Village Abstraction: Patchwork Textiles in Rural China

Walking into a dusty, cluttered compound of three abutting households, a visitor cannot help but be drawn to a pink, red, blue, and grey patterned textile hanging over one doorway (fig. 1). Several windows also display uniquely designed patchwork covers. For what could easily be deemed a drab façade of arched entranceways, the householders have created dynamic and distinctive textiles in an array of abstract, geometric compositions.

But if a visitor makes any inquiries about patchwork textiles, in most villages the women shake their heads ‘no’. They answer: ‘We threw them out’; ‘I burned them all’. Thus arises the urgency to research, understand, and capture the explosion of creativity that for many years resulted in a rich artistic panoply of textiles made by women in rural China.

The historical trail of these Chinese patchworked textiles winds back almost two thousand years, with the entrance of Buddhism to China, and back at least another five hundred years in India. The tradition carried with it not only the concept of stitching together fabric scraps but also layers of meanings attached to such assembling. A direct though somewhat curvaceous line can be traced back from the doors and windows of northern Chinese villages to the teachings of the Shakyamuni Buddha in northeastern India. Before exploring the grand variety of patchwork creations by 20th and 21st century artists in the villages of Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Hebei provinces, it is valuable and illuminating to follow the path that led to this current and quickly disappearing art form.

1

House façade, Lüliang county, Shanxi province, March 2019

Photo courtesy of Lois Conner

2

Typical kashaya pattern as proscribed in Buddhist texts

Based on design in Yuan Zhao, Fozhi Biqiu Liuwu Tu (1080)

The teachings of the Gautama Buddha, born in Lumbini, in what is today Nepal, in the 6th or 5th century BCE, articulated a path to enlightenment available to all beings. He preached that, while his disciples were cultivating themselves, they should don a set of robes, which came to be called kashaya. The outermost of those robes, he detailed, should be constructed of rags, including those ‘chewed by cows, chewed by rodents, burnt, used for menstruation, used in childbirth, carried away from a shrine by birds, animals or the wind, taken from the graveyard, used to wrap corpses’, as was recorded in the Vinaya texts. In conversation with Ananda, his devoted attendant and disciple, the Buddha further instructed that these rags should be stitched together in a configuration of rectangles arranged to resemble the pattern of rice paddies. The decreed pattern consisted of cloth strips (from 5 to 25, depending on the importance of the individual and the ritual), each strip constructed of a line of rectangular cloth pieces, surrounded by a frame, with a square in each corner. The rectangles in each adjacent strip are offset, creating a pattern like a ‘running bond’ in brick walls (fig. 2). The sullied rags represented the monks’ rejection of luxury, and, as the Shakyamuni Buddha explained, the rice paddies symbolized the ability for all individuals to cultivate themselves and grow.

The root of the word kashaya in Sanskrit means brown, which would have been the colour of the rags that the Buddha had deemed appropriate for monks’ robes. Though some specified attributes of the kashaya, such as the colour, varied over time and across cultures, many Buddhist monks in China, Japan, and Korea still wear robes patched in the exact grid pattern laid out 2,500 years ago.

3

Subjugation of Nalagiri

India, Uttar Pradesh, Mathura; 2nd century CE

Sandstone; dimensions unknown

Indian Museum, Kolkata

(After Wikimedia Commons, https://w.wiki/8yER, accessed 26 January 2024)

4

Sculpture of monk wearing patchworked kashaya

China, Gansu province, Dunhuang, Mogao cave 285; Western Wei dynasty (535–56), 6th century CE

Painted clay; dimensions unknown

Photo: Lois Conner; © 1995 J. Paul Getty Trust

(After Whitfield et al., 2000)

