaxed but mindful state, enjoying the scenery and allowing the tranquillity to seep into their bodies and minds.

Fujii was well aware of this traditional Japanese ideal as he shaped his strolling garden for the Storrier Stearnses, adding many of the features found in traditional Japanese gardens—ponds with bridges and stepping stones, waterfalls, stone lanterns and a small covered bench for sitting, slowing down and enjoying the view (Fig. 4). According to the garden’s records, he stated, ‘I am possessed of an ambition to leave a real, uncompromising Japanese garden in the United States’ (<www.japanesegardenpasadena.com>), one that was more true to Japanese aesthetic and spiritual principles than any other he had designed. However, he understood that the inner spirit of the garden was even more important than its outer form, and worked with the plants and materials available to him in Southern California to create a space that, as well as being essentially Japanese, feels rhythmic and natural.

Integrating native plants into Japanese-style gardens was very much in keeping with trends in Japanese-style garden design in North America from the 1890s, when Japanese gardens were first built on the West Coast, and, according to Kendall Brown, these gardens are ‘distinctly North American rather than imitations of “authentic” Japanese gardens’ (Brown, 1999, inside front cover). Many of the trees Fujii planted were also local, like redwoods and sycamores, or from other parts of the US, like the large magnolia that now lords it over the garden. He and his construction team used mules to carry large boulders from the Santa Susana Mountains northwest of Los Angeles, placing them at strategic points to create the waterfalls, stepping stones and foundation stones of the teahouse. The twelve-mat teahouse itself was the gem of the garden, designed by Fujii and built in Japan. It was then disassembled, shipped to the US and rebuilt on a foundation of three large boulders.

Fig. 4 Japanese stone lantern and redwood tree

Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden

(Photograph: Meher McArthur)

After five years, around 1940, the garden was completed, to the delight of Fujii’s patrons. Sadly for Fujii, however, the love of Japanese culture, art and gardens in the West did not always extend to a love of Japanese people. For the first decades of the 20th century, the US government treated Japanese immigrants as second-class citizens, and in 1942, when war broke out between Japan and America, Fujii was sent to an internment camp with over 100,000 other Japanese Americans. They were allowed to pack just one suitcase, and when Fujii left for the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona, in his case were the plans for the teahouse of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden—a key element of what he considered to be his life’s greatest work. A few years later, the future of his masterwork also came into question. Charles and Ellamae Storrier Stearns had no children, and in 1950, after they had both passed away, their Pasadena estate was auctioned off.

The estate was purchased on a whim by Gamelia Haddad Poulsen (1903–85) (Fig. 5). A Pasadena-based art dealer of Syrian heritage, Poulsen had originally attended the sale to buy two Louis XV chairs. However, when she realized that no one was bidding on the property as a whole, she bought the entire estate. Over the next few years, she sold the mansion and most of the land, keeping only the Japanese garden and building her family home in it. She was able to enjoy the garden for the next 25 years, but in 1975, plans made by the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) to build a freeway extension through Pasadena posed a threat to its survival. CalTrans used eminent domain (the right of a government or its agent to expropriate private property for public use, with payment of compensation) to take over almost half of the garden, and in 1981 a fire destroyed the teahouse. Believing the garden lost, Poulsen let it fall into ruin.

