Bridging the Distance: Forging Connections with Islamic Art at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

In the new installation ‘Across Asia: Arts of Asia and the Islamic World’ at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, multimodal interpretation—from digital and analogue interactive elements to polyvocal didactics—serves to forge connections between the historical art on view and the 21st century museum visitor. This approach to the galleries of arts of the Islamic world in particular was brought to the fore in discussions with the Islamic Art Advisory Committee (IAAC), which I organized as the Wieler-Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow in Islamic Art (2019–22) with the essential support of museum colleagues and Dr Melissa Forstrom (State University of New York, Purchase) serving as the contracted facilitator. At the first meeting of the IAAC in May 2021, Tirzah Khan, an Ahmadi Muslim artist, graphic designer, and 2021 graduate of the University of Maryland Baltimore County, starkly spotlighted the main issue at the core of the installation by asking how we intended to ‘bridge the distance’ between the historical art on view and real people’s—and specifically Baltimoreans’—lived experience.

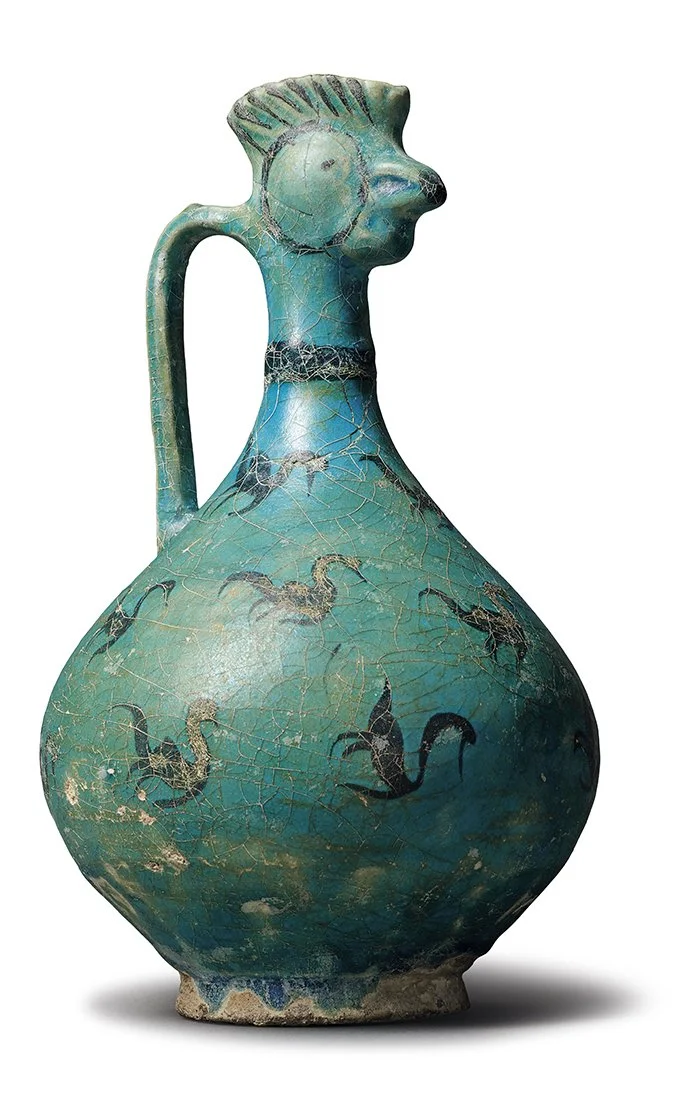

Fig. 1 Ewer with rooster-head spout

Iran; 13th century

Ceramic with glaze and underglaze; 25.3 x 14.6 cm

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1931

In collaboration with various teams at the Walters and external constituents, different gallery tools were developed to bridge said distance. One of these was designed with the museum’s Visitor Experience department and lets visitors select the aspects they would like to learn about ceramics from Iran dating from the 10th to the 17th century. Three thematic booklets aimed at families with children are located next to a large display case that is built to mimic historical cabinets of ceramics, known as chini-khana (‘china house’ in Persian), housing fourteen items from the Walters’s extensive collection of Persian ceramics, including a newly conserved ewer with a rooster-head spout (Fig. 1). One of the booklets asks visitors to imagine attending an elaborate feast in 1600s Iran and what it would feel like to use the ceramics on view, evoking multiple senses including smell, touch, and taste. Analogously, in the adjacent gallery, ‘Arts of Ottoman Lands’, a label written by members of the museum’s College Student Advisory Group (CSGA), established in 2022, brings to life a 19th century enamelled bronze incense burner (Fig. 2). The students’ cultural and familial associations with the smell of incense make personal the pervasiveness of incense in the Islamic world. In Ottoman lands specifically, incense was burned for both sacred and everyday purposes and in public and private places, from mosques and churches to palaces and other domiciles.