Sculpted images of the Buddha and his disciples became more common in the 2nd century CE in India, and with them came visual manifestations of the kashaya. Prior to the 1st century CE, the Buddha was visually represented by nonfigural imagery such as his footprints, an empty throne, a dharma wheel, or a bodhi tree. By the latter half of the Kushan period (2nd century BCE–3rd century CE), artisans were creating sculptural depictions of the Buddha. In some extant stone sculptures, the patchwork robes can be recognized by engraved grid lines in the stone. The patchwork of these robes follows the precise grid patterns prescribed by the Buddha. One instance is on a sculpture from the Mathura region displaying the Buddha dressed in a patchworked kashaya. The detail is within a group of decorated railing pillars (now in the Indian Museum in Kolkata) that once surrounded the Bhutesvara stupa. On the front of the pillars are images of yakshis, while on the back are illustrations from the life of the Buddha. One scene depicts the story of the evil king Ajatasattu setting a wildly drunk elephant, Nalagiri, upon the Buddha, who ultimately subdues the raging animal (fig. 3). The Buddha wears a robe created from distinct vertical strips of cloth rectangles.

As Buddhism spread from India through what is today Pakistan and Afghanistan and into China, the concept of the kashaya travelled with it. In China, the word kashaya was transliterated to jiasha. By the Tang dynasty (618–907), other terms emerged, including shuitianyi (‘rice-paddy clothing’) and bainayi (‘hundred-patches clothing’). Murals in the Mogao Buddhist temple caves in Dunhuang present a plurality of visual evidence that the patchwork robes played a role in Chinese Buddhism. One of the earliest images of a jiasha in China is a multicoloured patchwork mantle wrapped around an early 6th century, painted clay sculpture of an almost life-size seated monk within a niche on the west wall of Cave 285 (fig. 4). According to an inscription on the wall, the cave was created between 538 and 539 CE, during the Western Wei dynasty (535–56). The red, brown, and blue-and-green rectangles of the mantle are laid out in the orderly stripped pattern first described a millennium earlier by the Gautama Buddha. This meditating monk is only one of many examples among the sculptures and murals from many different time periods at Dunhuang depicting buddhas, bodhisattvas, and monks wearing multicoloured jiasha.

5

Patchwork textile

China, Gansu province, Dunhuang, Mogao caves; Tang dynasty (618–907), 8th–9th century

Silk; 108 x 147 cm

Photo courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum

6

Kashaya

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), late 18th–19th century

Silk embroidery, satin, and damask; 114.3 x 209.6 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Patricia Pei, 2021

Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Dunhuang site additionally preserved several examples of actual patchworked jiasha. Acquired in Dunhuang by Sir Marc Aurel Stein, during his journey there from 1906 to 1908, is a glorious Tang-period patchworked cloth found in Cave 17, now at the British Museum (fig. 5). The textile demonstrates the Chinese departure from the Vinaya-proscribed brown-coloured rags. Measuring 108 by 147 centimetres, the textile is composed of over forty luxurious and variously decorated silk fabrics, some resist-dyed, some brocaded, and some embroidered. Stein and the scholars Roderick Whitfield and Alan Kennedy have all done careful and thorough analysis of this extraordinary textile (Stein, 1921, pp. 1069–70; Kennedy, 1983, pp. 67–80; Whitfield, 1985, p. 3).

Patchwork attire for Chinese Buddhists have endured almost continuously (excepting periods of anti-Buddhist campaigns) to the present day. While maintaining the proscribed pattern of patches, the fabrics composing the robes were often far from the Buddha’s original concept of rags. Elegant examples incorporating luxurious silk brocades and embroideries are present in numerous museums around the world (fig. 6).