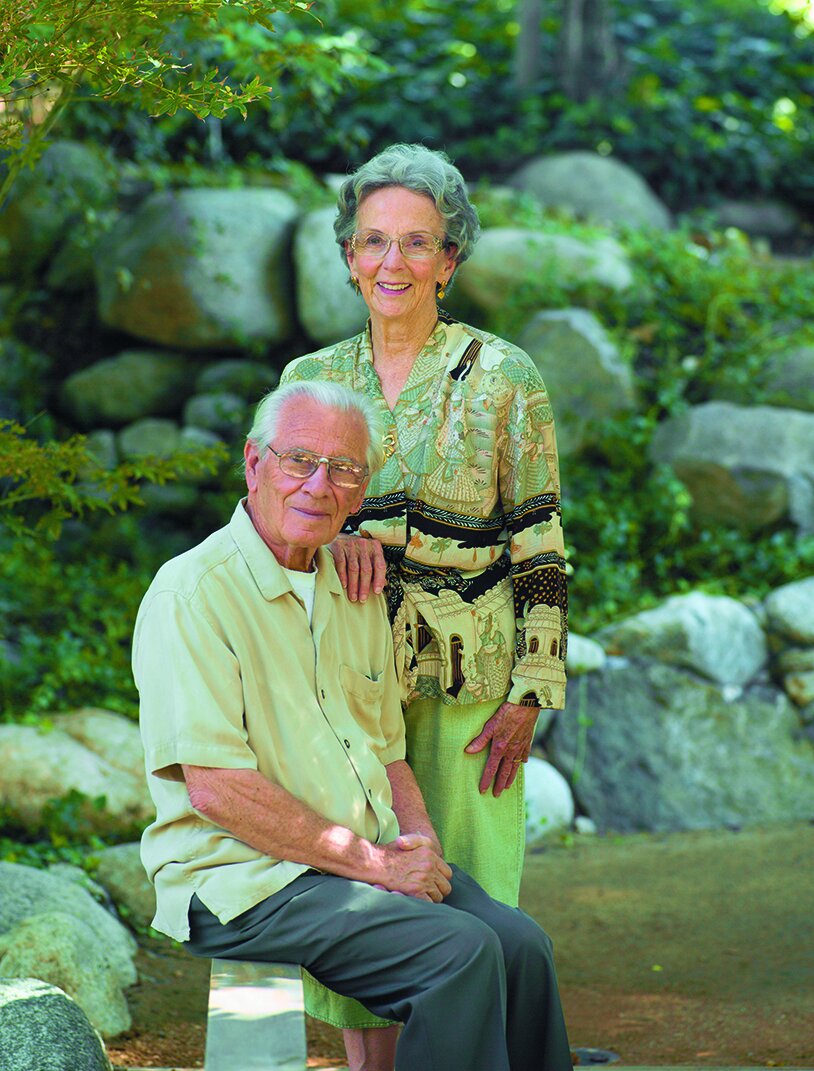

When Poulsen died in 1985, her son Jim Haddad and his wife Connie (Fig. 6) inherited the house and garden, which was in a state of disrepair. Initially they were unsure what to do with the property, but in the mid-1990s, when it became clear that the freeway extension was no longer going to run through the Japanese garden but would instead be built as a tunnel beneath the neighbourhood, they decided to restore and preserve it for others to enjoy. Over the next decade, with the permission of CalTrans, who still owns a part of the garden, they invested considerable time, energy and funds in returning the garden to its original state, once again with the assistance of Japanese Americans. They reconnected with Fujii’s family in California, who still had the plans for the teahouse that Fujii had kept safe in the internment camp. The plans helped them give a second life to the garden and rebuild the teahouse, though this time on a sturdier foundation.

Fig. 5 Gamelia Haddad Poulsen, c. 1935

(Image courtesy of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, Pasadena, CA)

Fig. 6 Jim and Connie Haddad, c. 2015

(Photograph: Deanie Nyman)

(Image courtesy of the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden, Pasadena, CA)

In addition, a prominent Southern California garden designer, Takeo Uesugi (1940–2016), who was responsible for designing some of California’s finest Japanese gardens, offered his services over several years to masterfully restore the ponds (Fig. 7), hills, trees, paths and bridges to their original state, with a few upgrades, including wider bridges to allow for wheelchair access. As Fujii had before him, Uesugi incorporated indigenous plants into the garden landscape, and also introduced a number of drought-tolerant species to accompany the Australian tea tree and moss-like Korean grass used by Fujii (Fig. 8).

Today the garden is managed by Jesus Rodriguez, who is originally from Colombia but lived for many years in Japan, where he studied biotechnology and its applications in agriculture. By recycling all the refuse from the house and garden into nourishing compost and storing all the rainwater on the site and grey water from the house, Rodriguez ensures that this lush Japanese garden is managed and maintained in an ecologically intelligent and responsible manner and is sustainable in the hot, dry Southern California climate.

The garden’s current owners, Jim and Connie Haddad, have opened the garden to the public several days each month as a cultural and educational organization and as a place of contemplation and spiritual wellness. Just like the strolling gardens of the military lords and noble families of Japan five centuries ago, the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena serves as a place to slow down, to immerse the self in nature and to pay attention to each and every view that the garden offers. The passion and dedication of many individuals over almost a century to preserve such a space in Southern California suggest that such Japanese-style gardens are not only important reminders of traditional horticultural and artistic expressions of Japanese spirituality, but also vital spaces in today’s fast-paced global culture, in which people often forget to occasionally stop and simply breathe.

Fig. 7 Koi fish in the small pond

Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden

(Photograph: Meher McArthur)

Fig. 8 Large pond and Korean grass bank

Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden

(Photograph: Meher McArthur)

Meher McArthur is an independent Asian art curator, author and educator specializing in Japanese art. She lives with her family in Los Angeles.

This article is the first in a continuing series on gardens.

Selected bibliography

Kendall H. Brown, Japanese-Style Gardens of the Pacific West Coast, New York, 1999.

This article first featured in our January/ February 2017 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.