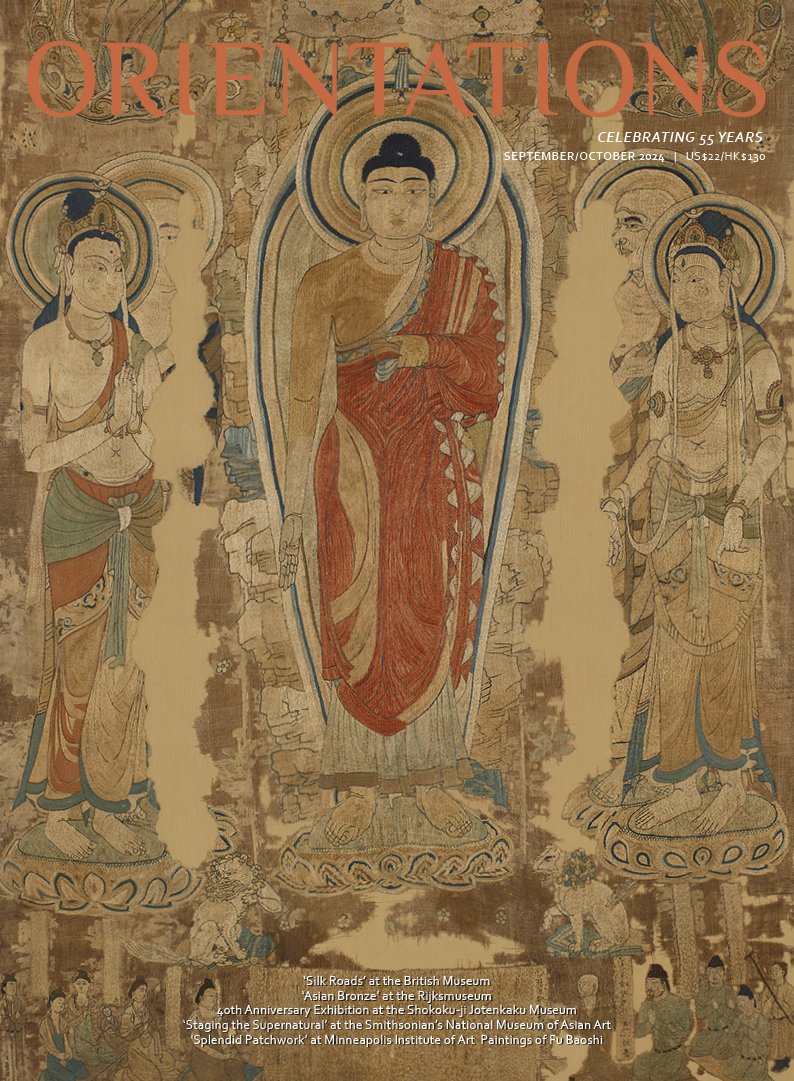

Splendid Patchwork: Buddhist Monastic Robes from Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) has cultivated a distinguished collection of Chinese art with notable strengths in several areas. Qing dynasty (1644–1911) silk textiles are represented with nearly one thousand works, comprising one of the largest and best collections in the West. The holdings include a large number of imperial robes, theatrical and military costumes, and unofficial attire. All categories of festive costumes and interior furnishings, including throne covers, are represented. The museum has also built one of the most noteworthy collections of Daoist and Buddhist ecclesiastical costumes in the country, composed of several dozen examples. A specific area of this fascinating collection, Buddhist priests’ robes from the Qing dynasty, is featured in the exhibition ‘Splendid Patchwork: Buddhist Monastic Robes’, on view from 4 May to 20 October 2024.

Known as kashaya, this type of robe, generally rectangular in shape, was worn over an inner garment and designed to be draped over the left shoulder, under the right arm, and fastened in the front with a clasp.

Each of these ritual garments is made up of small squares and depicts various Buddhist motifs. Many of these robes are ceremonial objects of Qing imperial origin, adorned with celestial landscapes that symbolize imperial court power. Together, they provide a rare opportunity to delve into an understudied subject, offering a glimpse into the origins, types, functions, and innovations of Buddhist monastic robes from India to China.