7

Daoist practitioner, early 20th century

Photographer and source unknown

8

Daoist practitioner, early 20th century

Photographer and source unknown

9

One Hundred Children in the Long Spring (detail)

Attributed to Su Hanchen (1101–61); Song dynasty (960–1279)

Ink and colour on silk; 30.6 x 521.9 cm (entire scroll)

National Palace Museum, Taipei

(After Wikimedia Commons, https://w.wiki/8yEw, accessed 26 January 2024)

Despite becoming emblematic of Buddhism in China, patchwork did not remain within the confines of Buddhist spaces. By the Ming period (1368–1644), at the latest, Daoists had also adopted the patchwork concept. When Sun Wukong, the monkey character in the Ming-era novel Journey to the West dresses up as a Daoist, in chapter 33, he wears what the author Wu Cheng’en (c. 1500–c. 1580) termed a bainayi, a word previously only used for Buddhist attire. Interestingly, in the previous chapter, the Buddhist monk Sanzang, speaking with a demon disguised as a Daoist, implies that the Daoist patchwork differed from the Buddhist design, saying, ‘I am a Buddhist priest and you are a Daoist. Although we wear different robes, we cultivate our conduct according to the same principles’ (translation by Anthony C. Yu, p. 468). In a Wanli period (1573–1620) edition of Journey to the West, an illustration depicts this demon, disguised as a Daoist, wearing a patchwork robe that is clearly distinct from the Buddhist jiasha. The difference between Buddhist and Daoist patchwork designs would continue.

Early and later 20th century photographs offer a sense of how Daoist patchwork robes diverged in design from Buddhist robes. The Daoist robes typically are devoid of regular patterning. A late 19th century or early 20th century unidentified photographer captured a Daoist practitioner dressed in a long patchwork robe composed of irregularly shaped and irregularly arranged fabrics. At a 1992 Daoist festival, in Xianyang, Shaanxi province, attended by this author, numerous Daoist practitioners wore patchworked jackets displaying a similar random appearance (figs 7–8).

10

Boy’s ‘one-hundred household’ robe (baijia pao) with central bagua symbol medallion

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 1850–1900

Silk embroidery, satin, and cotton; 65 x 114.6 cm

Art Institute of Chicago, Robert Allerton Endowment

Photo courtesy of Art Institute of Chicago

11

Boy’s robe

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Guangxu period (1875–1908)

Silk embroidered with silk and metallic threads; dimensions unknown

St. Louis Art Museum, Gift of Julius A. Gordon and Ilene Gordon Wittels in memory of Rose Gordon

Photo courtesy of St. Louis Art Museum

Beyond the Daoist robes, patchwork entered the secular world as a fashion during the late Ming and early Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. By the 17th century, women were wearing new styled robes, colloquially referred to as shuitianyi, a term clearly appropriated from the Buddhist context. (Rachel Silberstein has written an extensively researched, as yet unpublished, article on this subject, ‘Shuitianyi: Patchwork in Chinese Dress Culture’.) In paintings from the 17th and 18th century, women occasionally appear in these robes.

Intentionally patchwork-patterned clothes were already outside the monastic world by the late Song period (960–1279). Paintings from the late Song attest to the existence of patchworked clothes for children. The genre of ‘hundred children paintings’ (baizitu) arose as an auspicious image reflecting the aspiration for numerous male progeny. In baizitu, some children play while others imitate adult activities, such as painting, teaching, or being scholars. In a work attributed to Su Hanchen (1101–61) in the National Palace Museum, a group of children crowd around scrolls they have unrolled, as if they are scholarly gentleman (fig. 9). Off to the side is a younger child sporting a red, blue, white, and green patchworked jacket, each patch hexagonal in shape. Were these early displays of children wearing patchwork jackets meant to make them appear to be imitating Daoists or Buddhists? Textual resources still need to be searched to substantiate this supposition.

Children’s patchwork jackets came to be known as baijiayi, meaning ‘clothes of one hundred families’. To protect a young male child, baijiayi traditionally were created from fabric remnants gathered from each family in a village. Examples of baijiayi from the 19th and 20th centuries are still preserved in numerous public and private collections (figs 10–11), as are occasional photographs of children wearing them (fig. 12). The custom continues today, though it is far less common than even twenty years ago.