Fig. 2 Incense burner

Turkey; 19th century

Bronze with enamel; 17.3 x 21.3 cm

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1931

Despite employing the mediation of screens, digital interactive elements can also serve to bridge the distance between the art in the museum and the lived experiences of our community members. One such feature can be found in the gallery titled ‘Islamic Art Connections’. Here, examples from the Walters’s renowned collection of rare books and manuscripts are changed periodically, to prevent damage from long-term exposure to light. The inaugural installation in April 2023 includes an exceptional accordion album of calligraphy by the influential Ottoman calligrapher, Şeyh Hamdullah (1436–1520) (Fig. 3). Next to the cases with manuscripts, a video featuring the world-famous local artist, Mohamed Zakariya (b. 1942), explains the lifelong dedication needed to learn the art of calligraphy. From this video, visitors can hear a practicing calligrapher talk about the art form and see footage of the writing process—bringing forth sensory details, from the squeak of the pen’s nib on the burnished paper to the dark flow of the ink—and thereby gain a better understanding of how the historical manuscripts on view were made, centuries ago. Moreover, in conjunction with the Şeyh Hamdullah album, one of Zakariya’s own pieces of calligraphy recently acquired by the museum, Entreaty (2017), will be displayed, forging another connection between past and present. This juxtaposition is not merely an apt comparison of Arabic-language calligraphy but also a physical demonstration of the silsila (artistic lineage; literally, ‘chain’) of knowledge passed down from a master calligrapher to a student—a chain that remains unbroken from Şeyh Hamdullah, who lived in the Ottoman empire, to Mohamed Zakariya, who works and teaches in his studio in Arlington, Virginia.

The inclusion of another contemporary artist’s voice makes a connection to the past via the material of metal. Paul Daniel, a Maryland-based sculptor known for his kinetic sculptures, shares his perspective and insight on a label for a 17th century standard (‘alam) from Iran, created by Muhammad Taqi Ordubadi (act. c. 1660s) (Fig. 4). While the works of the two artists operate in different cultural spheres and appear vastly different at first glance, the parallels go beyond the materials and techniques of metalworking. As a processional standard, the ‘alam was once paraded through the streets of Iran on Ashura, the day commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Husayn at the battle of Karbala in 680. Despite the differences between the works of Paul Daniel and Muhammad Taqi Ordubadi, both make the most of metal and movement in public spheres.

Fig. 3 Album (muraqqa') of calligraphy

By Şeyh Hamdullah (1436–1520)

Turkey; calligraphy from the 16th century, bound in the 18th century

Opaque watercolour and ink on paper mounted on thin pasteboard, bound between sheepskin-covered boards with cold and chamois leather; each folio: 30 x 23 cm

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Acquired by Henry Walters, before 1931

By including different perspectives in the galleries, we also have been able to let the stories and voices of often marginalized communities be heard. For example, in the ‘Arts of Ottoman Lands’ gallery, including Armenian representation was vital not only to acknowledge their contributions to Ottoman art and architecture but also, in a very small way, to redress their frequent erasure, particularly in light of the genocide committed against them in the late Ottoman empire. Dr Khatchig Mouradian, an Armenian Studies scholar based at the Library of Congress, contributed a label for the jewelled gun of Mahmud I (illustrated in Adriana Proser's article ‘New Galleries at the Walters Art Museum: “Across Asia: Arts of Asia and the Islamic World”’ in this issue), in which he addresses these complex issues and underscores the importance of acknowledging Armenian artistic achievements.

Another group rarely represented in museum installations of arts from the Islamic world are sub-Saharan African and African-diasporic Muslims, including those once enslaved in the United States. Three didactic panels that relate to themes and objects in the installation—one in each of the galleries composing the ‘Arts of the Islamic World’—highlight stories and lived experiences of Black Muslims in America. This was a critical aspect of bridging the distance called for by Ms Khan, due to the fact that the Walters is located in Baltimore, a Black-majority city. For example, the story of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo is juxtaposed with the Walters’s 19th century West African loose-leaf Qur’an in a leather pouch (Fig. 5). Not only was Diallo enslaved in Maryland before gaining back his freedom and returning to his native Africa, thereby drawing a direct connection to the Walters’s history and location, but also a painted portrait of Diallo by William Hoare (c. 1707–92) shows him wearing around his neck a Qur’an in a leather pouch much like the one on display in ‘Across Asia’.

Fig. 4 Standard (‘alam)

By Muhammad Taqi Ordubadi (act. c. 1660s), Iran; 1664–65

Cast, hammered, and pierced iron; 125.5 x 42.2 x 1 cm

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Museum Purchase 2017

Furthermore, with a museum context calling attention to a bodily interaction with an object, visitors can use their imaginations to see life within the objects and appreciate how they once touched the lives of real people. In a few places throughout the gallery, this element of touch, and the power it can channel, is explored through the Islamic concept of baraka, or blessing. While objects of various media can be imbued with baraka, in ‘Across Asia’ a display case featuring a number of ornately decorated silver wearable objects from late 19th and early 20th century Yemen features several examples. A silver necklace with coral beads would likely have been a gift for an expectant mother, as the red colour and the coral material were thought to protect her during labour (Fig. 6). As a necklace, the power and baraka would be transferred to her through bodily touch and, like a wearable Qur’an, would specifically touch her heart.

‘Across Asia’ forwards the mission of the Walters Art Museum ‘to bring art and people together for enjoyment, discovery, and learning’ in various ways. The interpretive methods discussed in this article demonstrate the humans and the humanity behind the art on view in ‘Across Asia’. In particular, the galleries of arts of the Islamic world aim to bridge spatial and temporal distances, from the heart of Islam in Mecca to downtown Baltimore.