The Buddhist Vinaya texts (Daśa-bhāṇavāra-vinaya), which contain the rules and precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (communities), tell us that Buddha Shakyamuni began to consider robe design as a means of differentiating monks from heretics. On a cold night, Buddha conducted an experiment to find out the appropriate attire for keeping warm. He tested three robes during different periods of the night: early night, midnight, and late night. He realized that three garments were perfectly suited for protecting himself against the cold: the undergarment Antaravasaka, the upper robe Uttarasanga, and the outer robe Sanghati (T., juan 23, pp. 195 and 57).

1

Buddha

Gandhara (ancient region of Pakistan); c. 3rd century

Schist; 141.0 x 47.0 x 22.9 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund, in honor of Ruth and Bruce Dayton 2001.153

Following Buddha’s instructions, the venerable Ananda, his attendant and disciple, designed the robes by imitating the layout of rice paddies. He first processed fabric into strips of different lengths and then stitched these strips together into robes. The three robes were all composed of odd numbers of strips, representing the yang number, which symbolizes growth. This initial concept of robes based on rice paddies is known as futianyi (robe of paddies of blessing). It likens monks, who strive diligently to uphold their precepts, to fields of blessings for the world, allowing sentient beings to cultivate good fortune just as rice fields grow nourishing food. Further, robes made from discarded fabric pieces sewn together symbolize humility and the monk’s detachment from materialism and vanity (thus they are also known as bainayi, or ‘patchwork robe’).

The Buddha’s robes are the same as those of his monks, as depicted in the 3rd century Buddhist sculptures made in Gandharan region, though they are often more voluminous. The monks often wear only two of the garments, while the Buddha wears all three. In Indian Buddhist sculptures, two draping styles of the outer Sanghati robe are typically visible. One style (known as tongjian shi, or the shoulder-covering style in China) covers both shoulders, with the right corner of the robe wrapped around the neck and draped over the left shoulder (fig. 1). The other style (tanyoujian shi, or the right-shoulder-baring style) covers only the left shoulder, with the right corner of the robe wrapped under the right armpit and draped over the left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder exposed (Griswold, 1963, pp. 88-110).

In the centuries following Buddhism’s introduction to China, the representation of robes in art continued to adhere to the traditions seen in Indian prototypes, but there were some developments in draping styles, names, structures, and other aspects. The two styles described above remained popular in early Buddhist sculptures and paintings of the 5th and 6th centuries, but a third style, known as banpiantan shi (the right-shoulder-partially-baring style), evolved as well. It is exemplified in the famous Buddha image excavated in 460 CE from Cave 20 of the Yungang Grottoes in Datong, in which the Sanghati covers both shoulders from behind, but the right corner of the robe loops under the right armpit and is draped over the left shoulder, exposing the right chest and right arm. From the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) onwards, the most popular style in Chinese Buddhist art was slightly different, with the Sanghati covering both shoulders from behind and the right corner of the robe crossing the chest and abdomen to drape over the left elbow, rather than the left shoulder.

2a

Amoghasiddhi Buddha

China; Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Yongle period (1403–1424)

Lacquer and gold on sandalwood core; 19.5 x 14.4 x 9.5 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

99.178.4

2b

The reverse side of the Amoghasiddhi Buddha (fig. 2a)

Over the centuries, Buddhist robe Sinicization tended towards reducing body exposure while incorporating elements of Chinese design. Only the outer Sanghati retained the traditional rectangular shape worn to expose the right shoulder, but it was usually worn over a long-sleeved inner robe. During the late imperial period, statues with the right arm completely exposed were mainly seen in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, as exemplified by a lacquered wood statue of Amoghasiddhi Buddha in Mia’s collection (figs 2a–b). The distinctive patterns with infilled gold leaf indicate that it was a gift to a Tibetan monastery by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) Yongle Emperor (r. 1403–1424). More often, statues depicted the right corner of this robe fastened on the left shoulder rather than draped over it.

The kashayas in Mia’s collection vary in their decorative content, but all are cut as a horizontal rectangle or a gored variant. Most belonged to high-ranking abbots and senior priests and are more elaborate than those worn by typical Buddhist monks. Some contain imperial imagery, in which dragons cavort within celestial landscapes. It is likely that such robes, rich with court symbolism, were used in Buddhist ceremonies within the Forbidden City or at monasteries patronized by the court.