12

A Chinese boy standing next to a doorframe, wearing trousers and a variegated collar with a patchwork

By G.G. Johnson; c. 1900–20

California Historical Society Collection, University of Southern California Libraries Special Collections

Photo courtesy of University of Southern California

13

Child’s vest

By Huo Yingyang; late 1990s

Cotton; 43.2 x 35.6 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Joel Alvord and

Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

A late Qing period child’s jacket in the St. Louis Art Museum composed of hexagon-shaped embroidered silk fragments in the colours of yellow, purple, white, blue, red, and peach is strikingly similar in pattern to the child’s jacket in the Song painting attributed to Su Hanchen. Among the embroidered flower and butterfly decorations on the silk hexagons is a bagua symbol in its fully detailed form, with the eight trigrams surrounding a yin-yang design. The presence of this embroidery on the hexagon suggests that the hexagon shape, like the octagon, may have been intended to mimic the apotropaic bagua symbol. And the presence of the bagua symbol as a central panel on a silk patchworked child’s jacket in the Art Institute of Chicago suggests that these children’s jackets, like the bagua symbol, had taken on an apotropaic meaning in secular society.

The hexagon and octagon continue even today to be common patterns in baijiayi in Shaanxi province. This author has encountered, and acquired for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, several baijiayi from Xianyang, in Binzhou county, Shaanxi, with the bagua shape as a dominant visual pattern (fig. 13). The makers, in interviews, affirmed that they called the pattern bagua. Interestingly, this same bagua design was included on the jackets worn by the Daoists at the 1992 festival in Xianyang (described above). The commonalities between the Daoist jackets and the baijiayi supports a speculation that patchwork among the secular community might have arisen from contact with Daoist rather than Buddhist practitioners.

In the late 20th century, and still today, patchwork has been most visually apparent in rural China, hanging in doorways as door curtains (menlian) and as window curtains on the exterior of the home, to prevent drafts from entering the home in the winter months. Inside the home, patchwork textiles are filled with cotton as duvets covering heated platforms (kang) and as stool and bench cushion covers. And some mothers and grandmothers continue the tradition of making patchwork vests and jackets for their sons, as well as buttock covers for toddlers wearing split pants.

14

Zheng Yunyang demonstrating patchwork sewing, December 2019

Photo by the author

15

Couch cover

By Zheng Yunyang; 2019

Cotton; 83.8 x 210.8 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Unlike Buddhist adherents, the rural women making patchwork textiles are not obligated to adhere to a proscribed pattern. The results are a rich range of artistic expression, demonstrating an exciting yet, until now, rarely explored creativity among Chinese rural women. A review of the designs seen by this author over the past three decades shows that many makers begin with traditional patterns and then riff on them, like jazz musicians, creating personal and dynamic designs. Some stay closer to fixed patterns, and others avoid any consistent patterning, instead creating expressive, abstract compositions of colour and shape. Among the many patterns from which they work, and improvise, are: six-pointed stars, triangles, squares, and the bagua pattern. The same patterns appear in other Chinese decorative mediums, which may have inspired the patchwork makers.

The form of the bagua pattern is either a hexagon or octagon created from overlapping rhomboid strips. In a remarkably thorough 1949 publication recording window-lattice designs, A Grammar of Chinese Lattice, Daniel Sheets Dye discussed a hexagonal window with a pattern and construction remarkably close to the textile patchwork design.

Zheng Yunyang, a passionate patchwork maker, generously demonstrated the complex technique of making these patchwork octagons (fig. 14). Unlike most other patchworks, the construction necessitates both folding and sewing. Other women in the village noted that Zheng was the most skilled maker in their neighbourhood. From a quick glance at a bed cover (fig. 15), she may appear to be working within a set pattern, but a closer look reveals that she also enjoys improvising. The central designs of her octagons vary from five-pointed stars to crosses and occasional checkered designs. She also changes fabrics in unexpected places, here and there, adding random triangles and squares.