Qing rulers favored Buddhism, particularly the Tibetan or Lamaist form. The emperors sent tribute silk to major monasteries in Tibet and sponsored the construction of numerous stupas and temples throughout China. Buddhist shrines were also built within the Forbidden City as places of worship for the imperial family. During the Qianlong period (1736–1795), the number of Buddhist shrines inside and outside the imperial palace surged, with approximately forty chapels spread throughout the Forbidden City alone. The popularity of Buddhism also led to a tremendous demand for Buddhist robes. For the Qing court, these robes were not only essential items for Buddhist monasteries but also became special political tools for royal bestowals, rewards, and enhancing exchanges between the central government and ethnic people.

3

Formal court robe altered for Lamaist ritual dance

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century

Silk brocade and damask; 174 x 139.5 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.291

Based on Qing court archives and what we can observe in surviving robes, Buddhist robes encompassed a wide range of functions and styles. Three main types are most noticeable: robes for adorning Buddhist statues; robes used as offerings, which were displayed in Buddhist sanctuaries and were not meant to be worn; and robes for monks (particularly Lamas) to wear during significant Buddhist ceremonies (Ma Yunhua, “Qinggong jiucang” p. 111). One such robe, now in Mia’s collection, was probably made by the imperial workshop for a ceremonial Lama dancer (fig. 3). A set of ten similar robes is now held at the Palace Museum.

During the Qianlong period, the production of imperial Buddhist robes was mainly overseen by the Imperial Household Department and Jiangnan san zhizao (Three Imperial Manufactories in the Jiangnan Region). Before production, the Office of the Imperial Household would usually draft designs based on the emperor’s taste. After they were reviewed and approved by the emperor, the designs were sent to the Jiangnan san zhizao. Emperor Qianlong himself was personally involved in designing Buddhist robes. He mandated specific requirements for weaving techniques, styles, and materials, sparing no expense to ensure that the garments were luxurious and exquisite.

The current show at Mia offers a glimpse of the unique magnificence of such robes. One of the most elaborate examples is a richly colored satin shawl produced in the 18th century (fig. 4). The robe’s overt imperial imagery is auspicious in nature and immediately ties it to the Qing court. Each vertical border is embroidered with a front-facing five-clawed dragon under a magnificent canopy, ascending above a three-peaked mountain rising beyond sea waves. The border along the bottom of the robe features six dragons flying amid a celestial landscape. Below are surging waves from which stylized immortal islands rise. Scattered among the troughs of the waves are depictions of the eight Buddhist treasures (swastika, coral, etc.). The robe is visually dominated by a semicircular shoulder insert depicting a large dragon chasing a flaming pearl while flying among clouds, waves, and the eight Buddhist treasures. Interestingly, the central neck flap, somewhat trapezoidal in shape, is decorated with a single canopy, richly embroidered in multiple colours of thread and more ornate than the canopies on the vertical side borders. As it hangs over the top edge of the robe, it shrouds the head of the dragon.

4

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), early 18th century

Embroidered satin; 243.2 x 114.3 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.135

In the space within the borders and below the semicircular shoulder panel, there are eleven vertical panels with ivory satin borders. Six panels consist of alternating squares of gold dragons among clouds and peony blossoms with scrolling leaves. They alternate with another five panels containing single ascending or descending gold dragons in celestial landscapes. The motifs are all embroidered in couched, flat, and satin stitches with multicoloured silk floss and gold metal-wrapped thread against a yellow satin ground. The dragons are the most impressive, their bodies embroidered with vivid, textured scales in gold thread. They are almost sculptural, as though depicted in relief; the extraordinary three-dimensional quality of the embroidery creates an illusion of layers and depth. Their spines, spiky tails, claws, horns, moustaches, fangs, and pupils are all embroidered with white thread. Portions of the edge of each leg are highlighted with red. Such designs, reflecting conventions of Qing court dress, demonstrate that kashayas had evolved from functional monastic clothing developed in India into Sinicized robes that communicated imperial power.

Another fine example, also from the Qianlong period, is a kashaya made of blue silk tapestry—kesi— with an orange silk tabby (fig. 5). The decorative scheme is nearly identical to the previous example. The top half features the same large half-ovoid shoulder panel decorated with a dragon bearing the same expression and posture. Both sides of the top border are decorated with the same number of bats as the yellow robe: five on the left side and three on the right. The top of each vertical side border features a canopy, similarly decorated with stylized dragons holding tassels of pearls. Below each canopy is a vertical dragon in the same formation as those on the previous robe. The bottom border is nearly identical as well. The space within the borders features a patchwork layout with the same number of columns, and the designs within them are almost identical to those in the other robe as well, aside from their slightly varying colours and the different technique and material used to produce them. The main differences include the absence of the neck flap at the centre of the top edge; the deep blue background, rather than golden yellow; and the motifs formed from woven kesi silk rather than embroidered. The imagery also indicates that this robe appears to be a ceremonial object of imperial sponsorship meant for high-ranking abbots of a court temple.

Another kashaya at Mia (fig. 6) is identical to the previous example, aside from the inclusion of a neck flap depicting a Buddhist canopy, serving the same function as the one on the yellow satin kashaya (see fig. 4). Made of blue silk tapestry kesi, it is patterned with multicoloured plied-cord silk and gold metal-wrapped thread. The striking similarities between these robes suggest that they were probably produced in the same imperial workshop at the same time. However, the presence of a red ink seal on the blue robe with the neck flap (fig. 6a) raises a question: were all kashayas worn by Buddhist priests, or could they have served different purposes? Although the seal is partially illegible, it is comparable to similar ones on robes in the Palace Museum collection (Zhang Shuxian, 2008, pl. 2). It appears to read 升平署圖記 Shenpingshu tuji (Record of the Office of Peace and Prosperity). The Shengpingshu was a bureau in the Qing palace responsible for overseeing opera affairs. Many Qing imperial theatrical costumes, including those Buddhist priest robes now housed in the Palace Museum, originated from this institution and feature its distinctive seal. This suggests that some robes of this type were not actually religious garments but theatrical costumes.

5

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), early 18th century

Silk tapestry (kesi) ; 300.4 x 114.0 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 41.74.8

Opera was an indispensable part of royal life in the inner court of the Qing dynasty. Most Qing rulers, particularly Emperor Qianlong and Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), enjoyed watching performances, reading scripts, directing rehearsals, or playing musical instruments. Theatrical activities fell into two categories: Yueling Chengying 月令承 應 involved performances coinciding with festivals such as New Year’s Day, the winter solstice, the beginning of spring, and the Bathing of the Buddha, while Qingdian Chengying 慶典承應 consisted of performances on auspicious occasions like the emperor’s birthday, royal weddings, and days of celebration for victories or imperial tours. To manage the frequent performances in the palace by internal and external opera troupes, a special bureau called the Nanfu 南府 (the South Office) was established during the Kangxi period (1662–1722), which Emperor Daoguang (r. 1821–1850) later replaced with the Shenpingshu in 1827. In addition to the opera troupe composed of eunuchs (called Neixue 內學 ), which performed inside the palace, there were also troupes from outside the palace that exclusively served the court (Waixue 外學 ).

As an essential component of opera performances, costumes rapidly developed during these periods. Based on their collection, researchers at the Palace Museum in Beijing determined that the finest costumes were produced under the Nanfu. Crafted from exquisite materials, they were all produced in the Three Imperial Manufactories in the Jiangnan Region, each utilizing their own technological advantages. Examples include Jiangning’s gold-threaded brocades and Japanese satins; Suzhou’s kesi silk tapestry, embroidery, and brocades; and Hangzhou’s silk gauzes and satins. Their garments were masterfully executed, featuring innovative and unique patterns. Afterwards, from the reigns of Emperors Daoguang to Guangxu (1875–1908), court theatrical activities were overseen by the Shengpingshu. While it produced higher quantities of costumes, the robes it produced rarely matched the standards for material and craftsmanship held under the Nanfu (Zhang, ‘Qinggong yanxi qingkuang’, p. 8).

Many costumes in the Palace Museum’s collection have red ink seals or marks written in black ink on the lining. They either indicate the performance venue (such as 長春 Changchun and 重華宮 Chonghua Palace in the Forbidden City, and 同樂園 Tongle Garden and 含淳堂 Hanchun Hall at the Yuanmingyuan Summer Palace); names of specific operas (such as 目連 Mu Lian, 昭代 Zhaodai, and 螽斯衍慶 Zhongsi yanqing); names of specific court opera troupes (including troupes within the Qing palace, such as 南府頭學 Southern Academy Head School, 景中學 Jingzhong School, and 景山大班 Jingshan Major Troupe; and external court troupes such as 南府外頭學 Southern Academy outside the Palace and 外三學 Outer Third School); and names of nongovernmental opera troupes who performed in the palace wearing designated court-produced costumes marked with specific seals (such as 同春 Tongchun, 仁合 Renhe, 永吉 Yongji, and 吉祥 Jixiang) (Zhang, ‘Qinggong yanxi qingkuang’, pp. 8–9). Such inscriptions provide specific information to date the robes and their origins, offering clear evidence that many kashayas were actually theatrical costumes.