16

Door curtains using the six-pointed star pattern

a. By Xin Junying; Qingyang, Zhenyuan county, Gansu province; c. 2017; cotton; 106.7 x 198.1 cm

b. By Wang Jierong; Xianyang, Binzhou county, Shaanxi province; c. 2019; cotton; 121.9 x 203.2 cm

c. By Madame Li (1901–91); Qikou county, Shanxi province; 1980s; cotton; 185.4 x 82.6 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Another pattern, created from equilateral parallelograms of several colours arranged in specific orientations to one another, is often referred to by Chinese patchwork makers as a six-pointed star (fig. 16). For people raised with a strong sense of perspective, the pattern creates an optical illusion of cubes piled one upon another, but for many patchwork makers in China, the shape of the star is dominant in this composition. The ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as Renaissance designers, employed the pattern in floor tiles. And patchwork quiltmakers in the United States also took up the pattern, calling it ‘tumbling blocks’. Despite the identical nature of the construction, there is no evidence of cultural sharing between the American and Chinese patchwork artists. The pattern dates back in China to at least the Song period, where it is visible in architecture designs as window lattice and brick wall designs (fig. 17).

As with all patterns, patchwork makers take individual approaches in working with this configuration. Comparing the three door curtains in figure 16: The first artist remained consistent across the entire textile, using three different fabrics in uniform locational relationships to one another. The second artist linked all of the white diamonds, end to end, in lines angling from upper left to lower right; linked the grey and black diamonds in lines from upper right to lower right; and linked the red and pink diamonds horizontally across the space. Even with this general pattern, the artist occasionally wavered from her colour arrangements, creating an overall image that is more complex and dynamic.

17

Doorway, Qingyang county, Shanxi province, December 2019

Photo by the author

18

Bags of fabric triangles in the home of Li Jiyin (b. 1945), Baoji county, Shaanxi province, 2019

Photo by the author

The third artist went even further in deviating from any regularity. Most of the angled lines of diamonds are dark blue and green, resulting from the time of the Cultural Revolution, when most people wore only blue or green clothes. For the horizontally linked diamonds, the artist selected bright colours, often constructing individual diamond shapes from an assemblage of two, three, or four different colours. The three works in figure 16 together demonstrate a proclivity towards experimentation and the range of expression possible even within a limited composition.

Compositions created entirely from triangles are among the most common, as the simple three-sided shape allows for infinite variations.

A frequently employed pattern arranges eight or twelve triangles of fabric into a series of concentric squares decreasing in size, with a small square at the centre. Varying fabrics and sizes multiply the possible visual results (figs 19a–b). This interesting pattern appears repeatedly on painted ceilings in the Buddhist temple caves of Dunhuang, which seem to be imitating large patchworked canopies.

19a

Bedcover (detail)

Maker’s name unknown; Shandong province

Photo by author

19b

Bedcover (detail)

Maker’s name unknown; Shandong province

Photo by author

Aside from the several patterns discussed above, there are numerous other basic configurations that patchwork artists employ as foundations for their visual explorations. Some makers create works composed entirely of squares or rectangles. Others fashion their works from countless parallel thin strips. Many, like Zhu Fenglan’s bedcover in figure 20, combine several patterns together in a single work, producing ever-stimulating compositions. Still others dispose of any strict patterning and strike out on their own, randomly positioning irregular shapes into unique expressions.

One patchwork artist, Chen Yingping, created a small mat for her son in 1980 when he was an infant (fig. 21). She may have originally begun with a square made from pink and brown triangles (discernable just off the centre, in the figure) but then launched into creating an unexpected dance of bold shapes and colours. The square of triangles steadies the composition while the odd and off-kilter angles send a viewer’s eye on a circuitous journey, occasionally resting on the surprising, singular green shape at the far corner.

In the 1950s, Wang Yingying created a large bed cover by arranging mostly green and blue imperfect rectangles of varying hues, sizes, and shapes without regard to a grid or pattern (fig. 22). Towards the centre of the work, several larger fabric pieces steady the composition. And in the far corner, one red rectangle adds an extra dollop of visual animation to the work, tying together the entire composition.

20

Bedcover

By Zhu Fenglan; Shaanxi province, Binzhou County, 1980s

Cotton; 110.5 x 203.2 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

21

Child’s bed mat

By Chen Yingping (b. 1956); Shanxi province, Qikou county; 1980

Cotton; 168.9 x 78.7 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Joel Alvord and Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Among contemporary art historians and art lovers, these irregular compositions may kindle thoughts of mid-20th century abstract art. However, this ‘non-patterning’ has much earlier, pre-20th century precedents in Chinese visual culture. Crackle patterns in Song and Yuan (1272–1368) ceramics come to mind, as do cracked-ice-pattern window lattices. Perhaps even more relevant are the robes and jackets worn by Daoist disciples, who were still roaming the countryside in the late 20th century. The entry for the term na in a late Qing children’s vocabulary book (fig. 23) unmistakably shows a robe created from irregularly shaped and randomly placed fabrics stitched together. Since Buddhist monks’ patchwork jiasha are worn as mantles, rather than robes or jackets, the drawing seems to be illustrating a Daoist’s bainayi.

While the traditional Buddhist mantles reflect a disciplined regularity, the Daoist robes might have been the inspiration for freer self-expression. Thinking philosophically, these works recall the first sentence of the Dao De Jing: ‘The Way that can be told is not the absolute Way’ (Lin, 1948); or, ‘A way can be a guide but not a fixed path’ (as translated by Cleary, 1991). Just as the Confucian orderliness is fundamental to Chinese culture, the Daoist acceptance of veering from pattern is also deeply ingrained in Chinese culture.

22

Bed cover

By Wang Yingying, 1950s

Cotton; 188.6 x 149.9 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Joel Alvord and Lisa Schmid Alvord Fund

Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Notwithstanding these probable ancient origins and influences, artisans in rural China have taken patchwork to a new level—one might even say to a new art form. How do these objects fit into notions of Chinese art? For centuries, such village creations were not within the realm of artistic consideration. In the 20th century, with the rise of a respect for ‘the people’, writers, critics, and museum curators slotted these works into the category of folk art (minjian yishu). Many current international scholars are now advocating for the elimination of the term ‘folk art’ and for including all works of visual culture in the category of art. From this point of view, in many aspects, these works in fact resonate with art in traditionally established Chinese canons. For instance, like artists of calligraphy, patchwork makers are working entirely with abstract shapes with no pursuit of naturalism. And, like traditional literati artists, patchwork artists are not professionals. They do not sell their creations or work on commission; they make their works for their personal expression or to give to family or friends.

Notions of Chinese art grow and evolve, as they always have. Thus, as the practice of the patchwork art form is rapidly diminishing, it is time for greater explorations of its rich manifestations.

23

Detail showing the illustration for the term na in a late Qing children’s vocabulary book

By Liu Xinyuan (1848–1915); late 19th century

(After Fan Hui Shu [Instruction Book for Daily Life], vol. 8, p. 83, 1915 manuscript)

Nancy Berliner is Wu Tung Senior Curator of Chinese Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The author wishes to acknowledge gratitude to Alan Kennedy, Fei'er Ying, and Gillian Zhang for their gracious assistance in this research.

Selected bibliography

Thomas Cleary, The Essential Tao, New York, 1991.

Alan Kennedy, ‘Kesa: Its Sacred and Secular Aspects’, Textile Museum Journal 22 (1983): 67 –80.

Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of Laotse, New York, 1948.

Aurel Stein, Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China, Carried Out and Described Under the Orders of H. M. Indian Government, Vol. 11, London, 1921.

Roderick Whitfield, The Art of Central Asia: The Stein Collection in the British Museum, Tokyo, 1985.

Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew, Cave temples of Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road, Los Angeles, 2000.