6

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), early 18th century

Silk tapestry (kesi) ; 242.6 x 114.6 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.134

6a

Detail of the robe in fig. 6, showing a red ink seal on the lining

It is important to note that some costumes produced under the Nanfu continued to be used during the Shengpingshu period, so they may bear seals from the later period. In fact, some costume linings are marked with multiple seals from different periods. Given this information, the kesi robe (see fig. 6a) discussed earlier appears to date to the Qianlong period, despite the Shengpingshu seal on its lining that would otherwise indicate a later date.

Despite its lack of imperial imagery, another kashaya in Mia’s collection (fig. 7) can be identified as a theatrical robe produced by the Qianlong imperial workshop, based on its exquisite material and craftsmanship and the fact that there is a nearly identical example in the Palace Museum’s collection that researchers have identified as opera attire (Zhang, 2008, pl. 111). The robe is bordered by lotus scrolls of multicoloured plied-cord silk and gold metal-wrapped thread against a yellow ground. The space within the borders is divided into six gridded columns that alternate with five narrow vertical columns, each depicting four stylized dragons. The panels comprising the gridded columns are not in a consistent pattern and do not have a symmetrical layout, which creates a handmade patchwork-like effect. Large, brightly coloured panels, each depicting a different Buddhist motif against a colourful background, alternate with shorter horizontal panels depicting stylized dragons against a yellow background. Motifs in the large panels include the dragon, phoenix, white elephant, lion, white horse, offerings in bronze vessels, zithers, ruyi sceptres, and Buddhist treasures such as the lotus flower, carp fish, canopy, and coral.

This type of robe seems to have been very popular at the time, as there are several similar robes in other North American collections. Their shapes cover three types: straight rectangles (Mia, RISD Museum, Brooklyn Museum), rectangles with pleats on one side (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art), and rectangles with a slightly upturned right side (Art Institute of Chicago, University of Alberta Museum). At least four robes (Mia, Metropolitan Museum of Art, University of Alberta Museum, RISD Museum) have pink linings without seals or inscriptions (the others are unknown).

7

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century

Silk tapestry (kesi) ; 205.1 x 106.4 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.132

8

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), late 18th century

Embroidered satin; 213.4 x 108.3 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.287

Another kashaya featuring a design with clear Qing imperial connotations is a full-length shawl of embroidered satin (fig. 8). The robe is rectangular but angles upwards on the right side, forming an irregular shape. The four edges of the robe depict dragons, some soaring among lingzhi fungus-shaped clouds and bats and others above stylized sea waves in which the eight Buddhist treasures are scattered. The space within the borders is divided into seven gridded columns, each consisting of five rectangular panels in two sizes and multiple colours. Each panel has its own unique design. The larger panels depict blossoms intertwined with different treasures, such as a fly whisk, a cane with a handle shaped as an animal head, a set of books, a flower, a bucket, a chain of pearls, a vajra, a pagoda, a lantern, a lion, a tiger, a ruyi sceptre, a ladle, a flowerpot, and so on. The top and bottom squares of the left- and rightmost columns each feature a smaller rectangular area in one corner that depicts a Buddhist treasure: a sword, a pipa, a canopy, and a dragon amid flames. The gridded columns alternate with vertical panels of the same height that depict vertical dragons.

This kashaya bears the same stylistic and technical details seen on the 18th century robes discussed above. For instance, the spines, nails, moustaches, and teeth of the dragons are all embroidered with white thread, while their main bodies are embroidered with gold thread, giving them a sculptural, relief-like quality. The dragons’ legs are embroidered on one side with red thread, indicating a reflection from the flaming pearl nearby. However, from craftsmanship perspective, this robe does not compare to the exquisite examples made in the earlier period. Although all the dragons are embroidered with gold metal-wrapped thread against a blue satin ground, the couched stitches are quite loose. It therefore seems likely that the robe was produced later, in the 19th century. Although it has no inscription, its comparatively low quality suggests that it served as a theatrical costume. A small wedge-shaped decoration with a parcel-like motif is sewn diagonally at the top centre, seemingly a symbolic nod to the moveable neck flaps like the one on the previous example.

Another kashaya from Mia’s collection appears to be a theatrical robe of silk brocade from the same period (fig. 9). It consists of patchwork rectangles of alternating brocades in multicoloured silk and gold metal-wrapped thread decorated with cloud scrolls, Buddhist treasures, and dragon roundels. The borders and intervening bands depict tendrils and shou (longevity) medallions. On the red silk lining behind the upper right corner is a trapezoidal patch with a piece of pink silk ribbon sewn in for tying the robe (fig. 9a). Like the previous example, this robe also has a diagonally placed trapezoidal decoration at the top centre instead of a neck flap.

9

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 18th century

Silk brocade; 240.7 x 117.2 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.129

9a

Detail of the robe in fig. 9a, showing a trapezoidal patch with a piece of pink silk ribbon sewn onto the red silk lining

The kashayas discussed above seem to have been produced by royal workshops, based on their exquisite materials and craftsmanship and, on the first examples, the imperial imagery. While some may have been worn by senior monks during religious ceremonies in Buddhist temples, most seem to have been costumes worn by opera troupes while performing for the royal family.

Mia’s collection also includes some kashayas that feature purely Buddhist or folk designs without imperial motifs like dragons or phoenixes. These kashayas are lower quality than those discussed above and probably belonged to non-imperial Buddhist temples, to be worn by high-ranking monks during rituals. One such example is a rectangular shawl made of embroidered satin (fig. 10). It is composed of three pieces of white silk sewn together. The main register of the robe is divided into a grid with gold metal-wrapped threads, creating a patchwork-like pattern. Each square within the grid is adorned with a figure or motif in multicoloured silk. The Buddhist figures adorning the robe are arranged to create a hidden pyramid shape, with the Buddha at the centre top and a heavenly king directly below. Symmetrically arranged bodhisattvas and other celestial figures, holding various objects, face towards the Buddha within the pyramid. The patches beyond the lines of the central pyramid depict monks. Buddhist treasures are illustrated in small patches on the top and bottom rows. The four borders are adorned with the Eighteen Luohans or arhats (enlightened saintly men), along with a seated Buddha at the centre top and a guardian king at the top of the left border.

All figures and other motifs are embroidered with multicoloured silk on a white ground. Pearls and coral beads have been incorporated into the design of the figures within the pyramid. The Buddha figure, for instance, stands on a lotus throne, with scrolling branches below that merge into a cloud pattern surrounding the entire figure. While the body and robes of the figure are embroidered with thread, his curling hair and topknot are adorned with tiny pearls. The pearls also decorate the lotus flower–shaped bowl in his left hand. On the back, in the top right corner, a jade ring is used to fasten the robe (fig. 10a).

10

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century

Embroidered satin; 276.4 x 128.9 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.240

10a

Details of the robe in fig. 10, showing a jade ring sewn at the upper back

Another robe at Mia apparently derives its iconography from the Thousand Buddha theme (fig. 11). Mahayana Buddhism asserts that there are countless Buddhas. Contemplating and reciting the names of the thousand Buddhas can produce miraculous effects, ultimately helping one to step into the realm of Buddhahood. The theme became a common motif in the Buddhist art of various regions, seen widely in caves, stelae, pagodas, and paintings. It reached a peak in the 6th century in Northern China, and its influence continued into the Qing dynasty. The main register of this robe is composed of one hundred staggered rectangular panels surrounded by four borders depicting a continuous lotus scroll pattern. Most of the panels contain an image of the Buddha in alternating poses of contemplation on a lotus pedestal. The panels along the top and bottom of the grid alternate with smaller squares depicting lotus pedestals. Interestingly, a jade hook in the shape of a dragon is sewn at the upper front of the robe for fastening.