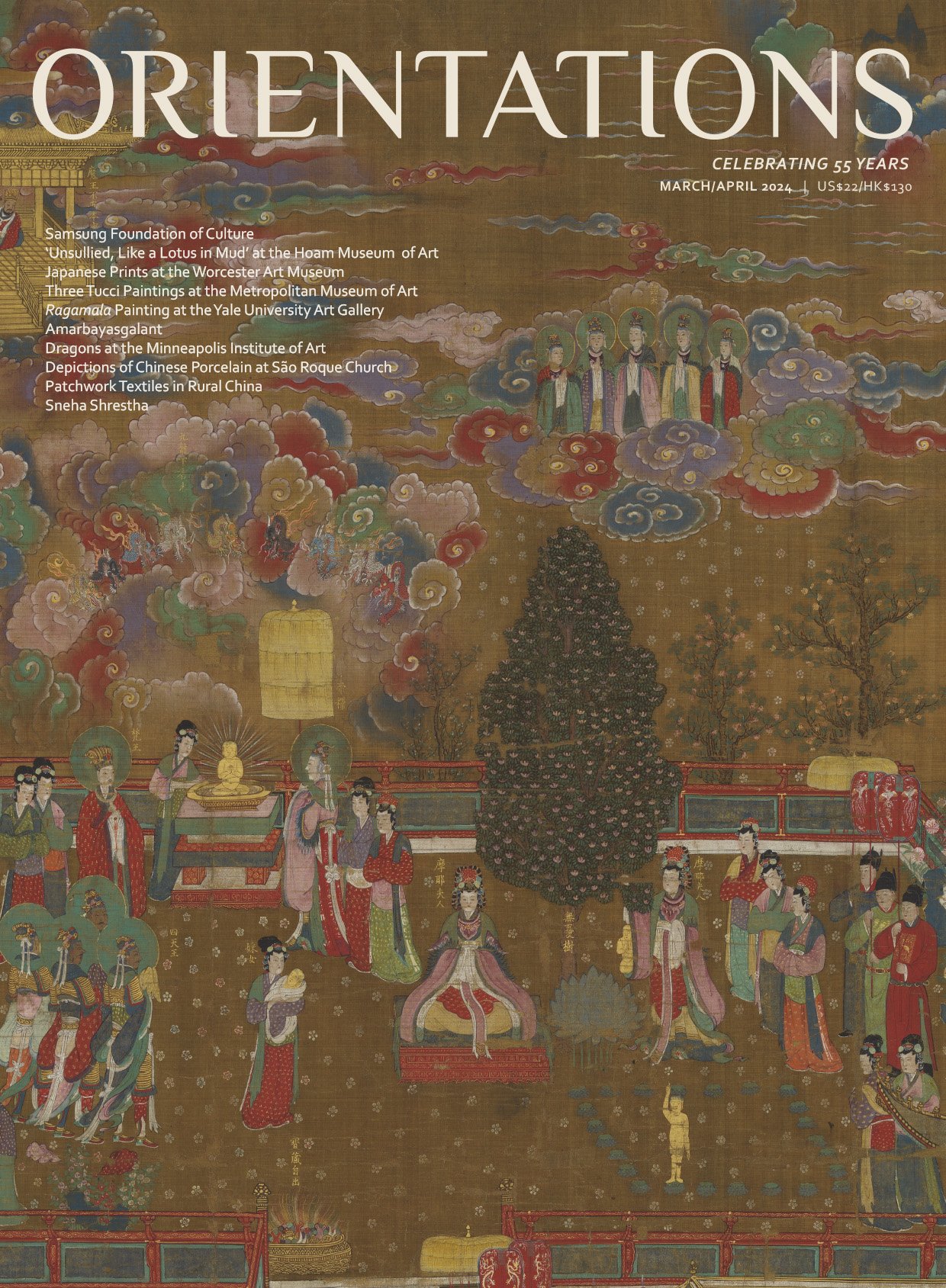

This article featured in our March/April 2024 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.