Some patterns on kashayas also reflect the infiltration of secular culture and even Daoist ideas into Buddhist art at that time. Inextricably linked with popular culture, Daoism was the most dynamic and influential religion in the art of late imperial China. A rectangular shawl in Mia’s collection perfectly exemplifies this (figs 12a-b). Crafted from embroidered silk damask, it features borders adorned with a pattern of gold lotus flowers connected by meandering scrolls. At the centre of the top border, a pentagonal patch evokes the neck flaps seen on kashaya of the 18th century. On the red silk lining behind the upper right corner, there is a double-diamond–shaped patch with a loop for tying the robe (fig. 12c). Within the borders are 25 vertical columns of patches in couched gold metal-wrapped thread depicting motifs associated with Daoist concepts of longevity and immortality: a bat, a shou character, and a recumbent deer with its head turned back, holding a branch of lingzhi fungus in its mouth. The Lingzhi fungus represents the elixir of the immortals in Daoist legends, and deer represent their mounts; in popular culture of the time, the deer also alluded to wealth. Each column is composed of four long vertical patches and one smaller patch at the top or bottom, with the arrangement alternating across the grid. The top patch of the centre column depicts a seated Buddha, embroidered with multicoloured silk floss.

11

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century

Embroidered satin; 288.9 x 127.6 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.261

As discussed above, Mia’s collection provides a glimpse at the types, functions, and popular styles of kashayas during different periods of the Qing dynasty, as well as their materials and techniques. Within this group of works, Qing dynasty kashayas, regardless of fabric and weaving techniques, generally fall into three styles: rectangular, rectangular with a cluster of pleats on the right side, and rectangular with the right side angled upwards. The lining of the robe typically has a sewn pocket on the upper right side—sometimes attached to a single tie, sometimes to a ring or hook—used to connect the two ends of the robe when worn. The most exquisitely made and finely crafted Qing dynasty kashayas are those with dragon patterns and other symbols of royal authority. These robes were either used by high-ranking monks from temples sponsored by the royal family during religious ceremonies or served as costumes for the court opera troupes that performed for the royal family. The seals and inscriptions found on the linings provide effective clues for determining their date and function. It can be inferred that a significant portion of existing kashayas made by the court workshops were likely theatrical costumes. Conversely, some robes with more diverse patterns that seem unrelated to the royal family might have belonged to monks from various temples. Although Buddhist motifs are dominant, one can also see the influences of Daoism and secular culture.

Undoubtedly, these robes associated with the Qing court, whether worn by high monks in royal temples or as costume in performances, are the most striking. These robes reflect the complex imperial influences on the monastic garment and showcase exceptional artistry. Although they retain the basic shape of traditional Buddhist robes, their decorative scheme, similar to those on imperial dragon robes, add a political dimension to their original religious significance, becoming symbols of Qing imperial power. The meticulous craftsmanship of the royal workshops further enhances the expression of the fusion between religious and imperial authority.

12a–b

Buddhist priest’s robe (kashaya)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century

Embroidered silk brocade; 235.6 x 122.6 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art; The John R. Van Derlip Fund 42.8.286

Detail of fig 12a

12c

Detail of the robe in figs. 12a–b, showing a double-diamond–shaped patch with a loop on the red silk lining for tying the robe

Liu Yang is chair of Asian Art and curator of Chinese art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance received from Coco Banks and Eve Liu in the preparation of this essay.

Selected bibliography

Chen Yuexin, ‘Foyi yu sengyi gainian kaobian’ [An examination of the concepts of Buddha’s robes and monastic garments], Palace Museum Journal 2 (2009): 48–72.

Griswold, A. B., ‘Prolegomena to the Study of the Buddha’s Dress in Chinese Sculpture: With Particular Reference to the Rietberg Museum’s Collection’, Artibus Asiae 26, no. 2 (1963): 85–131.

Ma Yunhua, ‘Qianlong shiqi qinggong foyi de zhizuo yu guanli’ [The making of Buddhist robes in the Qing palace during the Qianlong period], Journal of Gugong Studies 7 (2022): 361–71.

Ma Yunhua, ‘Qinggong jiucang foyi kao’ [A study of Buddhist robes from the Qing palace collection], Palace Museum Journal 5 (2022): 111–21.

T., J. Takakusa and K. Watanabe, eds., Taisho shinshu daizokyo, Tokyo, 1927.

Zhang Shuxian, ed., Qinggong xiqu wenwu [Opera attire of the Qing dynasty palace], Shanghai, 2008.

Zhang Shuxian, ‘Qinggong yanxi qingkuang yu xiangguan wenwu’ [Opera performances in the Qing palace and related theatrical attire], in Zhang Shuxian, ed., Qinggong xiqu wenwu, Shanghai, 2008.

This article featured in our September/October 2024 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.